Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

www.elsevier.com/locate/paid

GoldbergÕs ÔIPIPÕ Big-Five factor markers: Internal

consistency and concurrent validation in Scotland

Alan J. Gow *, Martha C. Whiteman, Alison Pattie, Ian J. Deary

Department of Psychology, School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences,

University of Edinburgh, 7 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9JZ, Scotland, UK

Received 12 May 2004; received in revised form 16 July 2004; accepted 17 January 2005

Available online 2 March 2005

Abstract

GoldbergÕs (2001) IPIP Big-Five personality factor markers currently lack validating evidence. The

structure of the 50-item IPIP was examined in three different adult samples (total N = 906), in each case

justifying a 5-factor solution, with only minor discrepancies. Age differences were comparable to previous

findings using other inventories. One sample (N = 207) also completed two further personality measures

(the NEO-FFI and the EPQ-R Short Form). Conscientiousness, Extraversion and Emotional Stability/

Neuroticism scales of the IPIP were highly correlated with those of the NEO-FFI (r = 0.69 to 0.83,

p < 0.01). Agreeableness and Intellect/Openness scales correlated less strongly (r = 0.49 and 0.59 respectively, p < 0.01). Correlations between IPIP and EPQ-R Extraversion and Emotional Stability/Neuroticism

were high, at 0.85 and 0.84 respectively. The IPIP scales have good internal consistency and relate

strongly to major dimensions of personality assessed by two leading questionnaires.

Ó 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Personality; IPIP Big-Five factor markers; Validation

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 131 651 1685.

E-mail address: alan.gow@ed.ac.uk (A.J. Gow).

0191-8869/$ - see front matter Ó 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.011

318

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

1. Introduction

Personality assessment is important in a variety of situations, from academic research to clinical

settings. Individual differences in human personality are often described as being quite comprehensively described by 5 higher-order factors (Matthews, Deary, & Whiteman, 2003), although

an increasing body of evidence suggests that additional factors are required to account for important individual variation beyond that assessed within more traditional 5-factor frameworks (Paunonen & Jackson, 2000); a recent review of 8 psycholexical studies found support for a 6-factor

model across seven languages (Ashton et al., 2004). For the purposes of the current study, however, a 5-factor model is employed due to the general consensus that exists about what those factors are; models with a higher number of factors are not entirely in agreement about what a 6th,

7th or nth factor would be.

2. Recent debate and GoldbergÕs proposal

Goldberg (1999) has argued that scientific progress within the development of personality

inventories has been ‘‘dismally slow’’ (p. 7). He attributes this to the fact that most of the

broad-bandwidth personality inventories developed are proprietary instruments (such as the

NEO PI-R/FFI: Costa & McCrae, 1992), possibly leading to a lack of improvement as researchers require permission from the copyright holders and are charged for each questionnaire used.

However, Costa and McCrae (1999) maintain that proprietary instruments are regularly revised

(several changes were recently suggested to the short form of the NEO in response to a number

of criticisms of the scale (McCrae & Costa, 2004)). However, what may be hampering progress

further is a dearth of comparative validity studies, where two or more inventories are evaluated

on their ability to predict a criterion variable (Goldberg, 1999). Goldberg therefore proposed an

international collaboration to develop an easily available, broad-bandwidth personality

inventory. All researchers could freely use the items in the pool, and disseminate their

findings to improve these. Items were developed and subsequently presented on an internet website; the items are known collectively as the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP: Goldberg, 2001).

The IPIP contains alternate versions of widely used inventories. For example, an IPIP version

of the NEO PI-R (Costa & McCrae, 1992) is available. The IPIP-NEO is available as a 50, 100, or

full 240-item questionnaire. The associations between the proprietary and IPIP versions have been

recorded and are generally encouraging: in the short form of the IPIP-NEO, correlations range

from 0.70 to 0.82 (0.85 to 0.92 when corrected for unreliability) with the corresponding NEO

PI-R factors (Goldberg, 2001). However, it has been suggested that even such high correlations

do not imply that the different versions are truly equivalent (Costa & McCrae, 1999).

3. The IPIP Big-Five factor markers

The IPIP contains not only versions of proprietary scales, but also a number of items known

collectively as the Big-Five factor markers (Goldberg, 2001). The starting point for the creation

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

319

of these items was GoldbergÕs (1992) 100 unipolar Big-Five factor markers (derived from early

lexical studies in English). These trait-descriptive adjectives had been used in a number of studies

(Goldberg, 1992) and suggested 5 broad factors (very similar to those recovered from questionnaire studies), namely Extraversion (or Surgency), Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional

