Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University: How

advertisement

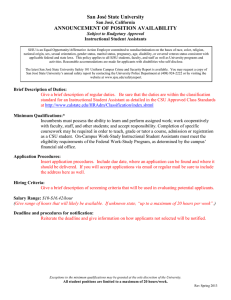

233 ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University: How Do They Use a Joint Library? 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen d fo rp Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen S ,c Introduction op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e abstract: The King Library in San José, California, is a unique combination of academic and public library. It serves the diverse populations of the City of San José and San José State University (SJSU). This article provides analysis of data collected in a study on the concept of “library as place” and SJSU students’ sense of belonging toward the King Library building. This study involved a mixed quantitative-qualitative research approach. In total, 744 students were surveyed. The results show that SJSU students use the library and it is relevant to their needs. Ideas for improvement and creation of services are offered. Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed an José State University (SJSU) is located on 154 acres in downtown San José, California, in the heart of Santa Clara County. As of Fall 2011, the university had 30,236 students and 1,731 faculty on campus. From July 1, 2010, to June 30, 2011, SJSU awarded 4,832 bachelor’s degrees and 2,479 master’s degrees.1 SJSU is part of the California State University system, which—with its 23 campuses, 417,000 students, and 46,000 faculty members—is one of the largest institutions of public higher education in the nation.2 The Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library houses both the main branch of the San José Public Library as well as the SJSU library. It is in this library that both “town and gown” share a facility dedicated to lifelong learning for all members of both the public and the university communities. The building itself houses 1.9 million items, and has eight floors, six classrooms, 36 meeting rooms (2–12 person capacity), four special portal: Libraries and the Academy, Vol. 13, No. 3 (2013), pp. 233–256. Copyright © 2013 by The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD 21218. 234 Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p 3. l1 or ta collections rooms, a Cultural Heritage Center, and a Children’s Room. The majority of these spaces are shared by SJSU and the City of San José communities, which creates a synergy within the building between these two distinct groups, not only offering numerous spaces for interaction but also a large collection of information resources to consult. Since this joint project was the largest of its kind in the country, from the announcement of the endeavor in 1997, the project and the building made groundbreaking news in major library journals.3 Details about the characteristics and philosophy of the project were published by professionals who worked in the library, both before and after the two institutions merged. Christina A. Peterson and Patricia Senn Breivik talk about the different organizations and task forces formed between the City of San José and San José State University in the planning process of the joint-use project. This article mentions the challenges and formation of different joint services.4 Paul Kauppila and Sharon Russell describe both the City of San José and the San José State University communities, the size of the collections, the planning process, and the management structure during the development of the merger.5 After the library opened in 2003, a number of articles were published to describe the new organization. Breivik, Luann Budd, and Richard F. Woods discuss characteristics of human resources, institutional differences, and the co-management teams of the newly formed library. The authors observe that a joint project is more like a marriage, in that the institutions “remain two separate entities, each contributing different strengths and talents to the partnership.” 6 Peterson gives a comprehensive report about building designs and use of the space after the first year of operation. The San José State University and the San José Public Library share the same space to engage the diverse community. Peterson also describes how the building is a lifelong learning space.7 In addition to these materials, authors from outside the King Library have given their point of view on the innovative institution. John N. Berry offers his insight regarding the “Gale/Library Journal Library of the Year 2004,” and George Plosker provides details about funding the development of the project. Kirsten L. Marie compares a similar joint project to the SJPL/SJSU merger, the “biggest library west of the Mississippi,” where NSU (a private university) joined with BCPL (Broward County Public Library) located in Broward County, Florida.8 Moreover, various authors published articles about the design and organization of specific joint services within the King Library. Richard F. Woods describes the different stages of planning for a joint Information Technology Services.9 Danianne Mizzy, Kauppila et al., and Harry Meserve all discuss the formation of the merged Reference Services and Reference Collection. The task of combining all of these services and collections proved quite challenging because of the disparate missions and patrons each institution serves.10 The study discussed in this article focuses solely on the student population of San José State University and their use of the joint academic-public library on the university campus. These students constitute a unique population that the authors felt was worthy of significant study. Library use by the San José public patron is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, SJSU students’ use of the King Library is compared to studies—discussed in the following literature review—that look at student use of more traditional academic libraries at other universities. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University 235 Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 Michel De Certau defines places as spaces that have been transformed by the people who use them. He asserts that “space is a practiced place.”11 Further researchers extend this analysis and try to understand how this transformation actually happens. 12 Two basic needs must be met in order for such a transformation to take place. First, the public space needs to be safe for individuals; and second, there need to be smaller niches within the space that individuals can adapt to meet their private needs. For example, a student can adapt a study carrel for her learning process, without anyone bothering her and without getting in anyone’s way. It then becomes a private space within the larger, secure place of the library.13 The concept of space/place was extrapolated to encompass the library in the early 2000s, when the library’s paradigm shifted. Specifically, the academic library shifted from a “storehouse” of books or a “book-centered” space to a “learning-centered” space.14 Characteristics of this learning-centered space include a greater emphasis on the cognitive processes of students, such as the importance of information commons, and also on the social interactions of students, for example, the addition of cafes and coffees shops within the library, study/meeting rooms, and areas where eating and higher noise levels are acceptable.15 In The Library Study at Fresno State, students were asked to identify features that would make a library ideal for their use. Given the opportunity, students put forward ideas that would make the library a place with various spaces that would meet nearly all their needs: “quiet/loud, serious/social, and individual/group.”16 Scott Bennett states that in “their behavior, students…have affirmed quite decidedly there is no contradiction in thinking of the library as both a social and a studious place.”17 Many studies supply information about how students use the library, but Karen Antell and Debra Engel offer a look at how faculty members use the library building. They found that there is a generational divide between older and younger faculty members. While all scholars they surveyed used the library’s resources for research purposes, the oldest and youngest faculty members were more likely use the space for writing papers, with those in the middle working at the tables in the library less often. The researchers hypothesized that older scholars would report greater use of the physical space and less use of electronic resources. They were correct in all categories but one—when asked about the physical library’s conduciveness to scholarship, “younger scholars were far more likely than older scholars to make statements reflecting the idea that the physical library is a unique place that facilitates the kind of concentration necessary for doing serious scholarly work.” The authors went on to say that this “seems to indicate that the library building design trend toward including more space for library users and less space for library materials is exactly on target for younger faculty members as well as for students.” 18 The shifting paradigm of the library coincides with the shifting needs of the students and faculty who will be using the library space for years to come. The library space is now seen as collaborative, social, and educational, and these functions must integrate seamlessly with print and electronic material.19 By including electronic material as part of the library’s new role, it becomes clear that the physical space is no longer the limit of the library’s space. David Kohl argues that “we have outgrown that metaphor…we 3. Literature Review 236 Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University Methodology Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p or ta The authors of this study developed a thirty question survey, which can be roughly broken into four sections: demographics, frequency of use, services used, and use of space. Most of the questions on the By including electronic material as part survey were multiple choice, but three requested a written response. of the library’s new role, it becomes The full survey is included in the Appendix of this article, and was clear that the physical space is no londerived from a combination of four ger the limit of the library’s space. instruments. The first was created by one of the authors, Valeria E. Molteni, in a previous study of library as place.22 The second component was an internal instrument created at the King Library by Rebecca Feind, Shannon Staley, and Lydia Collins. This instrument is partially described by Staley, Nicole A. Branch, and Tom L. Hewitt;23 however, the full instrument remains unpublished. The third component of the survey was derived from Antell and Engel’s 2006 article “Conduciveness to Scholarship.”24 The fourth component came from a 2002 article published by Gloria J. Leckie and Jeffrey Hopkins in The Library Quarterly.25 Additionally, the authors designed new questions that specifically addressed the study’s objectives. The final survey