Say Sí, Oui, Ee, Yee, `A-ha, Da, Jee/Ji, Haa(n), Ja, Jeje, Ye(s), Yo!

advertisement

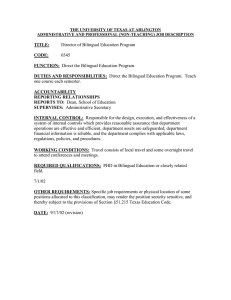

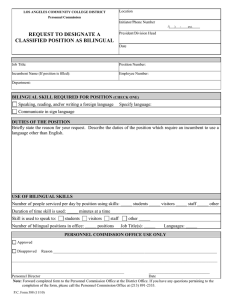

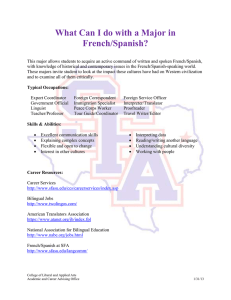

Perspectives J A N UA RY – F E B R UA R Y 2013 A P U B L I C AT I O N O F T H E N AT I O N A L A S S O C I AT I O N F O R B I L I N G U A L E D U C AT I O N Say Sí, Oui, Ee, Yee, ’A-ha, Da, Jee/Ji, Haa(n), Ja, Jeje, Ye(s), Yo! 6,000 Voices Alive and Strong! PLUS: Asian Parents’ Perceptions Toward Bilingual Education Duncan Tonatiuh’s Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote: A Migrant’s Tale Revitalizing the Aanaar Saami Language in Finland Reach Thousands of Bilingual Education Professionals! Perspectives is published in six issues each year, according to the following schedule of publication/mailing date: Issue 1: January/February Issue 2: March/April Issue 3: May/June Issue 4: July/August Issue 5: September/October Issue 6: November/December Advertise in NABE’s Perspectives! Perspectives, a publication of the National Association of Bilingual Education, is read by nearly 20,000 educators and administrators. These readers possess significant purchasing power. Many are responsible for procuring the full range of educational materials, products, and services for use in linguistically and culturally diverse learning environments. To reserve your space, simply fill out the contract (available online at http://www.nabe.org/publications.html) and fax it to 240-450-3799. Call 202-450-3700 if you have any questions. Take advantage of this great opportunity to increase your revenue and advertise in Perspectives! A Full page B&W 7.5" x 10" B 2/3 page B&W 4.875" x 10" C 1/2 page B&W 7.5" x 4.875" D F E 1/3 page B&W 2.25" x 10" or 4.875" x 4.875" 1/4 page B&W 3.5" x 4.875" G Full page Color No Bleed: 7.5" x 10" or Bleed: 8.625" x 11.125" (trims to 8.375" x 10.875") Live content 1/4" from trim All advertising material must be received in the NABE office on the 15th of the month prior to the issue date. For example, for the May/June issue, ad materials are due by April 15. Perspectives Advertising Rates Full Page B&W (A)............... $850 2/3-Page B&W (B)................ $700 1/2-Page B&W (C)................ $550 1/3-Page B&W (D or E)........ $425 1/4-Page B&W (F)................ $375 Full Page Color Ad* (G: Inside Covers Only) ..... $2,000 *Please call for availability of inside cover color ad space Save with multiple insertions! 2-3 insertions: 10% off 4-5 insertions: 15% off 6 insertions: 20% off Contributing to Perspectives GUIDELINES FOR WRITERS NABE's Perspectives is published six times a year on a bimonthly basis. We welcome well written and well researched articles on subjects of interest to our readers. While continuing to address issues facing NABE members, Perspectives aims to meet the growing demand for information about bilingual education programs and the children they serve. It is a magazine not only for veteran educators of Bilingual and English language learners but also for mainstream teachers, school administrators, elected officials, and interested members of the public. Articles for Perspectives must be original, concise, and accessible, with minimal use of jargon or acronyms. References, charts, and tables are permissible, although these too should be kept to a minimum. Effective articles begin with a strong “lead” paragraph that entices the reader, rather than assuming interest in the subject. They develop a few themes clearly, without undue repetition or wandering off on tangents. The Perspectives editors are eager to receive manuscripts on a wide range of topics related to Bilingual and English learner programs, including curriculum and instruction, effectiveness studies, professional development, school finance, parental involvement, and legislative agendas. We also welcome personal narratives and reflective essays with which readers can identify on a human as well as a professional level. Researchers are encouraged to describe their work and make it relevant to practitioners. Strictly academic articles, however, are not appropriate for Perspectives and should be submitted instead to the Bilingual Research Journal. No commercial submissions will be accepted. TYPES OF ARTICLES Each issue of Perspectives usually contains three or four feature articles of approximately 2,000 – 2,500 words, often related to a central theme. Reviews are much shorter (500 – 750 words in length), describing and evaluating popular or professional books, curriculum guides, textbooks, computer programs, plays, movies, and videos of interest to educators of English language learners. Manuscripts written or sponsored by publishers of the work being reviewed are not accepted. Book reviews and articles should be emailed to: Dr. José Agustín Ruiz-Escalante jare21@yahoo.com Columns are Asian and Pacific Islander Education and Indigenous Bilingual Education. (If you have other ideas for a regular column, please let us know.) These articles are somewhat shorter in length (1,000 – 1,500 words, and should be emailed to one of the editors below: Asian and Pacific Islander Education Dr. Clara C. Park: clara.park@csun.edu Indigenous Bilingual Education Dr. Jon Allen Reyhner: jon.reyhner@nau.edu PREPARING ARTICLES FOR SUBMISSION Manuscripts to be considered for the May/June issue must be received by April 15. Manuscripts to be considered for the July/August issue must be received by June 15. Reference style should conform to Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (5th ed.). Articles and reviews should be submitted electronically to NABE Editor, Dr. José Agustín Ruiz-Escalante at jare21@yahoo.com in a Microsoft Word file, 11 point, Times New Roman, double-spaced. Be sure to include your name, affiliation, e-mail address, phone and fax numbers. Photographs and artwork related to the manuscript are encouraged. Please include the name of the photographer or source, along with notes explaining the photos and artwork, and written permission to use them. Photographs should be submitted as separate TIFF, or JPEG/JPG files, not as images imported into Microsoft Word or any other layout format. Resolution of 300 dpi or higher at actual size preferred, a minimum pixel dimension of 1200 x 1800 is required. (Images copied from a web page browser display are only 72 dpi in resolution and are generally not acceptable.) When in doubt, clean hard-copy images may be mailed for scanning by our design staff. Perspectives Published by the National Association for Bilingual Education EDITOR DR. JOSÉ AGUSTÍN RUIZ-ESCALANTE, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS – PAN AMERICAN ASSOCIATE EDITOR DR. MARÍA GUADALUPE ARREGUÍN-ANDERSON, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT SAN ANTONIO ASIAN AND PACIFIC ISLANDER COLUMN EDITOR DR. CLARA C. PARK, CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY-NORTHRIDGE INDIGENOUS BILINGUAL EDUCATION COLUMN EDITOR DR. JON ALLAN REYHNER, NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIVERSITY DESIGN & LAYOUT: Contents ■ Cover Story Say Sí, Oui, Ee, Yee, ’A-ha, Da, Jee/Ji, Haa(n), Ja, Jeje, Ye(s), Yo! 6,000 Voices Alive and Strong! Anita Pandey.................................................................................................... 5 ■ Columns & Articles WINKING FISH Asian Parents’ Perceptions Toward Bilingual Education Fay Shin, Ph.D., California State University, Long Beach.................................... 11 PRINT AND EDITORIAL POLICY Readers are welcome to reprint noncopyrighted articles that appear in Perspectives at no charge, provided proper credit is given both to the author(s) and to Perspectives as the source publication. All articles printed in Perspectives, unless written by an Association staff person or a member of the current NABE Executive Board of Directors, are solely the opinion of the author or authors, and do not represent the official policy or position of the National Association for Bilingual Education. Selection of articles for inclusion in Perspectives is not an official endorsement by NABE of the point(s) of view expressed therein. Duncan Tonatiuh: Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote: A Migrant’s Tale Reviewed by: Ellen Riojas Clark, Ph. D. & Melony Davis, 5th grader................... 13 Revitalizing the Aanaar Saami Language in Finland Jon Reyhner, Northern Arizona University.......................................................... 