Stability (often regarded as the opposite pole of Neuroticism) and Intellect (or Imagination). The

adjective markers were related to the NEO-PI (an earlier version of the NEO PI-R), and correlations between corresponding scales ranged from around 0.46 to 0.69 (Goldberg, 1992). However, Goldberg (1999) proposed that these adjectives might be improved upon to create

questionnaire items that would provide more contextual information than single words, but still

be more succinct than items in many other inventories. A battery of IPIP items was therefore

administered to a large adult sample, and those which had the highest correlations to the orthogonal factor scores defined by the 100 adjective markers were chosen, with further internal consistency refinement (Saucier & Goldberg, 2002). The IPIP Big-Five factor markers are the result,

with each factor measured by 10 or 20 items and mean internal consistencies of 0.84 and 0.90 for

the 50 and 100-item versions respectively. The items have been correlated with the adjective

markers, and average 0.67 and 0.70 for the short and long versions respectively (Goldberg,

2001). Whilst there is some published work on the adjective markers, and the IPIP versions

of proprietary instruments, there seems to be little published research relating to the Big-Five

factor markers, other than the information provided in Saucier and Goldberg (2002), and on

the IPIP website.

4. The current study

GoldbergÕs IPIP Big-Five factor markers are examined in two stages. The 1st investigates the

factorial structure of the IPIP items and the internal consistency of the IPIP scales in three samples of different ages. In addition, age differences in IPIP scales are examined. The 2nd stage

correlates IPIP scales with the NEO-FFI and the EPQ-R Short Form scales in a sample of

middle-aged individuals, in order to assess the IPIPÕs concurrent validity.

5. Method

5.1. Questionnaires

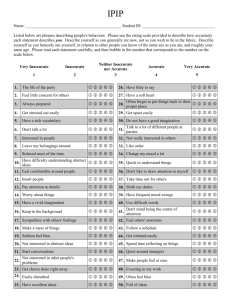

5.1.1. IPIP Big-Five factor markers (Goldberg, 2001)

The IPIP Big-Five factor markers consist of a 50 or 100-item inventory that can be freely downloaded from the internet for use in research (Goldberg, 2001). The current study makes use of the

50-item version consisting of 10 items for each of the Big-Five personality factors: Extraversion

(E), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), Emotional Stability (ES) and Intellect (I). For each

of the items, which are in sentence fragment form (e.g., ‘‘Am the life of the party’’), ‘‘I’’ was added

at the beginning so that the items would be easier to read, and more closely match the other inventories used. Participants were requested to read each of the 50 items and then rate how well they

believed it described them on a 5-point scale (very inaccurate to very accurate).

320

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

5.1.2. NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI: Costa & McCrae, 1992)

This 60-item inventory consists of 12 items each for the 5 factors: Neuroticism (N), Extraversion (E), Openness (O), Agreeableness (A) and Conscientiousness (C). Participants were asked to

mark each item on a 5-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) according to how well it

described them.

5.1.3. Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised Short Form (EPQ-R Short Form: Eysenck,

Eysenck, & Barrett, 1985)

The EPQ-R contains 48 items, 12 each for the personality factors Extraversion (E), Psychoticism (P) and Neuroticism (N), plus a Lie Scale (L). Participants were required to read each item,

and circle either yes or no to show which best described them.

5.2. Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited in three groups.

Student sample (N = 201). A student sample consisting of 201 participants (90 [44.8%] men and

111 [55.2%] women) was recruited, mostly undergraduates at the University of Edinburgh. The

mean age of the sample was 25 years 6 months (sd = 10 years 2 months), ranging from 17 years

9 months to 61 years 11 months. The participants were approached in lectures and asked to complete the IPIP.

General population volunteers (N = 207). Members of the University of Edinburgh Psychology

Volunteer Panel were recruited into the study. These are individuals who responded to advertisements to be potential participants in psychology studies. The IPIP, NEO-FFI and EPQ-R Short

Form questionnaires were mailed to the participants. If there was no response after 5 weeks, a

reminder and a further copy of the questionnaires was mailed. Each returned questionnaire

was checked for omissions or multiple answers. Where corrections were required, these were detailed in a letter sent to participants. Of 273 members of the Volunteer Panel sent the questionnaires, 225 (82%) responded, although of these, 4 refused to complete the questionnaires, 9

were no longer at the listed address and 5 had died. Corrections were requested from 54 participants, and reminders were sent to 83. This led to a final return of 207 questionnaires (76% of

the initial mailing), 61 (29.5%) men and 146 (70.5%) women. The mean age was 55 years 2 months

(sd = 15 years 4 month), ranging from 18 years 7 months to 83 years 2 months (9 participants did

not record their age). Two questionnaires remained incomplete after corrections were requested: 2

items were missing from one IPIP return, and 1 NEO-FFI item was missed by another participant. As detailed in the manual (Costa & McCrae, 1992), the neutral response was imputed for

the missing NEO-FFI item.