instrument distributed to survey respondents was focused toward how a student would use the library, rather than how a member of the public might use the same joint space. The two goals of the study included: 1) identify the actual use of the library as a place by university students, and 2) make recommendations for future services that enhance the students’ use of the library. The study included SJSU graduate and undergraduate students who participated in library instruction sessions given by the authors during the 2010–2011 academic year. The authors are academic liaison librarians who serve departments from a variety of the colleges on campus, including Communicative Disorders from the College of Education; Communication Studies, Political Science, and Public Administration from the College of Social Sciences; Linguistics and Language Development from the College of Humanities and the Arts; and Social Work, Nursing, Nutrition, Food Science, and Packaging from the College of Applied Sciences and Arts. In addition, the authors also provide information literacy sessions for general library instruction initiatives, such as general education English courses required of all students at the university. The survey was administered at the end of the authors’ instruction sessions, and the completion of the survey was voluntary for all respondents. In total, 744 surveys were collected. The questionnaires were distributed to respondents in paper format. The library provides a variety of spaces where instruction may take place, only some of which l1 3. 3. have exhausted the all-encompassing vision of the library [building] as place.”20 Changing needs of patrons require librarians to redefine somewhat their understanding of the library as a place. Technological shifts require that the library serve as a digital space as well as a physical place. As Jeffrey Pomerantz and Gary Marchionini point out, the “most critical element of this space may not be that it is either physical or virtual, but that it is intellectual.”21 237 ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 include computers. Therefore, to assure uniformity in data collection, the authors determined paper format best met the needs of the study. The authors obtained a grant to hire a graduate student familiar with data entry, processing, and analysis. This student entered the survey responses into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and then exported the data to SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). The quantitative data from the multiple-choice questions and qualitative data from the narrative-response questions was then analyzed by the authors. The tool Wordle (http://wordle.net) was employed to analyze word frequency in questions with a written response. Carmel McNaught and Paul Lam employed this tool in two qualitative studies that involved analysis of text and concluded that Wordle “can be a useful research tool to aid educational research.”26 In addition, when Amanda Clay Powers, Julie Shedd, and Clay Hill analyzed chat and e-mail reference answers over a two year period in an academic library, they employed Wordle to study word frequency in their data. 27 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen rp Results and Analysis fo Demographics Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d The first section of the questionnaire distributed to students focused on demographics, and the questions asked about the students’ gender, ethnicity, age, academic major, and class level. These questions assist in determining if the survey population was reflective of the entire university population, which would allow the authors to draw conclusions about students’ overall use of the library and its services. The population of the survey was mainly female (527 female and 217 male, 70.8 percent and 29.2 percent respectively). This data aligns with the characteristics of the general population of the university for the academic year 2010–2011, which was 53.20 percent female and 47.66 percent male.28 The larger number of females in the sample population was because the survey was delivered to several departments with a disproportionately higher female presence, such as Nursing. Data from the SJSU Office of Institutional Research showed that during Fall 2010, the Nursing School had an 85.23 percent female population in its student enrollment, and 89.6 percent of the degrees awarded were to female students for the 2010–2011 academic year. The data related to age was also consistent with the student population for the entire university. The majority of the students were between 18 and 25 years old (67.9 percent), followed by the student group between 25 and 29 years old (14 percent). The next group of 30 to 39 year olds represented 11 percent of the study population, followed by the group of 40 to 49 year olds at 4.4 percent. The last cluster makes up a very small percentage: the students between 50 and 59 years old represent only 2.2 percent and the group of 60 to 69 year olds equal only 0.50 percent of the survey population. This is similar to the whole university, where the average age for undergraduates is 22. 29 When questioned about their ethnicity, students were asked to choose between African American, Asian, Latino/a, White, Other, or were allowed to fill in a line where they could define themselves in another category and describe it. The survey population was predominantly Asian in ethnicity, which coincides with data collected by the university about the overall population on campus.30 238 ub lic at io n ,p or ta l1 3. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University ce pt e d fo rp Figure 1. Gender ac Table 1 di te d an d Academic Majors ye Rank op 1Nursing ,c 2Business ew ed 3Undeclared 4 Health Science Linguistics and Language Dev 5 Nutrition, Food Science and Pkg re vi 6 pe 9 Social Work er 7 8 Child and Adolescent Dev 6.3% 5.1% 5.1% 5.1% 4.0% 3.8% 2.7% Political Science 1.9% s .i ss m 20.0% Occupational Therapy 2.3% 1.7% Th is 12 30.2% Communication Studies 10Psychology 11 MajorPercentage In total, the students in the survey population were from 39 different majors, which spanned all colleges on campus as well as interdisciplinary programs that do not fall under a single designation. These colleges include the College of Applied Sciences and Arts, the College of Business, the College of Education, the College of Engineering, the 239 re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 College of Humanities and the Arts, the College of Science, and the College of Social Sciences. The highest percentage of the sample belonged to the Nursing School (thirty percent), followed by students from the School of Business (twenty percent), and the third largest group comprised students who were undeclared majors. The Nursing School has a curriculum focused on Evidence Based Practice and research, with a specific course (NURS 128) that is pivotal for these topics, and the librarian teaches in all sections of this course. The School of Business also has a high representation in this survey, even though neither of the authors is the liaison for this school. The reason for this is a mandatory upper division 100W writing course, with the goal of developing writing and research skills across all disciplines. The School of Business does not offer its own 100W courses; instead, there are 100W courses in the Communication Studies and Linguistics and Language Development departments targeted toward business students. Both Communication Studies and Linguistics and Language Development are included in the authors’ liaison duties; thus, many business students were included in the survey. The next cluster of majors (between 5.1–1.7 percent) shown in Table 1 comes from schools or departments where the authors are liaisons or areas that have a close relation to those schools or departments. The final cluster of majors (between 1.3–0.1 percent – not shown in Table 1) is from schools or departments other than those where the authors are liaison librarians. Thus, the survey clearly demonstrates that library instruction sessions serve a wide range of disciplines, and many of the courses taught fulfill General Education requirements that are mandatory, regardless of the student’s major. The bulk of library instruction centers around junior level 100W writing courses, so, not surprisingly, the most significant class level in the survey was juniors (36.8 percent), followed by seniors (29.3 percent), freshmen (15.5 percent), graduate students (12.6 percent), and sophomores (4.6 percent). An additional 1.2 percent did not answer this question. Again, the survey maintains some level of consistency with the general SJSU population. The highest concentration of students is juniors and seniors for two reasons. One is due to budget fluctuation and restrictions. During the last three years, SJSU has reduced enrollment for undergraduate (freshmen) and graduate students. The second reason is that, at SJSU, the median to finish an undergraduate degree is six years.31 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen pe er Frequency of Use Th is m ss .i s The second section of the survey focused on frequency of use. The students were asked how long it took them to get from home to campus, how many hours they spent on campus per week, how often and how long they visited the library per week, which days and times they visited the library, and if they came to the library with other people. Asking students how long it took to get from home to the library was significant because this factor could be a potential barrier to use of the building and space. The majority of SJSU students hails from Santa Clara County, and thus commutes to campus. However, all new freshman who graduated from a high school outside of a thirty-mile radius from SJSU are required to live on campus their first year. An estimated 5,000 of the 30,000 students live within walking or bicycling distance.32 The majority of the students surveyed for this study claimed it took less than thirty min- 240 ub lic at io n ,p or ta l1 3. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp Figure 2. Class Level pe er re Figure 3. Frequency of Visit v. Commute Th is m ss .i s utes to get to campus, with 32.3 percent responding that it took less than fifteen minutes and an additional 44.9 percent in the fifteen to thirty minute group. 16.7 percent said it took 31–60 minutes, and only 4.8 percent stated that they commuted more than an hour. Comparing the commute times with the frequency of visits to the library, it became clear that, in general, the shorter the commute, the higher the number of visits to the library. The most significant group of students visited the library in the afternoon (46.5 percent), with a roughly similar number using the library in the mornings (19.9 percent) or evenings (22.8 percent). This changed slightly when compared to the hours that students claim they prefer the library be open, with students choosing evenings as their preferred 241 ub lic at io n ,p or ta l1 3. 