14 ■ Departments Letter from the President........................................................................................ 4 Contributing to Perspectives - Guidelines for Writers.......................................2 Are you a is a tax-exempt, nonprofit professional association founded in 1975 to address the educational needs of languageminority Americans. N AT I O N A L O F F I C E : 8701 Georgia Avenue, Suite 611 member? Membership in NABE includes a subscription to Perspectives, and so much more. Visit nabe.org to renew or start your new memberhip today! Silver Spring, MD. 20910 Telephone: (240) 450-3700 Fax: (240) 450-3799 www.nabe.org J A N U A R Y – F E B R U A R Y 2 0 1 2 ● V O L U M E 3 5 , I S S U E 1 Letter from the President NABE EXECUTIVE BOARD 2 0 1 2 - 2 0 1 3 Eudes Budhai NABE Board President Dear NABE members, We are living in a time of change! The pressure our education system is faced with today is unparallel. We are experiencing the implementation of the National Standards, new leader/ teacher evaluations, and new assessments with limited resource. As we move forward, our districts are experiencing a decrease in funding and a tax cap that will impact teaching and learning. Yet, many are yielding great results on the backs of our children and educational system. NABE encourages all members to be certain that they speak with their local affiliates, advocacy groups, politicians, and parents to ensure that change occurs in the best interest of children. First, the test of time will provide us with evidence if the implementation of the CCSS is appropriate for all children. We have argued that a gradual approach with sufficient support and resources will ensure “buy in” and progress monitoring towards student growth measures. Subsequently, a simultaneous tying of CCSS and teacher/leader evaluation has resulted in a culture of agony and uncertainty. Therefore, it should be noted, that NABE does not disagree that change is great, but will only strive when planned efficiently and without force. We have requested USDOE and individual States to continue advocating for funding that increase and maintain the pipeline for bilingual/second language teachers. This is especially true if there is a concerted effort to address the needs of ELLs/Bilingual Learners both through academic support and enrichment. The research on Bilingual Education exists with overwhelming evidence of successful pedagogical practices and continues to prevail. Please accept my sincere appreciation for the unconditional assistance you have provided NABE. This support enhances our programs and increases the capacity of teachers to meet and exceed the needs of ELLs/ Bilingual Learners. Your commitment is demonstrated by your participation in NABE activities and your enthusiasm to support nominees running for the Board of Directors. This year we have positions available in the Eastern, Central and Western Regions. Thank you for joining the new online voting that took place on May 10, 2013. NABE is moving into the 21st century to improve our communication with our members and expedite the process to fulfill our obligations to its stakeholders. Please place our 43rd Annual NABE Conference, Bilingual Education: Sailing to Academic and Personal Success in a Multilingual and Multicultural World! on your calendar coming next February 13-15, 2014 in San Diego, California. Visit www.nabe.org for updates and becoming a member to receive our Weekly ENEWS, our Scholarly Online Magazine NABE Perspectives and our two professional journals, Bilingual Research Journal (BRJ) and NABE Journal of Research and Practice (NJRP). Our affiliates and SIGs will continue hosting conferences, webinars, and great opportunities for networking across the nation and we hope that everyone takes advantage of these opportunities. Sincerely, Eudes Budhai, President National Association of Bilingual Education Board of Director 4 NABE PERSPECTIVES ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 PRESIDENT Eudes Budhai Westbury Public School District 2 Hitchcock Lane Old Westbury, NY 11568 W: (516) 874-1833/F: (516) 874-1826 ebudhai@westburyschools.org VICE PRESIDENT José Agustín Ruiz-Escalante, Ed. D. UT Pan American 3740 Frontier Drive Edinburg, TX 78539 W: (956) 381-3440/H: (956) 289-8106 jare21@yahoo.com TREASURER Leo Gómez, Ph. D. H: (956) 467-9505 lgomez2@aol.com SECRETARY Dr. Josie Tinajero, Dean College of Education The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX 79968 W: (915)-747-5572/F: (915)-747-5755 Tinajero@utep.edu PARLIAMENTARIAN Minh-Anh Hodge, Ed. D. Tacoma School District P.O. Box 1357 Tacoma, WA 98401 W: (253) 571-1415 mhodge@tacoma.k12.wa.us MEMBER-AT-LARGE Rossana Ramirez Boyd, Ph.D. University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle#310740 Denton, TX 76203 W: (940)-564-2933/C: (940)-391-4800 Rossana.boyd@unt.edu MEMBER-AT-LARGE Yee Wan, Ed. D. Santa Clara County Office of Education 1290 Ridder Park Drive, MC237 San Jose, CA 95131-2304 W. (408) 453-6825 Yee_wan@sccoe.org MEMBER-AT-LARGE Julio Cruz, Ed. D. Northeastern Illinois University 5500 N. St. Louis Chicago, IL 60625 H: (773) 369-4810 jcruzr@aol.com MEMBER-AT-LARGE Mariella Espinoza-Herold, Ph.D. Northern Arizona University P.O. Box 5774 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 W: (928)-523-7141/F: (928)-523-9284 Mariella.herold@nau.edu PARENT REPRESENTATIVE LTC. Jose Fernandez H: (407)-412-5189/C: (407)-394-6848 ltcjfernandez@gmail.com EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Santiago V. Wood, Ed.D. W: 240.450.3700/F: 240.450.3799 C: 954.729.4557 svwood@bellsouth.net COVER STORY Say Sí, Oui, Ee, Yee, ’A-ha, Da, 1 Jee/Ji, Haa(n), Ja, Jeje, Ye(s), Yo! 6,000 Voices Alive and Strong! Anita Pandey, Professor and Coordinator of Professional Writing at Morgan State University “The world is richer than it is possible to express in any one language” – Ilya Prigogine, Nobel Prize-winning scientist) Is Language Our Birthright? A is for Asia, Africa, America, & B for Bangladesh International Mother Language Day (February 21) is a UNESCO-sanctioned celebration of linguistic freedom (SkutnabbKangas, 2000) and, by extension, of cultural diversity. It represents official recognition of i) language as a cultural treasure (individual and societal) and ii) of individuals’ inalienable right to speak the language(s) of their choosing. Yet, as with most democratizing events, its birth was also preceded by bloodshed. Some might be shocked to hear that many in Bangladesh lost their lives on this day in 1952, when they protested a language law by the President of what was then Pakistan (i.e., prior to Bangladesh’s secession). Unlike in India, shortly after India and Pakistan were divided into two countries at midnight, on August 14, 1947— following what was perhaps the bloodiest holocaust in the history of the modern world—President Jinnah declared that Urdu2 would be the national language of the newly formed Pakistan. The predominantly Bengali-speaking residents in the eastern part of the country mobilized their intellectuals and organized a Language Movement in a bid to make Bengali the state’s official language. To this end, on Feb. 21, 1952, a large group assembled to stage a peaceful protest. The police were called in and fired not just tear gas but bullets, as well, killing several, including four university students. In 1970, after Bangladesh won independence from Pakistan, it declared February 21 a national holiday—to commemorate those who had lost their lives, and citizens’ right to speak their mother tongue(s). Hence was born Language Matyr Day in Bangladesh and, in 1999, as a tribute to this vocal (Bangla) effort, International Mother Language Day, a global celebration of lesser known or minority languages everywhere, and a powerful message of the value and sanctity of one’s mother tongue or primary language (Pandey, 2010). “Ekushey February,”3 the Bengali term for this national celebration of Bangladesh’s language victory, is a day of poignant “emotional significance” in Bangladesh, “the only nation in the world to have fought for and won its independence on the basis of preserving the right to speak its own language” (Khalid, 2013). Not surprisingly, the name of the nation echoes this birthright; Bangla refers to Bengali, the shared “bhasa” or