Lothian Birth Cohort 1921 (N = 498). Members of the Lothian Birth Cohort 1921 (LBC1921)

were assessed. Their recruitment is described extensively elsewhere (Deary, Whiteman, Starr,

Whalley, & Fox, 2004). The LBC1921 are surviving participants of the Scottish Mental Survey

of 1932 and were mailed as part of an ongoing follow-up. All were aged around 81 at the time

of mailing. The procedure was the same as that described for the general population volunteers

in the previous paragraph. The IPIP questionnaire was sent to 534 members of the LBC1921

(from a list of 569, 32 had died and 3 were no longer contactable at the start of the current study;

this number is greater than previous LBC1921 reports (e.g., Deary et al., 2004), as it includes indi-

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

321

viduals who were subsequently ineligible or did not participate in the main study). Corrections

were requested from 135 participants, and reminders were sent out to 78. This procedure resulted

in 498 returned questionnaires, a response rate of 93%. Of this number, 460 questionnaires were

fully completed (86% of the original mailing), with 38 still partially completed even after corrections were requested or reminders sent.

6. Results

6.1. Structure of the IPIP items

6.1.1. Student sample

From the PCA, the overall measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) was 0.74, whilst the item values were within acceptable limits (the lowest being. 59). This suggests the PCA could be conducted

without having to remove any unsuitable items. The scree plot produced suggested the extraction

of 6 factors accounting for 46.7% of the variance. This is not reported here (details are available

from the authors on request), as the 6-factor solution results mainly from a split of the Intellect

factor into two. In order to examine whether the item loadings were in accordance with the test

construction and theory, 5 factors accounting for 42.6% of the variance were extracted from the

student IPIP data (the loadings shown in Table 1) by PCA and subjected to varimax rotation. All

10 Extraversion items loaded over 0.3 on the same factor, as did all the Emotional Stability items.

Nine of the Agreeableness items loaded on the same factor, whilst one item (‘‘I make people feel at

ease’’) loaded highest with the Extraversion items. The 10 Conscientiousness items loaded together, with 3 of the items having lower secondary cross-loadings (1 item loaded onto two other

factors). Nine of the Intellect items had their highest loading on the same factor (with 1 lower

cross-loading); ‘‘I spend time reflecting on things’’ loaded highest with the Agreeableness items,

with a smaller loading on the Intellect factor.

6.1.2. Volunteer panel

The overall MSA was 0.80, and all individual itemsÕ MSA were above acceptable levels. The

scree plot suggested the extraction of 5 factors, accounting for 47.9% of the variance. This was

conducted, with varimax rotation, and the item loadings are shown in Table 1. The 10 Emotional

Stability items loaded highest on the same factor. All the Intellect items loaded together, as did the

Extraversion and Agreeableness items, with 1 Intellect, 1 Extraversion and 2 Agreeableness items

having a lower cross-loading of >0.3. Nine of the Conscientiousness items loaded together (1 item

had lower cross-loadings on 2 other factors), whilst one item (‘‘I make a mess of things’’) loaded

highest with the Emotional Stability items.

6.1.3. LBC1921

The overall MSA was 0.85, and all individual itemsÕ MSA were above acceptable levels. The

scree plot suggested the extraction of 6 factors, accounting for 45.2% of the variance. This solution is available from the authors on request. A further PCA was conducted to determine whether

a 5-factor structure also described the data effectively. The 5 factors extracted accounted for

41.1% of the variance, with the varimax-rotated item loadings shown in Table 1. The 10

