STUDENT TEACHERS` EXPERIENCES OF CIRCLE

advertisement

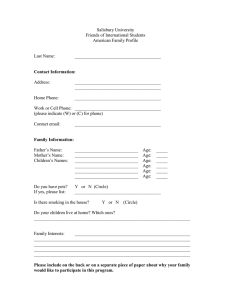

STUDENT TEACHERS’ EXPERIENCES OF CIRCLE TIME: IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE Dr. Bernie Collins Dr. Anne Marie Kavanagh St. Patrick’s College of Education Dublin City University This report is funded by the DICE Project. 1 Acknowledgements The impetus for the research outlined in this report arose out of conversations with student teachers about their experience of SPHE, and circle time in particular, prior to coming to college for teacher education. It appeared that, for some students at least, the reality did not match the promise held out of an empowering and esteeming circle. Conscious of a dearth of research in the Irish context, we decided to design and conduct research which could investigate circle time’s potential at a personal, social and wider world level. We are indebted to the following for their assistance on this research journey: The Development and Intercultural Education project (DICE) for agreeing that this was an important area of research and funding it accordingly The students who took part in the study from both colleges – their honest responses allowed us to gain a much better picture of the reality of circle time for students at both primary and post-primary level in Ireland Dr. Carol O’Sullivan who facilitated the research with students in Mary Immaculate College of Education The research committees in St. Patrick’s and Mary Immaculate Colleges of Education who gave us guidance and approval to undertake the work We hope that the education community in Ireland and further afield will find this report a useful and thought-provoking addition to the literature on circle time. Dr. Bernie Collins Dr. Anne Marie Kavanagh September 2013 2 List of Figures Figure 1: Methodological Framework Figure 2: Circle Time Experiences Stratified by Class/Year in Primary/Post-Primary School Figure 3: Themes Explored During Circle Time Sessions in Primary/Post-Primary School Figure 4: Effective Circle Time Sessions: Teacher Skills Figure 5: Use of Circle Time in Own Future Teaching 3 Chapter One: Introduction 1.1 Introduction Schools are conceptualised as key sites for fostering personal and social skills development, tackling insidious social problems such as racism, and cultivating the development of an active, responsible, democratic citizenry. While such skills, values and attitudes are communicated through the hidden curriculum, at a formal curricular level they are explicitly provided for in the Social, Personal and Health Education (SPHE) curriculum. According to the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (1999), SPHE aims to provide “… particular opportunities to foster the personal development, health and well-being of the individual child, to help him/her to create and maintain supportive relationships and become an active and responsible citizen in society” (p.2). Circle time is promoted as a particularly effective method for fostering such social, emotional and moral development (Mosley, 1996). Existing national and international research highlights the popularity of the method of circle time amongst primary school teachers and pupils (NCCA, 2008; Miller & Moran, 2007; Clancy, 2002). These studies indicate that teachers perceive circle time to be a democratic forum which fosters pupils’ self-confidence and self-esteem, promotes personal and social skill development and facilitates pupils’ voice and participation rights (Collins, 2011; DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008; Doveston, 2007; Canney & Byrne, 2006; Lee & Wright, 2001). However, the literature also suggests the need to interrogate and trouble the taken-forgranted assumptions which underpin these perceptions of circle time, its benefits and outcomes (Ecclestone & Hayes, 2009; Hanafin, O’Donoghue, Flynn, & Shevlin, 2009; Lown, 2002; Lang, 1998). While research conducted by the NCCA (2008) on the implementation of the SPHE Curriculum documents the widespread use and popularity of circle time in the Irish schools, there is a dearth of literature on the actual practice of circle time and the implications of this practice for pupils. 1 The 2012-2013 cohort of first year Bachelor of Education (B.Ed) student teachers are among the first to have experienced the new SPHE curriculum and the method of circle time at primary and post-primary level. They therefore have the capacity to provide invaluable insights into circle time as practised and experienced in Irish schools. In this context, the current study sought to explore student teachers’ experiences of and attitudes towards the method of circle time and to investigate the impact of this experience on their possible future use of the method in their own teaching. It also sought to probe the extent to which the criticisms of circle time promulgated in the literature were supported by student teachers’ experiences and assertions. While a range of themes were explored, the study accorded particular attention to the areas of development education (DE) and intercultural education (ICE).2 1 The NCCA’s (2008) study found that 81% of teachers use circle time “sometimes” or “frequently” (p.79). In this regard, attention is given to the inclusion of themes pertaining to equality, human rights and social justice. 2 4 1.2 Circle Time: A Historical Overview The origins of circle time in an education context are obscure, however some commentators point to the work of Ballard (1975) in the USA for its earliest iteration (Lang, 1998). Its roots are in psychology, with Housego and Burns (1994) identifying Karl Rogers as a key figure in the development of “warm and non-judgemental settings in which to reflect and develop self-esteem” (p.26). Circle time was initially introduced to Ireland in the early 1990s by its main proponent in the UK, Ms. Jenny Mosley (whose model is referred to hereafter as the “Mosley Model”). Its advancement was assisted by the introduction of SPHE in the revised Irish Primary Curriculum in 1999, and the promotion of circle time (referred to in curriculum documents as “circle work”) as an effective teaching method. Its implementation was also facilitated by the provision of continuing professional development for teachers in SPHE in the form of evening and summer courses from the mid- to late- 1990s onwards.3 In the Mosley literature, circle time is promoted as a method which enhances selfesteem, promotes positive behaviour and self-discipline, and facilitates the establishment and maintenance of good relationships in schools (Mosley 1993, 1996, 1998, 1999). The Mosley Model involves class meetings and a behaviour management system with ground rules, rewards and sanctions.4 The focus of the current study was the “class meeting” referred to hereafter as “circle time.” Under the Mosley Model, a typical circle time session adheres to the following format: an opening activity or game, a round (using a speaking object), an open forum discussion, an opportunity to celebrate success and a closing activity or game (Mosley, 1996, pp. 99-102). Interestingly, the Mosley Model differs from the model espoused in the SPHE Curriculum, where there is less emphasis on games and more on making the learning concrete through the use of written exercises (NCCA, 1999). 1.3 Overview of Report This chapter has provided a contextual background for the current study. Chapter Two provides a critical review of the literature pertaining to circle time, while Chapter Three delineates the methodological framework and the various stages of the research process. Chapter Four presents a synthesis of the study’s most significant findings. Finally, Chapter Five considers the theoretical and practical implications of the current study for schools and the academy and makes suggestions for future research. 3 Evening and summer courses, for example, were provided by the Walk Tall Support Service at primary level and by groups dealing with substance misuse prevention programmes at post-primary level. Walk Tall is a substance misuse prevention education programme spanning all classes at primary level. 4 More detail of the Mosley Model is outlined in Chapter Two of this report. 