language, while desh (from Sanskrit, and inherited in Hindi and other immediate offspring) refers to county or nation. J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 ★ NABE PERSPECTIVES 5 Shaheed Minar (i.e., Freedom Tower or Symbol), a commemorative memorial that many now term the Language Movement Memorial was built in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, to celebrate this nation’s monumental linguistic victory. It is the site of multiple language-centered celebrations every year. For instance, on Feb. 21, 2013, the richness of Bangla/Bengali is celebrated through poetry/songs, music, and book fairs, featuring the art and writing of Nobel Laurette Rubindardnath Tagore (1913) who was writing poetry as an eight-year-old in Calcutta, India, and whose literary and linguistic contributions are known the world over. Celebrated, too, among other Bengali literary artists and film-makers are the inspiring works and close to 4,000 songs of Kazi Nazrul Islam (dubbed a Rebel poet), a Bengali-speaking activist in the Indian independence movement. Kazi-ji4 incorporated the Moghal ghazal style into Bengali music, yielding a new genre. He was invited by the government of Bangladesh to spend his final days in Bangladesh. Let us turn our attention to the south, to Africa, where innocent children who were protecting their right to learn in Zulu in an apartheid South Africa were massacred. On June 16, 1972, just six years after the birth of Bangladesh and 24 years after several of its intellectuals were killed while fighting for Bangla, some 176 Zuluspeakers—including many children—were gunned down in Soweto for peaceably protesting the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction. As we pause to think of the sacrifices these students and many others made—to ensure that indigenous Africans could hold 6 Shaheed Minar (i.e., Freedom Tower or Symbol), a commemorative memorial that many now term the Language Movement Memorial was built in Bangladesh’s celebrate this nation’s monumental linguistic victory. capital, Dhaka, to on to their language and Bangladeshis could freely use Bengali, the thread that united her people—we are reminded of the linguistic apartheid frequently practiced back then, in different parts of the world, and how even today, many peoples are linguistically imprisoned and/or punished for using their heritage tongues. C is for Canada, Cherokee, and Choctaw; D for Dominican (Republic) On the other side of the world, namely, North America, and in Central and South America, thousands of native American populations were also forced (by mostly English and Spanish-speaking colonists) to stop speaking their languages or risk being physically assaulted or killed. Some 20 years earlier, in October, 1937, for instance, Dominican President Trujillo (known also as El Presidente, El Jefe or the Boss) ordered the mass execution of an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Haitians in a five-day period now termed the Parsley Massacre, one of the worst cases of linguistic warfare and genocide known to date. Those who could not pronounce the Spanish term for parsley (perejil) to his soldiers’ satisfaction were assumed NABE PERSPECTIVES ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 to be Haitian, and promptly put to death (Dove, 1983). Throughout North America, from Canada, to the U.S.A., and Mexico, many languages—and their associated cultural capital, including the Cherokee’s printing press—were confiscated, and their language rights seized or violated. Hundreds of indigenous languages were endangered almost overnight. Over half of the native American languages in use in 1492, for instance, have vanished. While an estimated 90% of Cherokees were literate by 1830—in the sophisticated syllabary that was widely used in pre-colonial America for over 100 years—fewer than half were literate 100 years later. Similarly, in Mexico, while an estimated 60% of Mexicans spoke an indigenous language in 1820, only a mere six percent could do so by the end of the 1900s (Sánchez, 2011). Ten years ago, the government of Mexico finally recognized the need to protect its indigenous languages. Some argue that these belated advocacy efforts (e.g., by the National Institute of Indigenous Languages) are too little and too late. In the case of German and other-language speakers in post World War I-U.S.A., if one did not speak just English, one risked being fined up to $25 (Pandey, 2012) or being beaten or thrown down the stairs. In an interview on Miz.Communication.com (a Memphis-based cable TV show) commemorating native American languages and cultural beliefs, storyteller and magician Autumn Morning Star5 shared how her grandfather was beaten for using his language, and how her grandmother safeguarded “the magic words” and “whispered” them to her in her childhood, igniting in her a passion for Chocktaw and Blackfoot, also termed Siksika (ᓱᖽᐧᖿ), and the cultural secrets embodied in these heritage codes. In Puerto Rico, Taino Indians and their language(s) were quickly exterminated and replaced with Spanish. One wonders if the coqui, the island’s verde frog that legend says pours its heart out for its lost love, sings an ode to her people, who have been silenced forever. When the U.S. imposed English on its newly acquired colonies, including Puerto Rico, Hawai’i and the Philippines, educational failure was inevitable; for example, in Puerto Rico alone, an estimated 84% of children dropped out by third grade (Crawford, 1999, qtd. in Pandey, 2012). E is for English & Enough English! (or not Only English) To the north (in Canada) and down south, all the way from Africa to Australia, the colonists forced their language, most often English, on indigenous populations. Native children were frequently kidnapped from their families in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—in the guise of so-called attempts to “civilize” and “educate.” The forced use of English alone in many religious schools, as in the case of Australia (see Rabbit-Proof Fence, 2002), and lack of tolerance for other languages is a classic example of linguistic dictatorship. The continued use of such practices in immigrant nations like the U.S., where nobody can lay claim to the land—or to a single language—reminds us of our primary responsibility to our children. The right to use any language(s) one chooses to is a basic entitlement (i.e., freedom) every individual should be permitted to enjoy, particularly since the U.S. Constitution does not single out any one language as the official or national language. Denying students access to their (home) language, as we know, only prompts underachievement or educational failure. Not surprisingly, by 1969, approximately 75% of Cherokee children had dropped out of school (Pandey, 2012). Even today, in Africa and elsewhere, students are frequently reprimanded for using the “vernacular,” as it is termed. I recall how my classmates in S. West Nigeria would be fined up to 25 kobo every time they were caught speaking “Yoruba” and “Pidgin.” Such policies not only wipe out languages, they destroy entire cultures and civilizations and send the (questionable) message that other languages—and cultures—are unimportant. Ironically, racial minorities are some of the firmest opponents of minority dialects and languages. This is hardly surprising, given that many have negative labels like “non-Standard English” that suggest that they are somehow lower in status (see Kiley, 2013; Pandey, 2013, 2005), prompting many to distance themselves from these varieties. Ignoring or putting an end to use of the mother tongue could cause other problems, including: ◗◗ ◗◗ Misdiagnosis and undue pressure on the part of students who speak other languages to perform in English-dominant or English-only schools. These often result in low self-esteem or identity crises, and generally lead to a high drop out rate—all of which bode badly for a nation with a predominantly-aging population that is dependant on this generation. More often than not, second dialect speakers and dual language learners/DLLs are assumed to have special needs. This is an example of misdiagnosis. Some children might conform to or display traits commonly associated with specific “special needs.” Not long ago, the Washington Hispanic (Aug. 26, 2011 issue) reported a case of misdiagnosis in Arlington County, VA, considered one of the