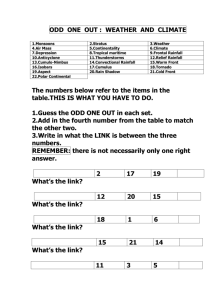

Atmospheric circulation patterns, cloud-to-ground lightning

advertisement