5 Chapter Two: Literature Review 2.1 Introduction Despite circle time’s prevalence in schools and an abundance of promotional literature extolling its benefits, there is remarkably little academic research on its theory and practice, particularly in the Irish context. There is a particular dearth of literature which analyses the theory and practice of circle time through a critical lens. In this context, this chapter seeks to engage critically with existing promotional and academic literature and to problematise some of the assumptions which underpin the concept of circle time. In Ireland, two major studies (DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008) have examined the implementation of SPHE in Irish schools. While they offer important insights into the teaching of SPHE, they provide little detail on the method of circle time. However, the NCCA study indicates that 81% of teachers use circle time “sometimes” or “frequently” (p.79); while the DES (2009) study reports that the participating teachers “competently implemented....circle-time activities” (p.90). Collins’ (2011) small-scale doctoral research on circle time, which involved observing the practice of circle time in five primary classrooms, provides the only identified data on the conduct of circle time in the Irish context. 2.2 Circle Time Promotional Literature The dominance of Jenny Mosley in both the British and Irish circle time promotional literature is undisputed. Collins’ (2011) research indicates that Irish teachers are largely following the Mosley Model with some adaptations that are not always helpful as will be outlined later. Mosley describes circle time as “an ideal group listening system for enhancing children’s self-esteem, promoting moral values, building a sense of team and developing social skills” (Mosley, 1996, p.33). However, as will be discussed in the following sections, the validity of some of these claims and similar claims made by other proponents are contestable. 2.2.1 An Over-Reliance on Teacher Perception? It has been argued that there is little evidence, either empirical or theoretical to support some of the claims made by circle time’s key proponents (Lown, 2002; Lang, 1998). Indeed, in the British context, Lang (1998) argues that “benefits are presented either as acts of faith or as common sense” (p.9). A number of studies have investigated the effects of circle time on self-esteem (a key focus in the circle time promotional literature). Kelly’s (1999) research focused on children with low self-concept, while Miller and Moran (2007) measured changes in self-worth and self-competence. While these studies provide evidence of gains in these areas, there is a tendency to rely on teacher or researcher observations for assessment purposes. This is problematic as teachers’ ability to identify children with high or low self-esteem is questionable (Miller et al., 2005). Other research has sought to promote and measure gains in social skills (Moss & Wilson, 1998; Doveston, 2007; Canney & Byrne, 2006). Again, the researchers indicate gains but provide little evidence of how the gains are measured. Research which examines the effects of circle time on the social skills of children with special needs, including those with educational (Galbraith & Alexander, 2005) and social and emotional needs (Lee & Wright, 6 2001), also suggest gains but in some instances the use of other interventions at the same time raises questions as to what made the difference. In the Irish context, research by Clancy (2002) with children with specific learning difficulties, their teachers and parents, found that all groups were consistently positive about circle time. However, it is unclear whether there were any measurable benefits arising from use of the method. The lack of rigour evident in some of the studies mentioned raises questions about the reliability of their findings in relation to the benefits of circle time. 2.2.2 Is Circle Time a Safe Space? Mosley’s circle time is mediated by a series of ground rules, including the necessity for participants to signal when they wish to speak, and to avoid put-downs, interruptions and the specific naming of anyone in the circle in a negative way. Participants also have the right to “pass” if they do not wish to speak during a round and the right speak at the end of a round if they change their minds (Mosley, 1996, p.35). Mosley (1993) suggests that children should be encouraged to say as much as is “safe” in circle time (p.116). On the face of it, these rules appear to safeguard children’s right to a voice as well as their right not to speak, and to promote an esteeming and safe space within which children can develop the personal and social skills and values that are the aims of the method. However, Collins (2011) found that the public nature of circle time has the potential to erode children’s privacy, while inappropriate responses from pupils and an inability to react quickly to events in the circle can undermine the premise of the circle as a safe space. A disquieting aspect of this research was an ambivalence on the part of some teachers in relation to the “pass rule” (Collins, 2011). The imposition of a confidentiality rule in some classrooms in this research, while appearing to safeguard children’s contributions in the circle, also limited their potential for influence (Lundy, 2007). Notwithstanding these challenges however, Collins found that teachers were positive about the method’s power to provide enjoyment, a sense of safety and ease of communication in the classroom context. Another aspect of the Mosley Model that generates some controversy is the focus on individual problem-solving during circle time. As has been argued elsewhere, this has the potential to expose children and their problems in a public forum and therefore has privacy implications (Hanafin et al., 2009). Hanafin et al. identified circle time among a number of classroom practices as “an opportunity for public exposure of both private and family issues” (2009, p.4). If conceptualised as a problem-solving forum, it is possible that circle time can be misappropriated or viewed as a counselling session (Ecclestone & Hayes, 2009). However, Collins (2011) argued that evidence on the ground suggested that teachers did not view their role as counsellors or therapists, and that engagement in circle time was best described as “counselling-lite” (p.168). While there is some evidence to suggest that participation in circle time sessions can be beneficial for pupils, particularly with regards to social skill development, it is important that all claims made by its proponents are substantiated with robust empirical evidence. 2.3 Citizenship, Development and Intercultural Education In the Irish context, the various sub-fields which nest under the umbrella of citizenship education, such as development and intercultural education, democratic education and human rights education, are provided for in the “Myself and the Wider World” strand of 7 the SPHE curriculum. However, research indicates that this strand is frequently neglected by primary teachers in favour of SPHE’s other two strands, “Myself” and “Myself and Others” (Collins, 2011; DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008). Interestingly, despite the fact that human rights education is firmly located in the SPHE curriculum, human rights and responsibilities are not mentioned in either of the reports conducted by the NCCA or the DES. This lack of attention, by two of the most important education structures in the State, is arguably symbolic of the low status attributed to human rights, development and intercultural education in schools. Notwithstanding this, circle time is conceptualised as an important method in this field and is recommended in the NCCA’s Intercultural Education Guidelines (2005). The NCCA promotes it as a safe space where pupils can engage in discussions about intercultural issues. Similarly, Holden (2003) contends that “circle time provides a good starting point for many of the social and moral issues which are linked to citizenship” (p.27). As the circle formation seeks to be non-hierarchical, with the teacher having to adhere to the same ground rules as the students (Canney et al., 2006), it can be conceptualised as an important democratic practice which challenges traditional student teacher power asymmetries (Kavanagh, 2013). Similarly, if students rather than teachers set agendas during circle time sessions, it enables students to exercise more power than more traditional teaching methods and therefore has the capacity to be authentically democratic (Kavanagh, 2013). However, Collins’ (2011) research indicates that circle time sessions at primary level are predominantly teacher-driven. Circle time is also conceptualised as a forum which facilitates students’ participation rights, particularly students’ right to express their views and opinions. However, as has been suggested by Collins (2011) in her analysis of the authenticity of circle time, the extent to which what happens in circle time extends beyond the circle time session is questionable. Adopting the concepts of space, voice, audience and influence from Lundy’s (2007) participation model, Collins argues that while circle time facilitate space (the circle forum itself), voice (turn taking, listening, sharing of opinions) and audience (teacher & students) there is little evidence of suggest that circle time facilitates influence, particularly outside the classroom. 