best school districts in the country. In 2011, this school district apparently spent over $18K per child. The story was titled “Mis hijos no son retardados” (i.e., My children are not retarded). When you cut out the mother tongue— in a bid to supposedly accelerate mastery of English or another “second” language, you end up with catastrophes, as in Arizona. In this English-only state, “English language learners,” as these students are often described—arguably an ideologically loaded term which elevates and prioritizes just English—students in whose homes English is not the primary language are forced to take four hours of English a day. Arizona’s goal is to transition these students to just English as quickly as possible (i.e., to essentially eliminate the home language), typically within a year, or two at most—when, in fact, research shows that students need a minimum of five years (and ideally seven) to master academic language. One student described this approach as “four times 0.” Contrast this with pre-World War-USA which successfully provided other-language or bilingual education to her children—and that too, in multiple languages—all across the country. We must make every effort to stop failing our children. Use of the home language and a systematic, math-andscience-facilitative language-building-blocks approach (Pandey, 2012) could be just the solution needed. H is for Hindi (हिन्दी) and I for India In India, home to some 800 languages, for example, English, one of the two official languages is frequently emphasized over and above Hindi in (reading-writing-based) schooling and other literacy venues, as depicted in the Bollywood movie EnglishVinglish (Shinde, 2012). Interestingly ever since the advent of corporate American outsourcing, print-based advertising in India has begun to pump a new brand of English, namely, American English—and American products—in India’s bazaars, malls (that house American “maal,” the Hindi term for high-priced—mostly U.S. products—in demand), restaurants, and homes (Pandey, forthcoming). Ironically, Sanskrit, the mother language of Hindi—and also of Latin and Greek from which English eventually sprung—donated to English the numbers zero (0) through nine (9),6 the basis of math and science and hundreds of key words still used today, including sugar, and identity-signifying terms like name (from naam(a)), atma, kismet, mother/mata, and father/pita (Pandey, 2012). Yet, today, the globalizing and/or so-called modernizing role and functions of English—bringing India closer to outsourcing and other international opportunities—and the U.S. closer to the world’s largest middle class (estimated at 250 million and rapidly growing) explains why even spoken Hindi is now being marketed through the written medium of English (Pandey & Scott, 2013). An example follows. A McDonald’s (print) ad in India shows four beverages (two fruit-based, alongside a frappé mocha and a frappé caramel). Next to them is the following courtship or date-like invite “Hamaari treat. McDonald’s aaye aur enjoy kare.” Below this appears the distinctively French word McCafé7 and the logo “I’m lovin’ it” beneath the infamous yellow arches. The English renditions of the following collaboration-stipulating and invitational spoken Hindi words: hamaari, aaye, aur and kare (our, come on over, and, and let’s), as J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 ★ NABE PERSPECTIVES 7 opposed to their original Devangari versions (हमारी आये और करे) is noteworthy. At least two reasons account for the use of just Roman script in this ad: i. a purposeful attempt to appeal to or cap- ture the interest of the English-dominant Indian youth, an increasing number of whom can speak but cannot flawlessly read or write written Hindi, and ii. the use of English and English-like Hindi is a linguistic indicator of globalization and the place of English as the default tongue and script of international items or things pardesi (i.e., not desi or Indian) in India—which are elevated linguistically and more highly priced and valued. A third possible reason for this could be its cross-religious and cross-national sell-ability or functionality, so-to-speak. For example, in neighboring Pakistan, where Urdu is spoken—or even in India where Urdu and Hindi co-exist, since spoken Hindi and Urdu are very similar, the use of English script fro both languages would widen the market and cater to both Hindi and Urducomprehending or speaking audiences. For Indians everywhere, English-Vinglish was one of the first Bollywood movies to creatively mix devanagari and English scripts (and not just the spoken forms) and, more importantly, to put them on the same level in a constitutionally bilingual nation, which has lately been depicted as a land of global—or should I say “globalized” opportunities (Pandey, 2011). This is a monumental linguistic feat and a welcome symbolic gesture in what is arguably a hyper-globalized multilingual landscape—one in which the words “treat” and “enjoy” are relative newcomers, since Indian hospitality means that treats are commonplace. McDonald’s attempt to reciprocate (this don’t-ask, just invite and share form of hospitality) by extending a “treat” to Indians sells. When we consider the fact that the equivalent terms for “enjoy” in most Indian languages are negative and connote laziness and undue wastage, Oppa Gangnum style (i.e., the kind associated with the rich and famous or spoiled), we can be sure the English word “enjoy” is inviting. 8 Perspectives from the North, Sud (Spanish), Occidente (West/ Italian), & पूरव ् (East/Hindi) Politics and language rights aside, each language variety weilds social significance within its realm of use. Indeed, every communicative medium has its treasures—special terms, unique gestures, and hard-totranslate or non-translatable meanings (see Pandey, 2012) for concepts considered sacred or important in each culture, as outlined in Table 1. We must develop in our children a keen sense of curiosity that prompts them to want to discover these special gifts languages encapsulate. What better way to inventory or capture culture, for instance, than to map variations and differences in language use? Yet, many teachers, administrators, and policy makers continue to denigrate (individuals’) languages and to demoralize and fail thousands of students— all across the United States. Cultural & Language Enhancement: Sample Classroom Prompts To learn, students have to feel comfortable and welcome. A common language bridges cultural, gender, geographic, racial, social class, and other divides. Conscious integration of other languages in the classroom and through out-of-class language and culturalinfusion projects is not merely advisable but essential, since the home language is the best way to bridge the school house and the home. Inviting students and families to share fables, family stories (which they could bilingualize using their creativity), paired hand counting and jump rope (also termed “skipping”) and group songs, rhymes, and birthday songs in other languages are other ideas. Teachers could explore the possibility of loaning families a camcorder for a day and/or assigning tasks that involve digital clips from smart phones to which families have access. Examine what you get back, or random segments, and use these to create family portfolios, supplementing other assessment tools you use to monitor student progress. Displaying children’s and staff members’ names in different languages/ scripts at children’s desks or on class doors, in the hallway and in other visible spaces at school also sends a loud and clear message— that all are welcome. NABE PERSPECTIVES ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 Additional collaborative classroom activities that would simultaneously connect the home and school house follow: 1. Invite your students and their families to create an alphabetic book of languages spoken or used at their school or in their neighborhood. They could make a book of languages for each continent or include a representative listing of languages (and dialects) from different geographic areas. This could be a cross-grade activity, with age-appropriate tasks for each student. Students could also include—in this book or another—key words and or expressions in each language they inventory (e.g., common greetings, apologies, and ways of expressing gratitude, and