Electromagnetic Induction

advertisement

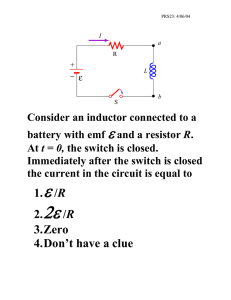

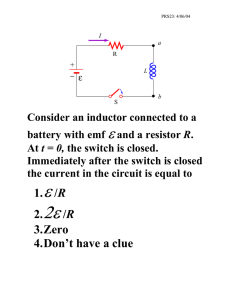

Electromagnetic Induction! March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 1 Faraday’s Law of Induction ! The magnitude of the potential difference, ΔVind, induced in a conducting loop is equal to the time rate of change of the magnetic flux through the loop. ΔVind = − dΦ B dt ! We can change the magnetic flux in several ways: dB A,θ constant: ΔVind = −Acosθ dt dA B,θ constant: ΔVind = −Bcosθ dt A, B constant: ΔVind = ω ABsinθ ! Where A is the area of the loop, B is the magnetic field strength, and θ is the angle between the surface normal and the B field vector March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 2 Lenz’s Law - Four Cases ! (a) An increasing magnetic field pointing to the right induces a current that creates a magnetic field to the left ! (b) An increasing magnetic field pointing to the left induces a current that creates a magnetic field to the right ! (c) A decreasing magnetic field pointing to the right induces a current that creates a magnetic field to the right ! (d) A decreasing magnetic field pointing to the left induces a current that creates a magnetic field to the left March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 3 Self Induction ! Consider a circuit with current flowing through an inductor that increases with time ! The self-induced potential difference will oppose the increase in current ! Consider a circuit with current flowing through an inductor that is decreasing with time ! A self-induced potential difference will oppose the decrease in current ! We have assumed that these inductors are ideal inductors; that is, they have no resistance ! Induced potential differences manifest themselves across the connections of the inductor March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 5 Mutual Induction ! Consider two adjacent coils with their central axes aligned March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 6 Mutual Induction ! The mutual inductance of coil 2 due to coil 1 is N 2 Φ1→2 M1→2 = i1 ! Multiplying both sides by i1 gives i1 M1→2 = N 2 Φ1→2 ! If i1 changes with time we can write di1 dΦ1→2 M1→2 = N2 dt dt ! Comparing with Faraday’s Law gives us di1 ΔVind,2 = −M1→2 dt ! A changing current in coil 1 produces a potential difference in coil 2 March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 7 Mutual Induction ! Now reverse the roles of the two coils March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 8 Mutual Induction ! Using the same analysis we find di2 ΔVind,1 = −M 2→1 dt ! If we switched the indices 1 and 2 and repeated the entire analysis of the coils’ effects on each other, we could show that M1→2 = M 2→1 = M ⇒ di2 di1 ΔVind,1 = −M ΔVind,2 = −M dt dt ! Here M is the mutual inductance between the two coils ! One major application of mutual inductance is in transformers March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 9 RL Circuits ! We know that if we place a source of external voltage, Vemf, into a single loop circuit containing a resistor R and a capacitor C, the charge q on the capacitor builds up over time as q = CVemf (1− e −t/τ RC ) τ RC = RC ! The same time constant governs the decrease of the initial charge q0 in the circuit if the emf is suddenly removed and the circuit is short-circuited q = q0e −t/τ RC ! If a source of emf is placed in a single-loop circuit containing a resistor with resistance R and an inductor with inductance L, called an RL circuit, a similar phenomenon occurs March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 10 RL Circuits ! Consider a circuit in which a source of emf is connected to a resistor and an inductor in series ! If the circuit included only the resistor, the current would increase quickly to the value given by Ohm’s Law when the switch was closed ! However, in the circuit with both the resistor and the inductor, the increasing current flowing through the inductor creates a self-induced potential difference that opposes the increase in current ! After a long time, the current becomes steady at the value Vemf/R March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 11 RL Circuits ! Use Kirchhoff’s loop rule to analyze this circuit assuming that the current i at any given time is flowing through the circuit in a counterclockwise direction ! The emf source represents a gain in potential, +Vemf, and the resistor represents a drop in potential, -iR ! The self-inductance of the inductor represents a drop in potential because it is opposing the increase in current ! The drop in potential due to the inductor is proportional to the time rate change of the current and is given by ΔVind = −L March 13, 2014 di dt Chapter 29 12 RL Circuits ! Thus we can write the sum of the potential drops around the circuit loop as Vemf di − iR − L = 0 dt ! Rewrite this equation as di L + iR = Vemf dt (differential equation for current) ! The solution is Vemf Vemf L −t/τ RL −t/( L/R ) i(t) = 1− e = 1− e τ RL = ( ) R R R ( March 13, 2014 ) Chapter 29 13 RL Circuits ! Now consider the case in which an emf source had been connected to the circuit and is suddenly removed ! We can use our previous equation with