our website - TEAM-TN

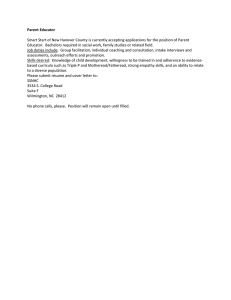

advertisement