sympathy). You could invite them to share copies with their families and administration, as well as in the form of a newsletter or with Perspectives and other media outlets that would further validate and publicize their work (with the world) and garner feedback that they could use to revise, edit, and expand (e.g.,languagebuildingblocks. com). The number of languages students list and/or the artwork or layout/ organization could determine the prizes received. In other words, adding a competitive twist or incentive will very likely further motivate students. They could collaborate on the illustrations/artwork, as well, and use technology tools to create the finished product. This could then be collectively edited (another language-andliteracy-enhancing task) and uploaded on the school’s Website and/or other sites or venues, so that students and families would feel validated and take greater pride in their work. Schools could compare language notes and publicize the number of languages (recorded) in use on their premises. Those that record the largest number of languages, for instance, could label themselves or be labeled as the (2nd) Most International School in 2013, or some such. On February 21 or on another date designated as “Language Awareness Day/Week/Month, students could wear ribbons coinciding with the number of languages or language families at their school. They could wear accessories (e.g., ties, belts, headbands), and clothing (e.g., multilingual t-shirts or polo shirts they design) sporting diverse language scripts. These forms of public awareness and Table 1: Examples of Linguistic Treasures Language Treasure: Form, Term or Expression, & Significance Closest Translation &/or Example Sanskrit & its immediate offspring (Hindi, Punjabi, Gujarati) Swastika: nonverbal & visual: auspicious blessing Mark (tikka) of health (swast) in the four directions of the world Yoruba Prostrate/Prostration: Nonverbal greeting by males & female bowing. Greeting; communicates respect for elders. E ku ile (spoken): ile = home/house Asko; “a cheeky response to a question one finds unnecessary or insulting; it’s like saying, “are you asking me that” or “who are you to ask that question?” (Ibid). “greeting extended to an older adult or group of people you meet at home” (Oluseyi Emiola, personal communication). Maori Noses make contact (via a quick rub or touch) Conventional meet-and-greet for one’s fanau (i.e., family, non-biological, too) Hindi, Punjabi, Gujarati & other N. Indian languages Touching the feet of an elder or person in a position of power (generally by those young(er): nonverbal Respect marker and greeting or leave-taking expression. Term: paer choona (Hindi) or Gujarati pagge lago —touch/hug or literally fall on the feet). Arabic: subsequently borrowed into Urdu & many other languages Haraam(i) Unclean animal (e.g., pig) and/or person Hindi & Urdu Paap(i); many instinctively touch the books or people they unintentionally disrespected (through their nonverbal behavior) and then touch their foreheads to express their reverence and elevate them—much like the holy trinity gesture Punishment-conducive/sinful; e.g., Desecrating books by placing them on the floor or touching them with your feet—symbolically demoting them or lowering their value. Japanese kyoikumama Mothers who push their children to excel in school, expecting perfect scores/grades Mandarin Use of numbers to convey added meanings; e.g., 8, 10, or “We sold one hundred & sixty-eight hogs” (Pandey, forthcoming). Rhymes in this tonal language with the word for good fortune/luck, & definite (go), respectively. Hebrew Dafka/davka Multiple meanings, including “between thine eyes” (classical), “in your face!” (modern slang), in spite of, and an apology or recognition of an unintentionality act(ion). Ibo Heleo an expression of sadness or sorrow, like Nigerian English “Wonderful!” Shona Pamusoroyi “You say this when you are about to eat, it’s like saying excuse me as a form of respect” (Vanessa Mbedzi, personal communication) Nigerian Pidgin Dash (from Portuguese) Expected gift/bribe (noun & verb) How far? “greeting used among friends to enquire after their welfare, like “how are you doing?” (Oluseyi Emiola) Kpelleh/Guerze/Kpese Kumanlee Multifunctional: means “hello, how you doing? what is wrong with you? or why are you so sad?” and “It can even be used to ask a question” (Morrinah Kwekeh, personal communication). Venda langa (to) control J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 ★ NABE PERSPECTIVES 9 recognition of multiple languages would further inspire students to take pride in their/other languages (i.e., languages they understand, speak or wish to learn). 2. Invite students to interview at least two speakers of other languages and to share two to three words, expressions or gestures that do not have an exact equivalent in English (see Table 1—which you could invite students to extend), and to share what they learned from this experience. It’s a good idea to ask them to provide their contacts’ contact information—for clarification purposes. 3. Invite students to research favorite yet diverse foods and/or musical genres featuring different languages or a mix of languages (e.g., bhangra, bharatanyatam, chiac, ghazal, popular Bollywood, khattak, salsa, makossa, AfroBeat (pioneered by Fela Kuti), juju (created by King Sunny Ade), Taraab, Chaabi, Gnawa, Griha (Moroccon genres), soukous (African/Congolese rumba), Bango, Coptic, Maloya, and Sega.zouk, and so on) that their peers and/or peers’ families periodically or frequently access and to create a multimedia food book or musical (language) fusion theater project that captures diverse senses, including sounds, instruments, and languages/voices. They could then share—verbally or via a reflective write-up, or a combination— what they learned from this exercise. 4. Invite students to co-construct content- specific or age-appropriate stories containing words from more than two language varieties. They could string together rhyming words—with each student supplying a word that phonemically and semantically extends the story line—in haiku mode. An example could be Hola bola Kola: Beyond Goa, a Dr. Seuss style story which borrows a word from Spanish, Hindi/Urdu, and Yoruba, respectively, and translates to “Hello,” Said Kola. The class could collectively pick the title and/or change it to, for example, Kola bola “hola!” and discuss how word order is flexible in Hindi and Urdu, the host language(s). Such conscious cross-language comparisons would serve to further reinforce students’ vocabulary, grammar, and intercultural skills (i.e., beyond Standard English). 10 Directions for Future Research & Concluding Remarks The projects proposed above could be combined. Projects like these are bound to enhance students’ inquiry/researching and their peer and community-collaboration skills, among others—specifically their crosscultural and language awareness or knowhow. At the very least, students and teachers will come away with a greater appreciation for diversity. In turn, language researchers could monitor the impact of these and other multilingual or language-valorizing activities on students’ academic achievement and interpersonal relationships. They could design and test other language-enhancing studies on, for instance, the impact of cross-language reading strategies on all students’ reading comprehension skills and scores (see Pandey, 2012 for additional research projects). All we have to really want is to get to know our students (Bell, 2012). This means taking an interest in their home language(s). Success—in interpersonal skills, vocabulary, math, science, health literacy, intercultural know-how, and a whole lot more—will follow. Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reminds us that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights … and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” When we deny a person their language, we take away their voice. We must excite and ignite critical thinking—artful, culture-specific, variegated, and unparalleled. Only then can we say we are truly global—and at least 6000 voices richer, louder, and stronger. ★ References Bell, D. (2012). Resource Guide to Language Building Blocks. New York: Teachers College Press, p.5. Retrieved from http://www.tcpress.com/pdfs/9780807753552_supp.pdf Khalid, F. (2013). On Feb. 21, Bangladeshis Have Good Cause to Celebrate Int’l Mother Language Day. Retrieved Feb. 21 from http://asiasociety.org/blog/asia/feb-21bangladeshis-have-good-cause-celebrate-intl-motherlanguage-day. Kiley, A. (2013). Expert: Considering Students’ Home Language Could Help School Performance. Milwaukee Public Radio Interview Archive. Retrieved March 20 http://www.wuwm.com/programs/lake_effect/lake_ effect_segment.php?segmentid=10250 Dove, R. (1983). Parsley. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University Press. Grinevald, C. (2007). Endangered Languages of Mexico and Central America. In Endangered Languages, Brenzinger, Matthias (Ed). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 50-86. Pandey, Anita. (forthcoming). “When “Second” Comes First— हिंदी to the Eye?: Sociolinguistic Hybridity in Professional Writing”[Invited chapter] In Writing as Translingual Practice in Academic Contexts: Premises, Pedagogy, Policy, edited by S. Canagarajah. New York: Routledge. _________. (2013). Using mother tongue as building blocks in education. ACEI Radio Interview. Feb. Retrieved March NABE PERSPECTIVES ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 23 from http://acei.org/news-publications/acei-radio.html _________ & Scott, C. (2013). Race to the Future by . . . Worshipping Your Stomach?: Ethicality and Corporate Communication Strategies. Proceedings of the 2013 ABC Conference. _________. (2011). Editor’s Introduction, Professional Communication in the Age of Outsourcing. International Journal of Communication, 21/1: 1-4.Critical Inquiry in Language Studies: an International Journal, Vol. 2 (1). pp. 35-69. _________. (2010). The Child Language Teacher: Intergenerational Language and Literary Enhancement. Manasagangothri, Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages. 405pp. _________. (2005). A Cyber Stepshow: E-Discourse and Literacy at an HBCU.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies: an International Journal, Vol. 2 (1). pp. 35-69. _________. (2002). Director & Host. Miz.Communication. com, Episode 2. September 2001, Memphis cable TV show, channel 17. Sánchez, L. (2011). Mexican Indigenous Languages at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century edited by Margarita Hidalgo. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 15: 422–425. Shinde, G. (2012). English-Vinglish. Retrieved on Feb. 12: http://englishvinglishacademy.com/ Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2000). Linguistic genocide in education—or worldwide diversity and human rights? New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum. Endnotes 1.“Yes” in multiple languages. Invite students to guess or research the source languages. 2. Urdu is very similar to Hindi in the spoken form (see Pandey, 2012). Ironically, it is an artful mix of spoken Hindi, Arabic, Persian and Turkish, and reflects the multiple linguistic influences in the region and the cultural syncretism that defines the Indian subcontinent, specifically northern India and Pakistan today—starting with King Bharat and Ashoka’s language, through the language of the Delhi Sulanate and the Mughal/Moghul Empire. 3.Incidentally, Ekuse,” a Yoruba word, is pronounced similarly and translates to the applause “Well done!” or Congratulations). 4.–ji is an honorific particle appended to the end of names in many Indian languages, including Bengali, Hindi, Punjabi, and Urdu. 5.She is one of fifty Native Americans profiled by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. 6. These (Indian) numbers were eventually introduced to the Western world through the Arabs—hence the label “Arabic numerals.” 7. The Frenchified spellings are noteworthy—very likely intended to give these “treats” a touch of class and increase their perceived fancifulness or upper-class-ness (hence the high price tag). Anita Pandey is professor and Coordinator of Professional Writing at Morgan State University. She was born and raised in Africa—home to two-thirds of the world’s languages. During her childhood years, her family was constantly on the move, so she developed a passion for language(s) early on. She picked up Hindi, English, Yoruba, Hausa, and Nigerian Pidgin in her childhood, and learned French and Spanish as a teenager— primarily from children. This is the subject of her first book, The Child Language Teacher: Intergenerational Language and Literary Enhancement (Mysore: CIIL) which demonstrates the value of sustained family and community engagements. Her most recent book is titled Language Building Blocks: Essential Linguistics for Early Childhood Educators (Early Childhood Education Series) from Teachers College Press http://store.tcpress. com/0807753556.shtml. Asian and Pacific Islander Asian Parents’ Perceptions Toward Bilingual Education Fay Shin, Ph.D., California State University, Long Beach Would Korean, Hmong and Chinese parents of English language learners want their child to be in a classroom where the primary language is being used for instruction? The major controversy regarding the education of our English language learners has traditionally centered on the language and methodology used for instruction. Parent involvement in bilingual education has become both a state and a federal mandate and one which is supported by both legislation and court action. However, parents should always be considered as a major source or foundation for bilingual programs in our public schools. In addition, most of the research on English language learners (ELL’s) are from Hispanic backgrounds (Genessee, 2006). There is a need for research on the development of ELL’s from other major ethnolinguistic groups in the United States. Vietnamese, Hmong, Chinese, and Korean students need to be examined because they are the next most populous groups of minority students in the U.S. Parents have always been crucial in the implementation and maintenance of duallanguage programs (Gandara & Hopkins, 2010). Parents of immigrant children have important roles in second language acquisition, since the first language proficiency will become the foundation on which the second language structure will be built for their children. Furthermore, parental attitudes about the majority culture also affect children’s achievement in the learning of the majority language, and of the majority culture. The use of the native language at home by parents and other family members has proven to be crucial in students’ development of English literacy and preparation for school life (Nieto, 1992). Golub and Prewitt-Diaz (1981) found that teachers were not successfully communicating the values, methods, and outcomes of bilingual education to parents. This study was a synthesis of the findings of three studies investigating whether Hmong, Chinese and Korean parents agreed with the rationale for bilingual education and if they approved of having their children in a bilingual classroom. These studies were unique in that they were done in the context of a theoretical model, and specifically assessed parent opinions of the main theoretical foundations of bilingual education. The research questions were: Do Korean, Hmong and Chinese parents approve of placing their children in a bilingual classroom? Do Korean, Hmong and Chinese parents agree with the underlying principles and rationale for bilingual education? Subjects The sample consisted of 256 Korean parents, 100 Hmong parents and 10 Chinese parents, in California. The Chinese parent study is forthcoming. Preliminary data from the Chinese parents will be discussed. All the parents participating in this study have children in an elementary school. The demographics of the parents varied widely. The majority of the Chinese and Korean parents were highly educated (over 65% had college or graduate/professional degrees) and only a minority of the Hmong parents had college degrees (20%). Methodology The survey was developed by Shin and Kim (1998) in English and translated into the primary languages (Korean and Hmong). The Chinese parent interviews were conducted in English. The survey consisted of 27 questions including demographic information as well as parents’ perceptions and attitudes toward bilingual education. The demographic questions include the length of residency in the United States, the educational level, the socio-economic status, parents’ English proficiency, the language used at home and whether their