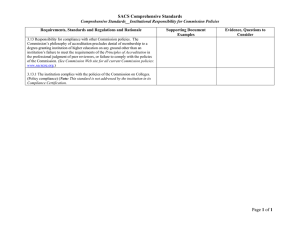

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

advertisement