2.4 Conclusion Existing research highlights the popularity of the method of circle time amongst primary school teachers and primary school pupils. Teachers perceive circle time to be a democratic forum which can deliver positive self-esteem, enhanced relationships and skills, and promote collegiality in the classroom and school setting, which reflect the claims made in circle time’s promotional literature. However, we argue that there is a weak evidence base with regards to some of these claims and that circle time appears to be evolving in a way that does not necessarily either facilitate the realisation of its stated aims or provide an authentic space for the emergence of democratic or rights-based education. The following chapter outlines the research that was undertaken with student teachers about their perceptions of circle time. 8 Chapter Three: Research Design and Process 3.1 Introduction This chapter provides a detailed account of the methodological framework employed in the research undertaken. It provides rationales for the selection of the study’s methodology (mixed methods), participants (first year student teachers), sampling procedures (multi-stage), research methods (questionnaire & semi-structured interviews) and research tools (Survey Monkey). It also details the ethical considerations which informed the study, data collection, data analysis and data validation procedures. The following diagram summarises the methodology employed: Figure 1: Methodological Framework Method: Questionnaire Tool: Survey Monkey Participants: First Year B.Ed Students 200 1st Year B.Ed. Students 100: St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra. 100: Mary Immaculate College, Limerick. Mixed Methods Methodology Method: Semi-Structured Interviews Sampling: Multi-Stage Sampling 1. Purposive Sampling 2. Random Sampling 3. Convenience Sampling Research Questions Question 1: Question 2: 3.2 What is your experience of the method of circle time in your education to date? What effect will that experience have on your own use of the method of circle time? Mixed Methods Methodology A mixed methods approach was adopted in order to augment the breadth and depth of the study and to provide a richer and more nuanced understanding of student teachers’ past experiences and possible future use of circle time (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Greene, Caracelli, & Graham, 1989). The two largest primary sector teacher education colleges were selected as the target research sites due to the access they provided to a large number of first 9 year student teachers (800) and due to the researchers’ personal contacts in each college. First Year students were selected as they are among the first cohort of Irish students to have experienced SPHE throughout all of primary and post-primary school and, as SPHE is not offered in first year college courses, attitudes towards circle time could not be influenced by their college experiences of circle time. 3.3 Ethical Considerations: Negotiating Access, Facilitating Voluntary Participation and Informed Consent Ethical approval was sought from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of St. Patrick’s College Drumcondra and Mary Immaculate College Limerick. Once attained, the ethical protocols set down by both Colleges were carefully adhered to during all stages of the research process. The opening page of each survey was comprised of an informed consent form. This form clearly explicated the nature and purpose of the study and provided a brief description of the methodology of circle time. It outlined the voluntary nature of participation and participants’ right to withdraw consent at any time. It delineated the steps taken to protect participants’ privacy and anonymity, and the possible benefits and risks associated with participation. Those interesting in participating were invited to tick two boxes to indicate their willingness to participate and their understanding of all of the content presented in the informed consent form. The provision of this form helped to overcome possible ethical concerns relating to matters of coercion, deception, exposure to mental stress and encroachment on participants’ privacy (Denscombe, 2007; Robson, 2005). Following approval, a small pilot study was undertaken in spring 2012 which allowed instruments and methods to be tested in advance of the main study which was conducted in autumn of the same year. 3.4 Research Methods Given the nature of the research questions and the profile of the target population, a survey constructed using the on-line data collection tool Survey Monkey was deemed the most appropriate method for gathering data. Survey Monkey’s accessibility and efficiency in generating surveys, collecting web-based responses and filtering results made it a pragmatic and effective research tool. The combination of close-ended and open-ended questions facilitated the collection of a wide range of data including information on students’ attributes (gender, age, ethnicity, schooling history etc.) and their understandings, experiences and perceptions of and attitudes towards circle time. Survey Monkey facilitated the storing, management, organisation and analysis of the gathered data. It also enabled the researchers to access the gathered data independently of one another. Prior to the distribution of questionnaires, a short presentation was given to First Year student teachers in both colleges explaining what the research was about and how they might participate. Following this presentation, the URL link generated by Survey Monkey was distributed via email to a random sample of 100 student teachers in each of the two participating colleges. Students’ e-mail addresses were selected at random from lists provided by the registrars in both colleges. 10 A number of steps were taken to encourage a high response rate, including a one euro donation to charity for every survey completed, and an outline of the benefits of participation for student teachers and the wider education community. It was anticipated that questionnaires would be supplemented with focus group interviews in order to gain a deeper insight into student teachers’ experiences of circle time and the impact of these experiences on possible future use of the method (Denscombe, 2007; Robson, 2005).5 Student teachers were invited to participate via the survey (convenience sampling) and to supply an email address if interested. An incentive was offered in the form of a lunch voucher to try to encourage participation. Five respondents indicated interest in participating and following a period of one month were contacted to make mutually suitable arrangements. Two students responded and a time was negotiated. However, on the day of the arranged focus group only one student attended, so a semi-structured interview was conducted instead. This was subsequently transcribed and sent to the participant for member checking. This semi-structured interview allowed us to gain a more in-depth understanding of the participant’s past experiences of circle time and possible future use. It is a source of regret that we could not entice more student teachers to participate in this way in spite of our best efforts. 3.5 Response Rate The Survey Monkey URL was e-mailed to 200 students, 100 students in each of the colleges of education. One-hundred-and-two surveys were returned, a response rate of fiftyone percent. When stratified by gender, males accounted for 13.3% of responses and females 86.7%. Two-thirds (66.3%) of respondents were attending St. Patrick’s College and onethird Mary Immaculate College (33.7%). Of the 102 returned surveys, 65 (63.7%) were fully completed and 37 partially completed. This resulted in data set variance between questions. As a consequence, where relevant, the number of respondents who answered particular questions (denoted using “n”) is provided in the presentation of findings. 