322

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

Table 1

Rotated IPIP item loadings in 3 samples

Component

E

A

S

E1

E2

E3

E4

E5

E6

E7

E8

E9

E10

A1

A2

A3

A4

A5

A6

A7

A8

A9

A10

C1

C2

C3

C4

C5

C6

C7

C8

C9

C10

ES1

ES2

ES3

ES4

ES5

ES6

ES7

ES8

ES9

ES10

I1

I2

I3

I4

V

.71

.66

.63

.60

.70

.65

.71

.54

.57

.68

.06

.13

.12

.10

.00

.19

.22

.25

.22

.51

.01

.32

.17

.03

.09

.01

.01

.04

.11

.03

.11

.10

.24

.20

.16

.01

.09

.07

.17

.19

.08

.04

.20

.11

L

.68

.66

.60

.81

.64

.58

.75

.70

.75

.70

.22

.16

.24

.03

.17

.00

.31

.11

.08

.45

.07

.03

.20

.04

.06

.01

.08

.03

.07

.22

.09

.03

.05

.10

.21

.19

.01

.07

.01

.07

.07

.08

.11

.02

S

.44

.68

.47

.72

.51

.67

.50

.50

.38

.71

.32

.21

.09

.15

.44

.00

.48

.21

.18

.23

.01

.06

.04

.19

.11

.09

.14

.10

.12

.08

.08

.05

.07

.09

.16

.14

.16

.16

.14

.08

.13

.22

.16

.17

C

V

.09

.08

.21

.01

.18

.18

.10

.07

.02

.01

.51

.50

.46

.69

.63

.42

.68

.34

.55

.10

.07

.12

.33

.01

.02

.01

.03

.10

.10

.03

.04

.18

.29

.17

.18

.25

.08

.19

.06

.05

.10

.10

.20

.39

L

.15

.15

.35

.02

.23

.24

.16

.12

.04

.11

.56

.58

.45

.80

.66

.57

.63

.70

.80

.54

.09

.01

.03

.07

.07

.02

.06

.37

.06

.04

.06

.06

.18

.03

.09

.08

.10

.13

.24

.07

.13

.08

.19

.02

ES

S

.30

.11

.57

.05

.43

.14

.46

.20

.22

.04

.14

.50

.16

.53

.11

.52

.22

.60

.47

.57

.17

.09

.30

.06

.27

.17

.37

.18

.29

.38

.00

.23

.14

.17

.09

.15

.07

.05

.11

.03

.02

:34

.12

.42

V

.02

.04

.20

.03

.06

.03

.03

.18

.09

.13

.04

.04

.21

.16

.02

.19

.07

.18

.05

.18

.52

.55

.38

.54

.67

.67

.61

.47

.75

.54

.08

.04

.02

.06

.14

.08

.14

.10

.13

.04

.03

.01

.21

.16

L

.02

.02

.05

.08

.08

.03

.06

.03

.04

.06

.03

.15

.01

.02

.05

.17

.18

.13

.03

.07

.53

.71

.50

.26

.63

.68

.66

.49

.68

.53

.00

.12

.16

.01

.14

.12

.04

.07

.00

.06

.15

.02

.17

.08

S

.13

.08

.02

.04

.10

.19

.07

.20

.21

.02

.28

.01

.32

.14

.26

.11

.21

.17

.17

.07

.44

.68

.41

.57

.45

.66

.46

.54

.40

.31

.13

.09

.05

.04

.06

.08

.25

.21

.18

.15

.02

.05

.06

.03

I

V

.03

.02

.16

.04

.01

.07

.00

.11

.04

.10

.00

.04

.15

.06

.01

.05

.05

.01

.16

.11

.10

.07

.10

.39

.06

.01

.18

.19

.02

.01

.73

.58

.57

.60

.37

.66

.75

.75

.70

.72

.00

.16

.15

.07

L

.10

.02

.29

.05

.02

.16

.19

.01

.04

.17

.00

.05

.27

.04

.02

.02

.09

.08

.04

.16

.11

.05

.03

.45

.15

.10

.18

.30

.07

.01

.75

.69

.68

.69

.66

.65

.69

.77

.65

.78

.04

.16

.18

.07

S

.07

.06

.25

.18

.19

.05

.20

.17

.14

.24

.03

.02

.09

.14

.11

.21

.00

.03

.15

.22

.07

.04

.05

.22

.13

.13

.05

.17

.00

.09

.71

.60

.68

.58

.71

.76

.61

.65

.62

.69

.14

.16

.27

.10

V

.05

.09

.04

.18

.09

.08

.15

.06

.17

.11

.12

.17

.29

.10

.21

.24

.06

.02

.08

.01

.22

.11

.34

.16

.11

.01

.05

.07

.04

.22

.04

.06

.04

.06

.08

.03

.02

.07

.12

.10

.57

.60

.46

.49

L

.14

.03

.03

.08

.13

.12

.13

.06

.19

.11

.20

.04

.15

.10

.08

.07

.03

.14

.15

.13

.08

.13

.16

.01

.12

.14

.03

.00

.04

.28

.09

.04

.13

.11

.07

.13

.05

.04

.03

.03

.61

.65

.53

.63

.07

.08

.01

.00

.17

.11

.08

.16

.14

.01

.14

.15

.16

.06

.06

.07

.05

.15

.12

.10

.26

.13

.31

.09

.01

.12

.23

.01

.17

.36

.05

.12

.03

.11

.03

.02

.08

.05

.15

.05

.63

.47

.56

.39

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

323

Table 1 (continued)

I5

I6

I7

I8

I9

I10

.28

.22

.16

.02

.21

.29

.18

.12

.11

.17

.22

.20

.04

.34

.01

.11

.13

.08

.16

.12

.03

.07

.43

.05

.06

.17

.05

.12

.31

.05

.26

.10

.25

.01

.31

.20

.13

.02

.16

.13

.09

.08

.23

.04

.14

.12

.01

.13

.05

.23

.15

.14

.09

.02

.04

.04

.14

.06

.21

.06

.03

.04

.15

.09

.26

.01

.01

.13

.09

.02

.13

.01

.54

.53

.60

.72

.34

.51

.57

.63

.55

.58

.37

.60

.66

.43

.46

.50

.38

.67

Note. S = student sample, V = Volunteer Panel, L = LBC1921, E = Extraversion, A = Agreeableness, C = Conscientiousness, ES = Emotional Stability and I = Intellect. Numbers denote the order in which the IPIP items appear in

Goldberg (2001).

Loadings over .3 are shown in bold.

