parent as home teacher of suzuki cello, violin, and piano students

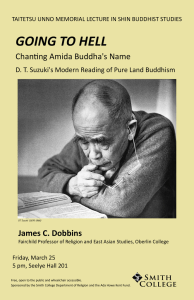

advertisement