3.6 Data Analysis Data analysis was conducted using Survey Monkey. This package was used as it had been used to construct the survey and the “categories” structure was deemed particularly useful for storing, organising, managing and coding the gathered data. Data was read and reread and recurring language and themes identified. As these themes emerged, the data was coded line by line. This approach is very similar to Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) Grounded Theory approach of “open coding” (as cited in Creswell, 2007). They describe this as the process of “breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualising, and categorising data” (as cited in O’Donoghue, 2007, p.61). Open codes were therefore grounded in the raw data. The constant comparative method was used and the content of categories constantly reread and examined and data transferred between categories when necessary. 5 While the researchers initially sought to conduct two focus group sessions, one in each of the participating colleges, a very low response rate meant that this was not possible. 11 3.7 Validation of Data In endeavouring to ensure the study’s validity and reliability, from the outset, every effort was made to ensure that the methods used to collect data and the data itself were appropriate for the purpose of the study; recorded accurately and precisely and analysed carefully (Denscombe, 2007). While acknowledging that objectivity is a chimera, the researchers endeavoured to present balanced findings by being reflective, reflexive, openminded and self-monitoring throughout the research process (Denscombe, 2007). 3.8 Conclusion This chapter has outlined the methodological choices made and their rationales. It has provided a map of the research journey. While acknowledging limitations, particularly in relation to the inability to hold the focus group interviews, the findings nonetheless provide valuable insights into student teachers’ perceptions of circle time in their school careers and how this might affect their own use of the method. These findings are outlined and explored in the next chapter. 12 Chapter Four: Findings 4.1 Introduction This chapter presents and critically analyses student teachers’ experiences of circle time during their primary and post-primary schooling, examining themes, rules, conduct and respondents’ positive and negative experiences of the method based on the data gathered. It also explores student teachers’ possible future use of circle time before concluding with a summary discussion of the chapter. 4.2.1 Provision of Circle Time As is evident from the above graph, respondents indicated that they were most likely to experience circle time during the middle years of primary school, particularly during second (56.1%) and fourth (54.5%) classes and least likely to experience circle time in primary school during junior (34.8%) and senior (37.9%) infants. It is possible that lower reporting in those classes may be linked to pupils’ cognitive maturity and their ability to differentiate between teaching methods during the early years of primary school. Respondents were equally likely to experience circle time in sixth class of primary school and first year of post-primary school (42.4%), with experiences declining thereafter, particularly during examination years (3rd Year: 19.7% & 6th Year: 16.7%). This decline during examination years and a concomitant increase during transition year (up by 18.2% from 3 rd Year) suggests that as a teaching method, circle time is more likely to be used during years when teachers and pupils are under less academic and time pressure. 13 4.2.2 Themes Exploring During Circle Time The majority of respondents indicated that bullying (69.7%) was the most common theme explored, followed by relationships (62.1%), feelings (54.5%) and issues around identity and belonging (47%). Reflecting previous research, citizenship (1.5%), similarities and differences (13.6%) and human rights and responsibilities (18.2%) were least likely to be explored during circle time sessions (Collins, 2011; DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008). It is likely that the prevalence of themes such as bullying, relationships and feelings is reflective of the salience of these issues in everyday school life, and the emphasis that the SPHE Curriculum and widely used curriculum resources place on these key themes (for example, the Stay Safe Programme). According to DES (2009), “Learning in SPHE focuses strongly on developing pupils’... capacity to form friendships and relationships with others” (p.77). The dominance of these themes is also reflective of teachers’ and principals’ views of the centrality of cultivating positive, respectful pupil-teacher relations in an affirming school and classroom climate (DES, 2009). The disparities evident between relationships (62.1%) and sexuality education (24.2%) are also reflective of previous research which indicated that teachers accord more curriculum time and are more comfortable with teaching the relationships rather than sexuality components of SPHE (DES, 2009). The NCCA (2008) noted teachers’ “own inhibitions” as a significant barrier to the provision of sexuality education (p.186). 14 The data suggested that the themes most likely to be explored were those which form part of the SPHE strands of “Myself” and “Myself and Others”; while the themes least likely to be explored fell within the third strand of the SPHE curriculum “Myself and the Wider World.” Less than one-fifth of respondents identified a human rights dimension during circle time and only 1.5% of respondents reported discussing issues pertaining to citizenship. Regarding theme selection, whether at primary or post-primary school, teachers dominated. However, at post-primary level, respondents were given significantly more opportunity to negotiate theme selection with teachers. Thirty-seven percent of respondents indicated that theme selection was negotiated with teachers at post-primary level, in contrast to 4.8% at primary level. It is possible that the disparities between respondents’ involvement at primary and post-primary levels may be related to ideologies of childhood immaturity, with teachers viewing younger children as being too cognitively and emotionally immature to engage in curricular and thematic negotiation. Respondents’ perceptions of teachers’ dominance at primary level reflects Collins’ (2011) contention that the focus of circle time sessions at primary level is predominantly teacher-driven. This dominance and perceived high levels of power and control which teachers exercise in a supposedly pupil-centred democratic forum was an aspect of circle time that respondents did not enjoy. Reflecting this, one respondent stated, “The teacher didn’t want us to discuss other topics than the one she had chosen”; while another stated, “When the teacher was talking, i preferred listening to my classmates.” The notion of circle time as a space which provides pupils with “an equal voice” is problematic. As Fielding (2004) argues, “there are no spaces, physical or metaphorical, where staff and students meet one another as equals, as genuine partners in the shared undertaking of making meaning of their work together” (p.309). While circle time provides pupils with opportunities to exercise more power than perhaps other teaching methods, the teacher remains in control and classroom rules continue to apply. On a similar note, Collins’ (2011) research highlighted a lack of evidence of circle time as a forum which facilitates pupils’ capacity to exercise influence and enact agency. She concluded, “Children’s voice was exercised in a teacher-driven agenda, often linked more to confidence-building than agency” (p.227). In this regard, when analysed through the prism of authentic participation, circle time may be open to charges of tokenism. In addition, a number of respondents articulated the view that more confident students frequently dominated sessions, with less confident students feeling too intimidated to speak in the circle forum. One respondent stated, “Sometimes the quieter students would be overpowered by the more outgoing/opinionated students in the circle.” In this context, it could be argued that counter to its aims, in addition to reproducing the hierarchical relationship which characterises pupil teacher relations, circle time can be a forum which marginalises less confident pupils, rather than giving them “an equal voice.” In fact, the data suggests that circle time can become a time of considerable anxiety for less confident students. For example, one student stated, “It was a bit scary sometimes having to speak out while everyone watched you”, while another asserted that circle time “could be quite nervewrecking as your turn to speak approached!” While the non-hierarchical nature of the circle is intended to symbolise equality, it can also result in participants feeling unduly exposed. One student stated, “Sitting in a circle enabled everyone to look at you when speaking in contrast to people sitting in rows in front or behind you.” In this regard, the extent to which circle time facilitates “equal” student voice is questionable. While the use of a speaking object and the pass rule are two mechanisms employed in order to safeguard equality of 15 voice, the data suggested that the issue remains problematic for some students and other alternatives need to be considered. 