Emotional Stability items loaded onto the same factor. For Extraversion, Conscientiousness and

Intellect, 9 of the items had their highest loading on the appropriate factor (with 3, 2 and 3 items

having lower cross-loadings of >0.3, respectively). The items loading on the ÔwrongÕ factor had a

smaller loading on the appropriate factor. Six of the Agreeableness items loaded together, with a

further 3 which referred to an interest in others (such as ‘‘I am not really interested in others’’)

loading highest with the Extraversion items and the final item (‘‘I insult people’’) loading highest

with the Conscientiousness items.

In each sample, the factor structure appears to conform closely to that reported by Goldberg

(2001), with only minor discrepancies. As such, scale scores were produced for each of the 5 factors, by summing the appropriate 10 items. Table 2 shows the internal consistencies in the 3 samples. These were all acceptable to high, the lowest being 0.72. The mean scale scores in each of the

3 samples are presented also.

6.1.4. Age differences in IPIP scale scores

As the same factors were scored in the 3 samples, the data were combined in order to assess age

differences. The data were split into 3 age groups: early adulthood, which included all participants

up to the age of 30 (men: mean age 21.9 years, sd = 2.4, range 17.8–29.0 years; women: mean age

21.4 years, sd = 2.3, range 17.8–29.8 years); middle adulthood, which consisted of those over 30 and

under 65 (men: mean age 47.8 years, sd = 11.1, range 30.0–64.9 years; women: mean age 49.8 years,

sd = 10.3, range 30.0–63.7 years); and late adulthood, which was all participants over 65 although

the mean age was around 80 (men: mean age 80.5 years, sd = 2.2, range 66.9–81.0 years; women:

mean age 79.7 years, sd = 3.8, range 65.1–83.2 years). The mean scores for the 5 factors are shown

in Table 3. The mean scale levels were compared using an ANOVA, with sex also included in the

analysis. There was a significant main effect of sex for the Agreeableness, Emotional Stability and

Intellect means (F(1,842) = 52.9, 6.9 and 4.8 respectively, p < 0.05). Women have significantly higher

Agreeableness scores, and lower Emotional Stability and Intellect means compared with the men.

The main effect of age group was also significant for each of the factors. Extraversion was significantly higher in early adulthood compared with middle and late adulthood (p < .01 and 0.001

respectively); the middle and late groups did not differ significantly. The early adulthood group

were significantly lower in Agreeableness than the middle and late adulthood groups (p < 0.05

and .001 respectively), and the middle and late groups did not differ. All groups were significantly

different with regard to Conscientiousness (p < 0.01), such that the late group had the highest level,

followed by the middle adulthood and then the early adulthood groups. The early and middle

324

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

Table 2

Means and internal consistencies for IPIP factors

Factor

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Conscientiousness

Emotional

Stability

Intellect

Group

Student (N = 201)

Volunteer (N = 207)

Male

(N = 90)

Male

(N = 61)

Female

Total

(N = 111)

25.2 (7.2) 24.1 (7.0) 24.6 (7.1)

0.87

28.4 (4.8) 30.9 (4.8) 29.8 (5.0)

0.72

22.1 (6.9) 22.5 (6.4) 22.4 (6.6)

0.80

21.8 (7.2) 19.6 (7.7) 20.6 (7.5)

0.85

28.3 (5.9) 25.9 (5.4) 27.0 (5.8)

0.77

LBC1921

Total

Female

(N = 146)a

21.2 (8.7) 22.5 (8.3)

29.6 (6.4) 33.0 (5.5)

26.7 (6.6) 26.9 (6.1)

21.5 (8.3) 20.8 (8.3)

27.5 (6.0) 27.4 (5.9)

22.1 (8.4)

0.90

32.0 (6.0)

0.85

26.8 (6.2)

0.79

21.0 (8.3)

0.89

27.4 (5.9)

0.79

Male

Female

Total

19.9 (7.7) 21.2 (7.3) 20.7 (7.5)

0.84

29.8 (5.0) 33.2 (4.8) 31.8 (5.2)

0.76

28.6 (6.1) 28.8 (6.1) 28.7 (6.1)

0.77

24.8 (8.5) 23.9 (7.9) 24.2 (8.1)

0.87

23.9 (6.0) 23.4 (5.8) 23.6 (5.9)

0.73

Note. Means and standard deviations (in parenthesis) are shown in the top row for each factor.

Internal consistencies (CronbachÕs alphas) are shown in italics.

LBC1921 male N = 192 for Extraversion, Agreeableness and Intellect, 193 for Conscientiousness and 190 for Emotional

Stability; LBC1921 female N = 268 for Extraversion, 269 for Conscientiousness, 270 for Intellect, 271 for Emotional

Stability and 273 for Agreeableness.

a

N = 145 for Agreeableness and Conscientiousness.

adulthood groups did not differ significantly on their level of Emotional Stability, however, the late

adulthood group had a significantly higher level than the 2 younger groups (p < 0.001). The result

was similar for Intellect; however, in this case, Intellect was significantly lower in late adulthood

(p < 0.001), and did not differ significantly from early to middle adulthood.

