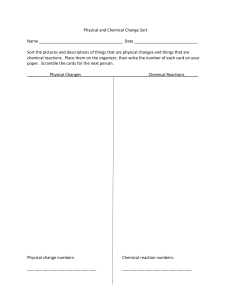

I III II IV V - Exploratorium

advertisement