4.2.3 Circle Time Rules The data indicated that rules were broadly similar at primary and post-primary schools. When taken collectively, the rule most commonly mentioned by respondents pertained to turn-taking and its etiquette (n=37). Respondents noted rules including “take turns speaking,” “raise your hand if you wish to speak,” “only one speaker at a time,” “no talking when others are talking” amongst others. Turn-taking was followed by circle confidentiality, “Whatever is said in the circle stays in the circle” (n=32); use of the speaking object, “Only person with speaking stick may talk” (n=24); listening to others (n=23) and respect for others (n=21). When stratified by school level, there was some divergence. At primary level, turn taking (n=24) was mentioned by most respondents, followed by use of the speaking object (n=21) and the confidentiality rule (n=15). At second level, the confidentiality rule (n=17) was mentioned by most students, followed by respect for other students (n=15) and turn taking (n=13). The speaking object appeared to be more of a feature at primary level (n=21) than post-primary level (n=3). It is likely that its decline at second level is related to students’ perceived advanced maturity and self-regulation skills. While rules are arguably necessary to facilitate student voice (turn-taking, listening etc.), they may also hinder the exercise of voice for agency (Collins, 2011). 4.2.4 Conduct of Circle Time While experiences of circle time at both levels are broadly similar, disparities are evident with regard to use of a speaking object and the playing of ice breaker games. Twelve percent of respondents (n=8) mentioned playing ice breakers at primary level, while no respondents mentioned these warm-up activities at post-primary level. This contrasts with Collins’ (2011) research which indicates that warm-up activities or ice-breakers were common features of observed practice. There was no mention of a speaking object at postprimary level. Outlining experiences of circle time at primary level, one respondent states, Everyone sat in a circle (obviously). The teacher sat in the circle also, she/he introduced the topic that we'd be sharing our views/feelings on and gave her views on the subject. She then passed an object of some sort e.g. a marker or pen to the person alongside her indicating that it was their turn to talk. You could only talk if you had the object in your hand. If you weren't comfortable talking on the subject you were allowed to pass the pen on without talking. It appears from the data that the Mosley Model is largely followed at primary level, while there is more variation at post-primary level, reflecting the maturity of the students and possibly less familiarity with the Mosley literature at that level. 16 4.2.5 Positive Aspects of Circle Time The responses in relation to enjoyment of circle time were broadly similar at primary and post-primary level. Respondents indicated that circle time’s capacity to facilitate student voice was the aspect they enjoyed most about it. Students’ responses suggested that as a forum, circle time provided opportunities to “voice my opinions/thoughts,” “express myself,” and “to clearly hear everyone’s opinions.” Students spoke of “enjoying hearing other people’s thoughts.” This reflects the DES’ (2009) research which indicated that 76.5% of pupils enjoyed sharing their views, while 46.6% stated that others like to listen to their views (p. 77). At post-primary level, other positive aspects included the sharing of ideas and stories. A break from work and the “normal routine” was cited as the third most enjoyable aspect at primary (n=17) and post-primary level (n=7). Respondents spoke in terms of circle time providing “a break from the textbooks” and “a chance to get away from our desks for a while.” They enjoyed the fact that circle time “provided a great release from the rigid structure of the classroom” and that “it was different from the usual routine.” Interestingly, while at primary level, issues pertaining to fun and enjoyment were cited by 28% (n=19) of respondents who answered this question (second behind student voice), only 6% (n=4) of respondents mentioned these issues at second-level. While it is difficult to account for this significant disparity, it is possible that students’ increased self-consciousness and discomfort with certain “awkward” topics may account for some of it. Referring to these issues at postprimary level, one student stated, “I didn’t feel comfortable sharing my thoughts most of the time.” In the same vein, another student stated, “As teenagers, I think we were all a little bit more embarrassed to give our opinions on controversial issues, which resulted in some of the sessions being quite awkward.” Similarly, another student asserted, “When some of the more forward girls in my class would start bringing up really personal issues I used to feel uncomfortable...” The difficulties raised by these students are reflective of teachers’ views as expressed in the NCCA (2008) report, where it was noted that addressing “touchy subjects” and eliciting answers from “reluctant” speakers posed significant challenges for teachers (NCCA, 2008, p.131). Other positive aspects for respondents were highlighted when they were asked for memorable moments from their experiences of circle time. Some of these moments focused on developing the skills to deal with real life issues pertaining to peers in the classroom and incidents in the school. One student reported, In 5th class we had a conversation about a team we had played in a school match the previous day. i remember we felt that they were very rough and bullied us and this is one circle time which sticks out in my mind because my class was so angry with the other team and believed there was an injustice. Another remembered, i distinctly remember after sharing a story about being teased over a birthmark how one girl with whom i did not necessarily get along approached me after class and told me very sincerely that she loved my birthmark because it was who i was that i had one. This approval from a peer gave me a lot of self-confidence at the time when it was badly needed and would not have occurred [sic] if it wasn’t for circle time. i also remember how when i raised the story the teacher merely shrugged it off. 17 4.2.6 Negative Aspects of Circle Time The most commonly cited negative aspects of circle time were broadly similar at primary and post-primary level. One quarter of respondents who answered this question indicated that participating in circle exacerbated feelings of self-consciousness (n=18). This was followed by feeling undue pressure to speak (n=16). Illustrative of this, one student stated “sometimes you were put on the spot and some students felt too shy to say what they really felt in front of their peers.” Another stated, “The whole class was paying explicit attention to you.” With regards to feeling under pressure to speak, one student described feeling “Pressure to say something at times when your name was called.” Similarly, another reported disliking that fact that, “We had to have an opinion on everything because we couldn’t move along unless we said something.” Respondents also indicated that they “felt under pressure to volunteer personal information.” Supporting this, another asserted: “… didn’t like it, too personal, was forced to talk”, while another stated, “It sometimes got very personal.” However, it is important to note that practice in this regard is not supported in Mosley’s Model of circle time. Issues mentioned by respondents regarding feeling under pressure to share personal stories support Hanafin et al.’s (2009) contention that practices such as circle time can lead to excessive intrusion into pupils’ private and family lives, thereby undermining pupils’ privacy rights. In this context, it could be argued that while circle time promotes pupils’ participation rights, it is sometimes at the expense of their privacy rights. The negative incidents