Higher Education and Student Aspirations

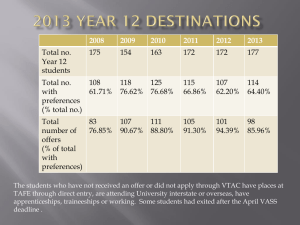

advertisement