Halting the Race to the Bottom

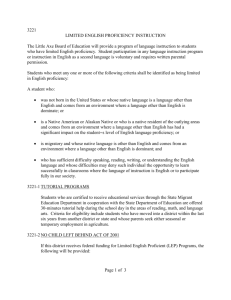

advertisement