which were recounted tended to pivot around other students’ emotional distress because of personal or family difficulties. One student reported, One of the girls got very emotional because she had been bullied in first year and it was her first time talking openly about it. She was crying hysterically and it really shocked me... Another stated, “… a girl broke down crying while discussing a topic very personal to her.” In a similar vein, another stated, “I remeber [sic] a girl breaking down one time sobbing that she was teased and told she must have cancer because of her alopecia.” The literature indicates that circle time’s capacity to facilitate the enhancement of pupils’ self-esteem and self-confidence is one of its most important benefits (DES, 2009; NCCA 2008; Mosley, 1993, 1996). Interestingly, no respondents mentioned self-esteem when completing the questionnaires and confidence was only mentioned twice, once in a positive context (see previous section) and once in a negative context. In the negative context, the student stated, I don't really like to talk in front of large groups of people, therefore i didn't enjoy circle time. I probably would have enjoyed it more if the discussion had begun in smaller groups and then moved onto larger groups, therefore my confidence in speaking in front of large groups of people would have eventually grown. The negativity found in the current research points to an inconsistency between claims in the promotional and research literature on circle time and students’ own perceptions. Reflecting this, Collins’ (2011) argued, “If one were building the rationale for circle time on self-esteem, one would be on shaky foundations” (p.222). 18 Respondents also reported more overtly negative experiences than positive, specifically around the issue of confidentiality and exposure to ridicule. One student stated, “Although one of the ground rules was that we were not to mock people about what they said, it still happened after the class in question.” Respondents also reported instances of pressure to expose others, I remember that one teacher we had made us stand up and say the name of someone we felt was bullying us if we wanted to, it wasn't a good experience i think it would have been better if the teacher talked to them alone not in front of the class. Notwithstanding these shortcomings, congruent with existing literature, there was evidence in this study to suggest that circle time improved interpersonal relationships and classroom culture and promotes personal and social skill development (Canney et al., 2006; Doveston, 2007; Lee et al., 2001; Tew, 1998). Examples of respondents’ comments included, “Got to know classmates better”; “Circle time also helped to form closer bonds or a more community spirit in the classroom”; “Bonding with others in my class”, and “I enjoyed the connection it helped me to gain with my classmates and teacher.” 4.2.7 Effective Circle Time Sessions: Teacher Skills The following diagram illustrates the kinds of skills respondents saw as important for teachers in circle time: In tandem with this, respondents were asked to outline the skills they felt that teachers were lacking when conducting circle time sessions. Teachers’ inability to make the circle a safe space emerged as the most salient factor (n=12) followed by their perceived 19 unwillingness to share their own personal experiences with the students in their classes (n=10). One respondent’s comment succinctly captures both of these perceived deficits: “teachers didn’t share their own experiences with us and allowed other people to laugh when a person was talking.” Respondents cited the lack of a good rapport between teachers and students as a serious obstacle to effective circle time sessions. The reasons given for this varied from teachers’ personal characteristics, (“quite strict and unapproachable”) to not knowing the teacher well enough. One student asserted, A lot of the time, circle time was where bullying was discussed. This was often with a teacher we didn't know well, therefore there was not a relationship between the teacher and pupils. This resulted in an ineffective circle time. Similarly, another respondent stated, The teachers lacked understanding and empathy, they didn't share their own stories and the relationship between the teacher and the students was poor. It is likely that these issues were manifest at post-primary rather than primary level as at primary level students only have one class teacher and therefore have the opportunity to know that teacher quite well. A lack of control over students, empathy and organisational and planning skills also emerged as important factors. One student stated, “They lacked organisational skills and the ability to control the class.” Capturing a number of salient issues, one student stated that teachers, …often lost control of the group, allowed students to say offensive things and didn’t correct them - homophobia, transphobia, racism – allowing these things to go without any response made those of different races and LBGT students fearful and ashamed. Reflecting this, when asked if there was anything that could have made their experience of circle time better, similar issues emerged. These included the need for teachers to make the circle a safe space (n=6), control and planning and organisation (n=3). One respondent asserted “If a safe environment was created it would have made the students more confident to speak out.” Another stated, “The teacher could have gotten the class to write down their thoughts, and then read them out anonymously to stop them feeling embarrassed.” Related to the notion of the circle as a safe space, respondents also reported the need for teachers to maintain control in terms of student misbehaviour but also to control the more vocal students who often dominated sessions. One student asserted, “My teacher could have stopped the more vocal girls from always being the ones to give their opinion.” Issues also emerged with regards to student participation. Some respondents felt that students should be given more sharing opportunities (n=4) and that teachers should ensure equality of opportunity with regards to participation (n=3). One student asserted, Some teachers stuck rigidly to filling out the worksheets and reading case studies, which were the same every year, so we didn’t get the opportunity to share our own feelings and experiences, they could have made the session more about us personally. 20 Reflecting the need for equality of participatory opportunity, another student stated, “All students shound [sic] have been givin [sic] equal opportunity to share.” 4.2.8 Use of circle time in own teaching The following graph provides respondents’ perceptions on the possible use of the method of circle time in their own teaching. When asked what would assist them in using the method of circle time, respondents’ answers fell into three broad categories: the development of skills in how to build strong relationships with pupils characterised by trust, care and understanding; the need for circle time to be regulated and controlled by setting and adhering to rules; and the need for resources which accommodate and support circle time. These findings correlate strongly with previous research regarding the need for positive relationships between pupils and teachers (DES, 2009, Collins, 2011). The curricular areas most suited to the use of circle time were identified as SPHE (82.5%), Drama (82.5%) and Religion (70%). The most suitable themes, according to the research participants, were bullying, relationships, friendship, feelings, safety and discrimination. One respondent’s comments succinctly capture many of these interrelated themes, “Issues that affect young people - bullying, racism, discrimination, friendships, family, school work, safety, happiness, sadness.” More generally, respondents indicated that circle time should be a forum where issues “that affect everyone in everyday life” are discussed and where issues which emerged during the course of curricular work can be further probed and dissected. While some respondents indicated that circle time was an 21 appropriate arena for the discussion of “controversial” and “embarrassing or awkward topics”, others suggested that topics should remain “light-hearted” and that themes which “...hit a nerve with the students and cause them to clam up and stop sharing their opinions with the class” should be avoided. Such a conceptualisation is problematic given the SPHE’s pivotal role in dealing with perceived controversial or sensitive material, but is consistent with DES (2009) and NCCA (2008) findings in relation to teachers’ attitudes around sensitive areas of the curriculum. 