WMJ 02 2015 - World Medical Association

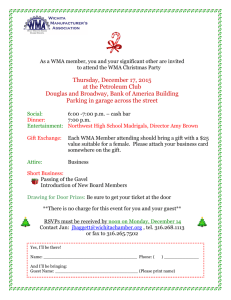

advertisement