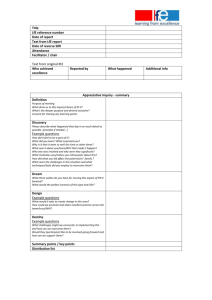

6.1.5. Correlations between measurement instruments

Table 4 shows the internal consistencies for the factors from the 3 questionnaires completed by

the Volunteer Panel. These are all high in the NEO-FFI, the lowest value being 0.79. For the

EPQ-R Short Form, the CronbachÕs alphas for Extraversion and Neuroticism are high; however,

the Psychoticism and Lie Scales are lower (0.56 and 0.66 respectively). The associations between

the scale scores of the different measures are shown in Table 5. The IPIP-NEO Extraversion correlation is 0.69 (p < .01), whilst the IPIP-EPQ and NEO-EPQ Extraversion correlations are

r = 0.85 and 0.76, respectively (p < 0.01). Concerning the Emotional Stability/Neuroticism scale

scores, the IPIP-NEO, IPIP-EPQ and NEO-EPQ correlated r = 0.83, 0.84 and 0.85, respectively (p < 0.01). The negative direction of the IPIP associations is due to the fact that this is

scored towards the emotionally stable pole, as opposed to the emotionally labile pole in the

NEO and EPQ. The IPIP-NEO Agreeableness correlation is r = 0.49 (p < 0.01). The Conscientiousness scale scores from the IPIP and the NEO correlated r = 0.76 (p < 0.01). The 5th factors

of the IPIP and NEO (Intellect and Openness respectively) correlate r = 0.59 (p < 0.01).

Associations were examined within each of the measures. For the EPQ, no internal correlations

were above 0.3. The Extraversion and Agreeableness factors of the IPIP correlate r = 0.35

(p < 0.01). None of the other factors correlated higher. With the NEO, Neuroticism correlated

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

325

Table 3

Mean IPIP scale scores by age group

Factor

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Conscientiousness

Emotional

Stability

Intellect

Age group

Early adult (N = 178)

Middle adult (N = 162)

Male

(N = 78)

Male

(N = 55)

Female

Total

(N = 100)

Total

Female

(N = 107)a

Late adult

Male

Female

Total

25.4 (7.6) 24.3 (7.1) 24.8 (7.3) 21.7 (8.0) 21.9 (8.5)

28.3 (4.7) 30.9 (4.6) 29.8 (4.8) 29.5 (6.2) 32.5 (6.1)

21.6 (6.7) 22.5 (6.6) 22.1 (6.6) 26.7 (6.1) 26.6 (6.0)

21.8 (8.3) 20.0 (7.7) 21.6 (7.3) 21.0 (7.5)

31.5 (6.3) 29.8 (5.2) 33.2 (4.8) 31.9 (5.2)

26.6 (6.0) 28.5 (6.2) 28.4 (6.2) 28.5 (6.2)

22.0 (6.7) 18.6 (7.3) 20.1 (7.2) 21.0 (8.5) 20.2 (8.3)

20.5 (8.4) 24.7 (8.5) 24.0 (7.9) 24.2 (8.1)

27.9 (5.7) 26.8 (5.1) 27.3 (5.4) 28.5 (6.1) 26.6 (6.0)

27.2 (6.1) 24.0 (6.1) 23.9 (6.0) 23.9 (6.0)

Note. The age groups are defined as follows: Early = up to 30 years old (mean = 21.6 years, sd = 2.4), Middle = from 30

to 65 years old (mean = 49.1 years, sd = 10.6), and Late = 65 years and above (mean = 80.0 years, sd = 3.3).

Standard deviations are shown in parenthesis.

Late adult male, N = 204 for Emotional Stability, 206 for Extraversion, Agreeableness and Intellect and 207 for

Conscientiousness; Late adult female, N = 313 for Extraversion, 314 for Conscientiousness, 315 for Emotional Stability

and Intellect and 318 for Agreeableness.

a

For Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, N = 106.

above 0.3 with both Extraversion and Conscientiousness (r =

p < 0.01).

0.42 and

0.31 respectively,

6.1.6. Joint PCA of the IPIP, NEO and the EPQ scales

The scale scores for the IPIP and the NEO-FFI, plus the EPQ-R Short Form Extraversion and

Neuroticism scales, were analysed by PCA (the EPQ Psychoticism and Lie Scale were excluded as

no corresponding factors exist in the IPIP and NEO). The overall MSA was 0.74 and all scale

scores MSA were above acceptable levels. The scree plot suggested the extraction of 5 factors

accounting for 85.9% of the variance. The loadings in Table 6 show that the 1st rotated component is described by the Neuroticism/Emotional Stability scale scores, the 2nd by the Extraversion

scores, followed by Conscientiousness, then Openness/Intellect and finally Agreeableness. No substantial cross-loadings were observed.

