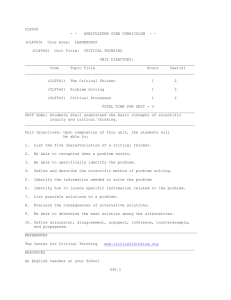

The 33rd Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and

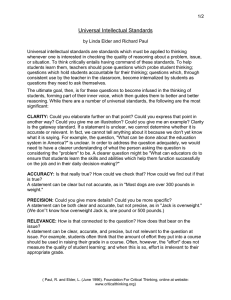

advertisement