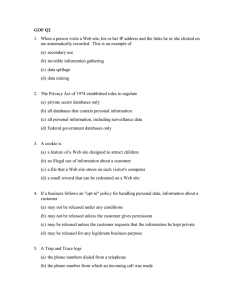

Surveillance Law Through Cyberlaw`s Lens

advertisement