7. Discussion

The results of the current study are encouraging with regard to the IPIP 50-item Big-Five factor

markers. In the 3 samples the 5-factor structure proposed by Goldberg has been confirmed, with

only minor deviations from the expected item loadings. The 5 IPIP scales have high internal consistencies comparable to those previously cited (Goldberg, 2001). Cross-sectional changes with

age are reported for the scales for the first time, and these generally follow the patterns seen in

previous work using alternative inventories.

326

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

Table 4

Mean scale scores for the IPIP, NEO-FFI and EPQ-R questionnaires in the Volunteer Panel

Factor

Questionnaire

IPIP

Male

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Conscientiousness

Emotional

Stability/

Neuroticism

Intellect/

Openness

Psychoticism

Lie Scale

NEO-FFI

Female

Total

21.2 (8.7) 22.5 (8.3) 22.1

0.90

29.6 (6.4) 33.0 (5.5) 32.0

0.85

26.7 (6.6) 26.9 (6.1) 26.8

0.79

21.5 (8.3) 20.8 (8.3) 21.0

0.89

Male

(8.4) 26.3 (7.6)

EPQ-R Short

Female

Total

26.7 (7.3)

26.6

0.85

(6.0) 29.9 (5.9) 34.8 (5.9) 33.4

0.80

(6.2) 32.6 (7.1) 33.4 (6.5) 33.2

0.85

(8.3) 20.8 (10.1) 21.9 (10.2) 21.5

0.92

(7.4)

(6.7)

–

–

–

(10.2) 4.8 (3.6) 5.2 (3.5) 5.1 (3.6)

0.86

–

31.3 (6.8)

0.79

–

–

–

–

–

Total

(6.3)

32.1 (5.9)

–

Female

6.3 (4.1) 7.1 (3.7) 6.9 (3.8)

0.89

–

–

–

27.5 (6.0) 27.4 (5.9) 27.4 (5.9) 29.3 (8.2)

0.79

–

–

–

–

–

Male

–

–

–

2.1 (1.9) 1.7 (1.5) 1.8 (1.6)

0.56

4.2 (2.5) 4.8 (2.3) 4.6 (2.4)

0.66

Note. Blank cells denote no corresponding value for the scale.

Emotional Stability is an IPIP factor, whilst Neuroticism is the ÔequivalentÕ factor (negative pole) in the NEO-FFI and

EPQ-R.

Intellect is the 5th IPIP factor, whilst Openness is the 5th NEO-FFI factor.

Factor scores can range between 0 and 40 for the IPIP, 0 and 48 for the NEO-FFI, and 0 and 12 for the EPQ-R.

Means and standard deviations (in parenthesis) are shown in the top row for each factor.

Internal consistencies (CronbachÕs alphas) are shown in italics.

For all means, N = 207 (61 male, 146 female), except IPIP A and IPIP C where N = 206 (61 male, 145 female).

The IPIP Big-Five factor markers correlate highly with the appropriate scales of the NEO-FFI

and the EPQ-R, providing concurrent validity for the IPIP. The associations are particularly high

for N/ES, E and C. With regard to Intellect and Openness, it is unsurprising these factors are related to a smaller degree (Goldberg, 1992), although still at 0.59. The IPIP Intellect factor seems

more reliant on items assessing ideas and imagination, whilst NEO Openness items appear slightly

broader in their scope, encompassing willingness to try new experiences.

In the current study, mean levels of Extraversion and Intellect decrease with age, whilst Agreeableness, Conscientiousness and Emotional Stability increase. These cross-sectional changes with

age are similar to those noted in previous research with other 5-factor inventories (McCrae et al.,

2000; Srivastava, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2003), providing further evidence for the concurrent

validity of the IPIP. It is often stated that personality changes little after the age of about 30

(McCrae et al., 2000); however, significant differences were noted with Emotional Stability and

Intellect in late adulthood. The reasons for this are still unclear and it might be due to a combination of actual changes in personality, as well as cohort differences.

Goldberg (2001) states that all the IPIP items are preliminary, and are to be modified when necessary. The current studyÕs findings suggest a number of possible item alterations to improve the

reliability of the IPIP 50-item Big-Five factor markers. These are available from the authors on