4.3 Conclusion The data gathered in this research suggests as a teaching method, circle time is more likely to be used during years when teachers and pupils are under less academic and time pressure. Reflecting previous research (Collins, 2012; DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008), respondents were more likely to explore themes consistent with the strands “Myself” and “Myself and Others” than “Myself and the Wider World.” Findings indicate that circle time provided respondents with the opportunity to share their personal stories, views and opinions and to participate in discussions with their peers. However, the authenticity of circle time as a democratic forum which facilitates authentic participation and fosters self-esteem and self-confidence is questionable. The data indicates that teachers dominate theme selection, particularly at primary level. Encouragingly, however, students are provided with opportunities to negotiate theme selection at postprimary level, which may be viewed as more democratic and authentic. Circle time’s capacity to facilitate “equal voice” between teachers and pupils and the pupils themselves is also questionable. As has been articulated by a number of respondents, more confident pupils frequently dominate sessions and less confident students feel intimidated to speak in the large circle forum. The data also suggests that circle time can become a time of considerable anxiety for less confident students and can infringe students’ privacy rights resulting in emotional distress for some pupils. The circle time literature indicates that the promotion of self-esteem is a key aim and benefit of circle time (Mosley, 1993, 1996) and research conducted with teachers supports the view that engaging in circle time enhances pupils self-confidence and self-esteem (DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008). This was not supported by the current study. The circle time literature also indicates that circle time plays a key role in skill development (Canney & Byrne, 2006; Doveston, 2007; Lee & Wright, 2001; Tew, 1998). The research outlined here supported this with respondents indicating that circle time provided them with opportunities to develop listening skills, turn taking skills, communication skills etc. Respondents indicated that to be effective circle time sessions need to be conducted by caring and kind teachers, who have a strong rapport with pupils, are willing to share personal experiences and are able to formulate structured, well-organised learning experiences in a safe space where all pupils have the opportunity to exercise voice but also the choice as to whether they wish to or not. Despite a number of negative experiences associated with engaging in circle time sessions, 72.5% of respondents indicated that they intended to conduct circle time session in future with a further 20% indicating that they may use it following further experience. Respondents identified many benefits associated with circle time as succinctly articulated by one student, “Got to know classmates better, felt like i had a voice, break from routine, felt valued.” Respondents also recognised circle time’s 22 capacity to deal with “real life issues” and “topic relevant to us”. Like other teaching approaches, circle time has its shortcomings and indeed a number of tensions exist between teacher regulation and pupil voice and between pupil protection and the discussion of controversial issues, amongst others. Based on this and other research, it appears that circle time has transformative potential as a democratic forum which facilitates student voice and empowerment. However, in order to realise this potential, critical engagement and dialogue within the field is necessary to clarify aims, priorities and practices. Bearing this in mind, the final chapter of this report makes recommendations based on the current and other research. 23 Chapter Five: Summary and Recommendations 5.1 Introduction This chapter provides an overview of the research report, addresses the implications of its findings and makes recommendations for future teacher education and research. 5.2 Summary of the Report The popularity of circle time in Irish primary schools has been established (NCCA, 2008). Its origins are rooted in psychology, with one of its key aims being the promotion of positive self-esteem. It was introduced into Ireland in the early 1990s by its main proponent in the UK, Ms. Jenny Mosley, and while the practice has evolved in Ireland, this has not always been in a productive and beneficial way (Collins, 2011). A review of the literature indicated that research into the practice of circle time in the Irish context is extremely limited. Moreover, this research focuses predominantly on practice at primary level. The research that exists is almost exclusively positive in its claims that circle time enhances self-esteem, improves social skills and positive relationships. However, a lack of rigorous testing, and an overreliance on teacher perceptions in some studies, casts doubt on the validity of some of these claims. In an effort to address some of these research deficits, funding was sought and granted by the DICE Project to undertake research with First Year Bachelor of Education student teachers. Using a mixed methods methodology (questionnaire & interview), the current research sought to explore student teachers’ experiences of and attitudes towards the method of circle time, and to investigate the impact of this experience on their possible future use of the method in their own teaching. Respondents were drawn from St. Patrick’s College and Mary Immaculate Colleges of Education, and due regard was taken in relation to ethical and other research considerations before, during and after the research. While a range of themes were explored, the current research accorded particular attention to the areas of development education (DE) and intercultural education (ICE). The current research provided evidence that pupils were more likely to experience circle time in the middle years of primary school and First Year and Transition Year at postprimary level. Bullying was the most common theme explored, followed by relationships, feelings and identity/belonging issues. Less than one-fifth of respondents identified a human rights dimension during circle time and only 1.5% of respondents reported discussing issues pertaining to citizenship. However, findings also suggest that respondents believed that issues such as racism and discrimination should be discussed during circle time sessions. Based on the current research, teachers are most likely to set the agenda for circle time, particularly at primary school level, which challenges the notion of circle time as a democratic space. There are many aspects of circle time which respondents greatly enjoyed, in particular the opportunity to share their personal stories, views and opinions and to participate in discussions with their peers. Improved interpersonal relationships were also highlighted as a feature of circle time. However, the current research also indicated that there were aspects that students did not enjoy, including teacher dominance during theme selection, the vocal dominance of confident students, exacerbated feelings of self-consciousness, and undue 24 pressure to volunteer information during circle time sessions. Some students’ emotional distress was also a source of negativity. For some students, the circle was not the safe space that its advocates might envisage. The need for teachers to have a good relationship with students as a prerequisite for successful circle times was highlighted, as well as the ability to show empathy and understanding. Notwithstanding the negativity expressed by respondents however, just under three-quarters of them indicated that they intended to conduct circle time sessions in future with a further one-fifth indicating that they may use it following further experience. Development of skills in the area of relationship-building was identified as an aide to circle time implementation, as was the ability to satisfactorily regulate the circle. In addition, resources which would support teachers in conducting circle time were also highlighted as desirable. Supporting the critique provided in Chapter Two, this research indicated that respondents did not appear to see a relationship between circle time and enhanced selfesteem or self-confidence. Moreover, for some students, circle time was often a period of considerable anxiety dominating by confident vocal pupils, rather than an esteeming and democratic space. A strength of the current research is the foregrounding of the student voice in the presentation of findings. The implications of listening to that voice for the future development of circle time is what is now given attention. 