child is enrolled in an English Language Development program. The questions address parents’ perceptions and attitudes toward the principles of bilingual education. Responses were measured using Likert scale questions with options of strongly J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 ★ NABE PERSPECTIVES 11 agree, not sure, and strongly disagree. The surveys were distributed mostly by classroom teachers to Korean parents via students in the classroom (70% return rate). The Hmong surveys were distributed through both the classrooms and local community organizations (40% return rate). A brief letter explaining the importance and the purpose of the study was distributed along with the survey. These surveys were voluntary and anonymous. It was collected in the similar manner, parents to students and students to classroom teachers. Results and Discussion The results showed mixed results for the first three principles: bilingual education allows children to keep up in subject matter while acquiring English, developing literacy in the primary language is necessary in order to facilitate the acquisition in English, and learning subject matter through the first language helps make subject matter study in English more comprehensible. However, more than fifty percent of the parents agreed that developing literacy in the primary language is important to facilitate the acquisition in English. There was very strong support for the last three principles and advantages of bilingualism. An average of 90% of all the Korean and Chinese parents surveyed agreed that bilingualism can lead to practical, career related advantages, results in superior cognitive development (benefits our intelligence), and was necessary to maintain primary language 12 and culture. This shows that parents are aware and supportive of the advantages of being bilingual, and the importance they place on keeping their primary language and culture. The majority of the parents indicated that they would place their child in a bilingual program if their child was not proficient in English. Seventy percent of Korean parents, 80% of the Chinese parents and 60% of Hmong parents said “yes,” although some parents indicated they were not sure. Only a small minority actually said they would not place their child in a bilingual classroom. Findings and Conclusions The findings of these studies show that there is considerable support for the underlying principles of bilingual education, and only a minority actually opposes placing their children in bilingual education programs. They show a very strong understanding and belief that bilingualism and primary language maintenance is important and advantageous. Over half of the respondents also showed an understanding and approval that literacy transfers. In addition, the findings of this study are consistent with other studies (Gandara & Hopkins, 2010; Hakuta, 1983; Shin & Gribbons, 1996). The fact that these studies involved parents with different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, gives us more confidence about our conclusions. These studies showed that there was powerful support for the rationale for the advantages of bilingualism and maintenance of the primary language culture, and mixed results for the early principles. The majority of the Korean, Chinese and Hmong parents indicated that they would want their children in a bilingual classroom. It is clear from these results that Korean, Hmong, and Chinese parents showed support and strong opinions toward placing their children in a bilingual program and for the rationale for bilingual education. However, if parents are opposed to placing their child in a bilingual classroom, we need to consider many factors. Sometimes parents are misinformed about the program and its goals (we often hear: “I want my child to learn English”), and more often we hear from the very vocal parents which we assume is the voice of all parents Several other studies by Nguyen & Shin (2001) and Shin and Lee (1996) investigated 588 Vietnamese and 100 Hmong NABE PERSPECTIVES ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 elementary and middle school students’ attitudes toward their heritage language and culture. These studies indicated positive attitudes toward heritage language and culture. The results also found positive relationships between attitudes and academic achievement among middle school Vietnamese students. Many parents who enrolled their child in a bilingual classroom, tended to be very satisfied with the program, and were more likely to support bilingual education (Shin and Kim, 1998). In conclusion, parents have an important role in promoting literacy and language in the home and much more research on Asian parents’ language and literacy practices is needed. The fact that new dual language programs are opening across the nation suggests that interest continues to grow for bilingual programs. ★ References Gandara, P. & Hopkins, M. 2010. Forbidden Language: English Learners and Restrictive Language Policies., New York, NY: Teachers College Columbia University Genesee, F., Lindhom-Leary, K., Saunders, W. & Christian, D. 2006. Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press. Golub and Prewitt-Diaz (1981). The Impact of a Bilingual Education Program as Perceived by Hispanic and NonHispanic Teachers, Parents, and Students. Journal of Instructional Psychology 8, 50-55. Hakuta, K. (1983). Bilingual Education in the Public Eye: A Case Study of New Haven, CN. NABE Journal 9, 53-76. Nguyen, A., Shin, F. and Krashen, S. (2001). “Development of the first language is not a barrier to second language acquisition: Evidence from Vietnamese immigrants to the United States” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Shin, F. (2000). Parent attitudes toward the principles of bilingual education and their children’s participation in bilingual programs. Journal of Intercultural Studies. 21 (1). 93-99. Shin, F. and Gribbons, B. (1996). “Hispanic Parent Perceptions and Attitudes of Bilingual Education.” The Journal of Mexican American Educators. 16-22. Shin, F. and Kim, S. (1998). “Korean Parent Perceptions and Attitudes toward Bilingual Education.” Current Issues in Asian and Pacific American Education. Endo, R., Park, C., Tsuchida, J. and Agbayani, A. (Editors). Pacific Asian Press of Covina, CA. Shin, F. and Lee, B. (1996). “Hmong parents and students: What do they think about bilingual education?” Pacific Educational Research Journal. 8(1), 65-71. Dr. Fay Shin is a Professor of ELD, literacy, and bilingual education at California State University, Long Beach and the coordinator of the Asian Bilingual Authorization Credential Program. She co-authored a book with Dr. Stephen Krashen, Summer Reading: Program and Evidence, and developed an ESL–Science program, Journeys-ESL/ELA in the Content Area: Science, which is being used nationwide. Duncan Tonatiuh’s Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote: A Migrant’s Tale Reviewed by: Ellen Riojas Clark, Ph. D. & Melony Davis, 5th grader A lovely book for all, young and old, for all generations in the USA, for all ethnic groups, for literary and artistic types, this is a good all around book. It is written for 6 - 9 year olds but I loved it as did 10-year-old Melony, a fifth grader at Poe Elementary School in Houston, Texas. It is the story of many of the children in our schools whose families have traveled to the North in search of a better life. It is the story of all the struggles suffered by these families in their quest through the fable of rabbits and coyotes. What also captivated my granddaughter and I was the artwork that so dramatically portrayed the story as Melony commented, “the drawings are very good.” The illustrations are not only colorful but also reminiscent of the codices and are done by the talented bilingual and bicultural, Duncan Tonatiuh, the author and the illustrator. A prize winning author, Tonatiuh also wrote two other children’s books Diego Rivera: His World and Ours in 2011 and Dear Primo: a Letter to my Cousin in 2010. We decided to do a joint book review since the voice of the child reader is never included in a review or as Melony put it: “It is written for us, so we should say if we like it or not.” And Melony liked the book very much as did other young children to whom we read the story to hear their reactions. In this lovely picture book, Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote: A Migrant’s Tale by Duncan Tonatiuh, just out this May 2013, the child rabbit is awaiting the return of his father who has gone to the US to work. The family has a party to celebrate the return of the father with typical food and decorations such as papel picado. The fiesta shows animals as musicians playing instruments such as a guitar, a bajo, and an accordion. When he does not return, Pancho, the boy rabbit then sets out to search for his father, packing all his favorite foods, the mole, the beans and rice, such a poignant scene. We liked the illustrations of chilies, corn, onions, tortillas, and avocados, the staples of our food, though aguamiel was not as well known by us. The drawings of the metate, the comal, the tortilla press, and the ollas were realistic and are recognizable parts of our culture. The metaphor of the coyote is made even more dramatic as he wants to eat Pancho because he is still hungry even after eating all of the food brought by Pancho. Melony liked the illustration on that page “I like how it shows the mole still on the coyote face.” The glossary presents the two definitions of a coyote- the animal and the person who is paid to take the immigrants across the border. The illustrations as well as the story reflect the dangers of going through the desert and crossing over into the US. I thought Melony’s comment regarding the following was interesting and we checked it out: “Kids won’t understand this line ‘junked on the riverbank.’ Adults understood the line but kids didn’t understand ‘junked.’ She liked the humor such as when the mother comments in the very last line: “Lets hope it rains, said Mama.” After the father says he might have to leave again if there are few crops due to a drought. For those of us who have not had to face these struggles, the story provokes empathy and understanding for those children who have undergone such experiences. The book provides the opportunity for all children, parents, and teachers to talk about a situation that is real for so many. The epilogue in the book is based on the Author’s Notes that end with dismal statistics: “there are an estimated 1.5 million undocumented children in the US (2011) and 5.5. million children of undocumented immigrants in US schools (2008). We both agree with Tonatiuh”s last statement “… that a lot of these children will relate to Pancho Rabbit” as we did with this book. ★ About the reviewers: Melony and Dr. Clark. Melony loves drawing, acting, and creating so she competes in Odyssey of the Mind, sells Girl Scouts cookies, and sings in choir. Most often, Melony practices the piano and plays with her dog. Dr. Clark is Professor Emeritus in Bicultural Bilingual Studies at UTSA. Areas of research and publications are in teacher student identity and efficacy, bilingual education teacher preparation, and cultural studies. Address correspondence to Dr. Ellen Riojas Clark at Ellen.Clark@utsa.edu J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 ★ NABE PERSPECTIVES 13 Indigenous Bilingual Education Revitalizing the Aanaar Saami Language in Finland Jon Reyhner, Northern Arizona University Marja-Liisa Olthuis, Suvi Kivelä and Tove Skutnabb-Kangas provide a detailed study that gives hope to speakers of severely endangered languages. In Revitalizing Indigenous Language: How to Recreate a Lost Generation (Multilingual Matters, 2013) they document how the Aanaar Saami (AS) in Finland, with only about 350 speakers of their language, were able through the Complementary Aanaar Saami Language Education (CASLE) project from 2009 to 2010 to make significant strides in revitalizing their language. Dr. Olthuis spearheaded CASLE, Kivelä was a student in the program, and Dr. SkutnabbKangas is an internationally known researcher of indigenous language rights and revitalization. The AS are part of the estimated 75 to 100 thousand Saami, most of whom are living today outside their homeland. 14 NABE PERSPECTIVES ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 The “lost generation” of AS in this book’s title are young adults, age 20-39, too old to have taken advantage of the first AS language nest established in 1997 and too young, because of the suppression of the AS language in schools and elsewhere, to have learned it at home as the elder generation did. The CASLE program recruited 17 motivated “young professionals” who showed language-learning aptitude by already having learned at least one second language with a few non-Saami students in program. Funding was found so that these 17 participants could be full time students for one year. For these older students Finnish was used as the language of instruction in first three courses to provide basic knowledge of the AS language. The following nine courses used AS as the language of instruction. To implement the CASLE project, possible funding agencies were identified and approached, potential employers for project graduates were identified, language revitalization efforts worldwide were researched, motivated students were recruited that could be full time language learners for a year, and teaching materials were developed. By careful selection, the project had no dropouts and graduates went on to staff two new AS language nests opened in 2010 and 2011, multi-age AS immersion classrooms, and a media program. The CASLE program provided the 1600 to 1700 hours needed to learn everyday language plus the vocabulary of a student’s chosen profession. Of course to become a real Master of a language takes some 20 years. While the CASLE program was designed to meet the unique needs of the Aanaar Saami and utilize available funding, it has several important aspects that any endangered language community should seriously consider implementing. The CASLE experience reinforces what language activists know about language nests and Master-Apprentice (M-A) language revitalization methodologies. Language nests are described as “backbone of AS revitalization,” a “gentle environment” for language learning, and “the strongest possible revitalization method for children” (pp. 46 & 130). However, for the students the “M-A training was experienced as the most beloved part of CASLE” (p. 80). Twenty-two paid Masters with 5 to 7 hours training usually worked with two students at once, and students had multiple masters. Students were expected to know the basics of the AS language before starting M-A activities. The most common M-A activity was looking at old photos, mostly at the Master’s house. One Master noted in regard to his apprentices’ language learning, “Nobody can deal with it if somebody corrects every word” (p. 88). After their coursework and M-A activities such as fishing, CASLE students had a training period, mostly in the AS language nest or a multi-grade immersion classroom. Hurtles to AS language revitalization remain, including providing spaces outside language nests for young learners to speak AS. However progress is being made both with young and older learners. There is now an AS major at the University of Oulu and students can graduate with masters degree in AS. The authors note that severely threatened languages need to accept second language (L2) speakers and anyone willing to learn the language. The last quarter of the book is a series of 18 “Info Boxes” written by Skutnabb-Kangas that are referred to throughout the rest of the book. She starts with one on criticism of Sweden’s minority policies and practices and ends with one on the Saami language and traditional knowledge. These boxes overview current international and Finnish research on language revitalization and indigenous education. Many of the indignities the Saami have faced including being put in boarding schools and having their language suppressed in Scandinavia are similar to what has happened to colonized indigenous people in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States and elsewhere. In their conclusion the authors note “the reversal of language shift has affected people’s dignity and the way they look at the future” for the better (p. 165). The authors describe many hurtles, especially the lack of AS teaching materials, that had to be overcome in developing the CASLE project and offer valuable insights for anyone interested in language revitalization on how to overcome them. ★ J A N U A RY – F E B R U A RY 2 0 1 3 ★ NABE PERSPECTIVES 15