1

1. IPIP E

2. IPIP A

3. IPIP C

4. IPIP ES

5. IPIP I

6. NEO E

7. NEO A

8. NEO C

9. NEO N

10. NEO O

11. EPQ E

12. EPQ N

13. EPQ P

14. EPQ L

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

–

0.35**

0.02

0.25**

0.27**

0.69**

0.20**

0.02

0.30**

0.17*

0.85**

0.31**

0.03

0.06

–

0.17*

0.14*

0.12

0.41**

0.49**

0.17*

0.12

0.19**

0.42**

0.06

0.27**

0.16*

–

0.16*

0.03

0.18*

0.08

0.76**

0.23**

0.21**

0.07

0.16*

0.16*

0.28**

–

0.01

0.35**

0.32**

0.21**

0.83**

0.05

0.23**

0.84**

0.11

0.21**

–

0.17*

0.09

0.07

0.04

0.59**

0.26**

0.01

0.26**

0.06

–

0.26**

0.26**

0.42**

0.04

0.76**

0.37**

0.06

0.00

–

0.15*

0.25**

0.24**

0.22**

0.21**

0.33**

0.20**

–

0.31**

0.12

0.10

0.23**

0.20**

0.38**

–

0.05

0.28**

0.85**

0.09

0.19**

–

0.16*

0.09

0.23**

0.12

–

0.27**

0.06

0.04

–

0.08

0.20**

–

0.15*

Note. E = Extraversion, A = Agreeableness, C = Conscientiousness, ES = Emotional Stability, I = Intellect, N = Neuroticism, O = Openness,

P = Psychoticism, L = Lie Scale.

For all correlations, N = 207, except those with IPIP A and IPIP C where N = 206.

*

p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

Table 5

Associations between the IPIP, NEO-FFI and EPQ-R Short Form factors

327

328

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

Table 6

Loadings for the IPIP, NEO and EPQ scale scores

Component

1

EPQ Neuroticism

IPIP Emotional Stability

NEO Neuroticism

EPQ Extraversion

IPIP Extraversion

NEO Extraversion

IPIP Conscientiousness

NEO Conscientiousness

IPIP Intellect

NEO Openness

NEO Agreeableness

IPIP Agreeableness

2

0.93

0.93

0.91

0.11

0.16

0.24

0.08

0.16

0.00

0.06

0.24

0.06

3

0.18

0.11

0.19

0.93

0.90

0.83

0.03

0.04

0.20

0.02

0.04

0.37

4

0.08

0.06

0.17

0.02

0.08

0.18

0.93

0.92

0.09

0.18

0.03

0.14

5

0.04

0.02

0.00

0.12

0.14

0.01

0.10

0.03

0.90

0.86

0.11

0.04

0.00

0.16

0.06

0.14

0.08

0.17

0.06

0.08

0.06

0.24

0.87

0.78

Note. Loadings over 0.3 are shown in bold.

request, and have been forwarded to Goldberg. Whilst the current study provides concurrent validation for the IPIP Big-Five factor markers, Goldberg (1999) points to a lack of studies comparing different inventories to assess concurrent validity. With the information reported in the current

study, this next stage in the validation is now possible.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Christine Braehler, Sarah Chalmers, Helen Fletcher and Ruth

Turner for their assistance in distributing the IPIP to the student sample, and collating the

responses. Alan Gow holds a Royal Society of Edinburgh/Lloyds TSB Foundation for Scotland

Studentship. Ian Deary is the recipient of a Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award.

References

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., de Vries, R. E., Di Blas, L., et al. (2004). A six-factor structure of

personality-descriptive adjectives: Solutions from psycholexical studies in seven languages. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 86, 356–366.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO five-factor

inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1999). Reply to Goldberg. In I. Mervielde, I. J. Deary, F. de Fruyt, & F. Ostendorf

(Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe (Vol. 7, pp. 29–31). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Deary, I. J., Whiteman, M. C., Starr, J. M., Whalley, L. J., & Fox, H. C. (2004). The impact of childhood intelligence

on later life: Following up the Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 86, 130–147.

Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the Psychoticism scale. Personality and

Individual Differences, 6, 21–29.

A.J. Gow et al. / Personality and Individual Differences 39 (2005) 317–329

329

Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five Factor Structure. Psychological Assessment, 4,

26–42.

Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwith, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of

several Five-Factor models. In I. Mervielde, I. J. Deary, F. de Fruyt, & F. Ostendorf (Eds.). Personality psychology

in Europe (Vol. 7, pp. 7–28). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Goldberg, L. R. (2001). International Personality Item Pool. Web address can be obtained from authors.

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2003). Personality traits (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. Jr., (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Personality and

Individual Differences, 36, 587–596.

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Ostendorf, F., Angleitner, A., Hrebickova, M., Avia, M. D., et al. (2000). Nature over

nurture: Temperament, personality, and life span development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78,

173–186.

Paunonen, S. V., & Jackson, D. N. (2000). What is beyond the Big Five? Plenty! Journal of Personality, 68, 821–835.

Saucier, G., & Goldberg, L. R. (2002). Assessing the big five applications of 10 psychometric criteria to the development

of marker scales. In B. De Raad & M. Perugini (Eds.), Big five assessment (pp. 29–58). Seattle, WA: Hogrefe &

Huber.

Srivastava, S., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2003). Development of personality in early and middle

adulthood: Set like plaster or persistent change? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1041–1053.