5.3 Recommendations The willingness of student teachers in the current research to use circle time in their own teaching says much about its appeal in the classroom context. This positivity, if harnessed, could potentially allow for circle time to become a more authentic democratic forum not only for personal and social development, but also for discussion and exploration of “wider world” issues pertaining to citizenship, DE and ICE. The recommendations outlined here are offered with this broader vision in mind. From the current research and other Irish research (Collins, 2011) it appears that there is a need to re-visit the basic principles of circle time, particularly in relation to providing participants with choice regarding their contributions, and ensuring the safety of all. This points to provision of on-going training for practising teachers and a review of existing preservice training in this regard. It may be that a shift in emphasis is required which foregrounds relationship, empathy and trust-building - skills that student teachers have highlighted as essential for teachers in circle time. The findings also indicate that students wish to discuss real life issues during circle time sessions, particularly issues relating to discrimination, equality and racism. In this context, circle time provides an ideal forum for discussing issues pertaining to citizenship, human rights and intercultural education. It appears that teachers would benefit from the opportunity to explore these issues to inform and underpin their conduct of circle time. Teachers may also need additional resources to assist them in conducting these more outerfocussed circle times, as much of the promotional literature has a personal and/or social skills focus (Mosley, 1996; 1998). If these resources were focused on the wider world strand of the SPHE Curriculum it would address the low implementation of this strand at primary level (DES, 2009; NCCA, 2008). It is possible that a similar situation exists at post-primary level, 25 however more research is needed at that level into circle time to establish what is happening there. If circle time is to realise its potential as an authentic democratic forum, pupils must at the very least be given the opportunity to negotiate circle time themes with their teacher. A suggestion box in classrooms would provide a simple solution to this identified problem. This could be augmented by open-ended discussions in circle time, where pupils are encouraged to set and take responsibility for agendas. While there is some evidence that this is already happening at post-primary level, if it were to become the norm it would allow circle time to become truly democratic. However, there needs also to be acknowledgement that, at both levels, the teacher, by virtue of his/her position, retains a stronger voice than the pupils. In this context, circle time would be more usefully conceptualised as a forum which provides pupils with a greater opportunity to share their thoughts and views in a safe pedagogical space. Finally, the literature review conducted for this report indicated an overly-optimistic, positive view of the effects of circle time on pupils in schools. This contrasts with the negativity reported in the current research. There is a definite need to conduct more research which foregrounds the voice of participants in circle time. Addressing the dearth of research at post-primary level in Ireland needs to be prioritised and must include data-gathering on what is actually happening on the ground at that level, as well as students’ views on its impact. We hope to continue research in this area, and to contribute to the positive evolution of circle time into the future. 26 References Canney, C., & Byrne, A. (2006). Evaluating circle time as a support to social skills development – reflections on a journey in school-based research. British Journal of Special Education, 33(1), 19-24. Clancy, F. (2002). Circle time: An examination of the process and how it is perceived by a group of pupils experiencing specific learning difficulties, their parents and teachers. (Unpublished M. Ed. Psych. Thesis), University College Dublin, Dublin. Collins, B. (2011). Empowering children through circle time: An illumination of practice. National University of Ireland Maynooth. Available at http://eprints.nuim.ie/3728/. Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications. Department of Education and Science (DES). (2009). Social, personal and health education in the primary school (SPHE): Inspectorate evaluation studies. Retrieved January 8, 2013, from http://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/EvaluationReports-Guidelines/insp_sphe_in_the_primary_school_09_pdf.pdf Doveston, M. (2007). Developing capacity for social and emotional growth: An action research project. Pastoral Care in Education, 25(2), 46-54. Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2009). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. London: Routledge. Galbraith, A., & Alexander, J. (2005). Literacy, self-esteem and locus of control. Support for Learning, 20(1), 28-34. Greene, J.C., Caracelli, V.J. & Graham, W.F. (1989). Toward a Conceptual Framework for MixedMethod Evaluation Designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11 (3), 255-274. Hanafin, J., O'Donoghue, T., Flynn, M., & Shevlin, M. (2009). The primary school's invasion of the privacy of the child: Unmasking the potential of some current practices. Irish Educational Studies, 35, 1-10. Holden, C. (1998). Citizenship in the primary school: going beyond circle time. Pastoral Care in Education, 21 (3), 24-29. Housego, E., & Burns, C. (1994). Are you sitting too comfortably? A critical look at 'circle time' in primary classrooms. English in Education, 28(2), 23-29. Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33 (7), 14-26. Kavanagh, A.M. (2013). Emerging models of intercultural education in Irish primary schools: A critical case study analysis. St. Patrick’s College Drumcondra: Unpublished PhD Thesis. 27 Kelly, B. (1999). Circle time. Educational Psychology in Practice, 15(1), 40-44. Lang, P. (1998). Getting Round to Clarity: What Do We Mean by Circle Time? Pastoral Care in Education, 16 (3), 3-10. Lee, F., & Wright, J. (2001). Developing an emotional awareness programme for pupils with moderate learning difficulties at Durants school. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 6(3), 186-199. Lown, J. (2002). Circle time: The perceptions of teachers and pupils. Educational Psychology in Practice, 18(2), 93-102. Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journa , 33(6), 927942. Miller, D., & Moran, T. (2007). Theory and practice in self-esteem enhancement: Circle-time and efficacy-based approaches - a controlled evaluation. Teachers & Teaching, 13(6), 601-615. Mosley, J. (1993). Turn your school round: A circle-time approach to the development of self-esteem and positive behaviour in the primary staffroom, classroom and playground. Wisbech: Lda. Mosley, J (1996). Quality circle time in the primary classroom: Your essential guide to enhancing self-esteem, self-discipline and positive relationships. Wisbech, Cambridgshire: Lda. Mosley, J (1998). More quality circle time. Wisbech, Cambridgshire: Lda. Mosley, J. (2006). Step by step guide to circle time for SEAL. Trowbridge: Positive Press. Moss, H., & Wilson, V. (1998). Circle time: Improving social interaction in a year 6 classroom. Pastoral Care in Education, 16(3), 11-17. National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, & Ireland Department of Education and Science. (1999). Primary school curriculum: introduction. Dublin: Stationery Office. National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). (2005). Intercultural education in the primary school, guidelines for schools. Retrieved February 26, 2013, from http://www.ncca.ie/uploadedfiles/Publications/Intercultural.pdf National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA). (2008). Primary curriculum review: Phase two. Dublin: NCCA. O’Donoghue, T. (2007). Planning your qualitative research project. interpretivist research in education. Abingdon: Routledge. An introduction to Tew, M. (1998). Circle time: A much-neglected resource in secondary schools? Pastoral Care in Education, 16(3), 18-27. 28