Vemf = 0 to describe the time dependence of this circuit di di VL +VR = L + iR = 0 ⇒ L + iR = 0 dt dt March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 14 RL Circuits ! The solution to this differential equation is i(t) = i0e −t/τ RL where the initial conditions when the emf was connected can be used to determine the initial current, i0 = Vemf /R ! The current drops with time exponentially with a time constant τRL = L / R ! After a long time the current in the circuit is zero March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 15 Energy of a Magnetic Field ! We can think of an inductor as a device that can store energy in a magnetic field in the manner similar to the way we think of a capacitor as a device that can store energy in an electric field ! The energy stored in the electric field of a capacitor is 1 q2 UE = 2C ! Consider the situation in which an inductor is connected to a source of emf ! The current begins to flow through the inductor producing a self-induced potential difference opposing the increase in current March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 18 Energy of a Magnetic Field ! The instantaneous power provided by the emf source is the product of the current and voltage in the circuit assuming that the inductor has no resistance di di + i ( 0 ) = Vemf = L dt dt ⎛ di ⎞ P = Vemf i = ⎜ L ⎟ i ⎝ dt ⎠ L ! Integrating this power over the time it takes to reach a final current yields the energy stored in the magnetic field of the inductor 1 2 U B = ∫ P dt = ∫ Li ′ di ′ = Li 0 0 2 t i ! The energy stored in the magnetic field of a solenoid is 2 1 1 1 N U B = Lsolenoidi 2 = µ0n 2 Ai 2 = µ0 Ai 2 2 2 2 March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 19 Energy density of a Magnetic Field ! The magnetic field occupies the volume enclosed by the solenoid ! Thus, the energy density of the magnetic field of the solenoid is 1 2 2 µ n Ai 0 UB 1 2 uB = = = µ0n 2i 2 volume A 2 ! Since B = μ0ni, we can write 1 2 uB = B 2 µ0 ! Although we derived this using an ideal solenoid, it is valid for magnetic fields in general March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 20 Work Done by a Battery ! A series circuit contains a battery that supplies Vemf = 40.0 V, an inductor with L = 2.20 H, a resistor with R = 160.0 Ω, and a switch, connected as shown PROBLEM ! The switch is closed at time t = 0 ! How much work is done between t = 0 and t = 0.0165 s? SOLUTION THINK ! When the switch is closed, current begins to flow and power is provided by the battery ! Power is the voltage times the current at any given time ! Work is the integral of the power over time March 13, 2014 Physics for Scientists & Engineers, Chapter 22 21 Work Done by a Battery SKETCH ! The sketch shows the current as a function of time RESEARCH ! The power in the circuit at any time t after the switch is closed is P (t ) = Vemf i (t ) ! The current as a function of time for this circuit is Vemf −t/τ RL i (t ) = 1− e τ RL = L / R ( ) R March 13, 2014 Physics for Scientists & Engineers, Chapter 22 22 Work Done by a Battery ! The work done by the battery is the integral of the power over the time T in which the circuit has been in operation T W = ∫ P (t ) dt 0 SIMPLIFY ! Substituting and rearranging gives us W=∫ T 0 2 Vemf 1− e −t/τ RL ) dt ( R ! Which evaluates to 2 Vemf W= R 2 Vemf W= R March 13, 2014 ⎡⎣t + τ RL e −t/τ RL T ⎤⎦0 ⎡⎣T + τ RL ( e −T /τ RL −1) ⎤⎦ Physics for Scientists & Engineers, Chapter 22 23 Work Done by a Battery CALCULATE ! First we calculate the time constant τRL = L / R = ( 2.20 H ) / (160.0 Ω ) = 1.375⋅10−2 s ! Now the work 2 40.0 V ) ⎡ ( W= 0.0165 s + 160.0 Ω ⎣ (1.375⋅10 s)(e −2 −0.0165 s/1.375⋅10−2 s ) −1 ⎤ = 0.06891 J ⎦ ROUND ! We round our result to three significant figures W = 0.0689 J DOUBLE-CHECK ! To double-check, let’s assume that the current in the circuit is constant in time and equal to half of the final current March 13, 2014 Physics for Scientists & Engineers, Chapter 22 24 Work Done by a Battery ! The average current if the current increased linearly with time is 1 1 Vemf iave = i (T ) = 1− e −T /τ RL ) ( 2 2 R 1 40.0 V −0.0165 s/1.375⋅10−2 s iave = 1− e = 0.0874 A 2 160.0 Ω ( ) ! The work would then be W = PT = iaveVemf T = ( 0.0874 A )( 40.0 V )( 0.0165 s ) = 0.0577 J ! This is less than, but close to, our calculated result ! We are confident in our answer March 13, 2014 Physics for Scientists & Engineers, Chapter 22 25 Modern Applications ! Computer hard drives, videotapes, audio tapes, magnetic strips on credit cards ! Storage of the information is accomplished by using an electromagnet in the “write-head” ! A current that varies in time is sent to the electromagnet and creates a magnetic field that magnetizes the ferromagnetic coding of the storage medium as it passes by ! Retrieval of the information reverses the process of storage ! As the storage medium passes by the “read head”, the magnetization causes a change of the magnetic field inside the coil ! This change of the magnetic field induces a current in the read head which is then processed March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 26 ! Higher storage density! ! Computer hard drives over 250 GB ! Giant magnetoresistance March 13, 2014 Chapter 29 27