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen fo rp Figure 4. Hours on Campus v. Hours in Library Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d hours (34 percent), followed by mornings (27 percent) and afternoons (20.4 percent). An additional 18 percent said they did not know which hours they preferred. When asked how many hours they spend on campus per week, the highest number was in the five to ten hours per week group at 43.5 percent, followed by the ten to fifteen hours group at 21.4 percent. At the lower end of the spectrum were the fifteen to twenty hours per week group (13.3 percent), the 20–25 hours per week group (6.5 percent), and the 25–30 hours per week group (4.3 percent), but there was a slight increase again at the thirty-plus hours per week group with 11 percent. It is possible that students spend less time on campus because they commute home to do more work there, which explains the ever-increasing statistics for electronic resources being accessed remotely. However, when comparing the hours students spent on campus per week with the hours they stayed in the library, it became clear that students were definitely making time in their commuter schedule to spend time in the library. Across all groups, students were most likely to spend one to two hours per week, followed by the thirty to sixty minute group, and then the two to four hours group. The data also revealed that those who spent the least amount of time on campus per week (five to ten hours), were also the group most likely to spend time in the library across all time periods. When asked about days of the week that they visited the library, Monday through Thursday were the most popular with a range of 49.7 percent to 55.2 percent of students choosing those days, which correlates with the amount of classes offered on the SJSU campus. Classes are usually offered on either a Monday/Wednesday schedule or a Tuesday/Thursday schedule. Friday, Saturday, and Sunday showed significantly less usage by students, by a factor of almost two to one. It is unclear, however, if this is simply due to class scheduling or if it is because the library is open fewer hours on Friday through Sunday, and is thus less available for use by students. Students were asked about their use of libraries both before and during their tenure at SJSU. Before SJSU, a majority of students used public libraries (75.8 percent) and 242 ub lic at io n ,p or ta l1 3. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University fo rp Figure 5. Use of Other Libraries re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d school or community college libraries (60.2 percent). While at SJSU, the use of libraries other than the King Library dropped significantly. Many still used public libraries (53.8 percent), and these are specifically their local library branches, since King Library is a joint public-university facility. However, the use of school and community college libraries dropped to only 7.5 percent. The use of other libraries that were not in the first two categories rose sharply from 1.1 percent to 12.9 percent. These may include university libraries in the vicinity of SJSU, including Santa Clara University and Stanford University. Students typically came to the library by themselves (48.7 percent) or with one other person (34.7 percent), with only 15.5 percent coming with two or more people. This contrasts slightly with the activities student claimed they used the library for—shown in the next section—which are the group study rooms that require two or more people in order to use. Of those who did come to the library with other people, it is significant to note that the majority (50.4 percent) stated that these were friends, rather than classmates (22.6 percent). This strongly supports the idea that students consider the library a social as well as a studious space.33 pe er Services Used Th is m ss .i s The third part of the survey focused on the services students use in the library. Students were asked what activities they engaged in while in the library. They were given a chart with 25 different options to choose from, and they could also add their own responses. Students were also asked what possessions they brought with them while using the library building or services. Again, they were asked to choose from a chart or add their own responses. Finally, respondents were asked to identify which services—if any—they used to find their way around the library. Students were allowed to choose more than one option on all of these charts, so there was overlap in the answers. For activities students engaged in, the most popular were conducting research, using a study room, working with a group of classmates, working at a table in the library, s .i ss m Figure 6. Activities in the Library is Th er pe ew ed vi re d di te ye op ,c d an ac d ce pt e ,p io n at lic ub rp fo ta or l1 3. 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen 243 244 ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p 3. l1 or ta and writing a paper. The most significant comments students made in addition to the options on the chart included studying or doing homework, reserving a room for group work, printing papers, and using the library’s access to wireless internet. Several students mentioned taking advantage of the services in the Adaptive Technology Center in the library, which is controlled by the campus-wide Disabilities Resource Center. Of the possessions brought to the library, the vast majority of respondents said they brought a cell phone (95.2 percent), backpack or briefcase (91.3 percent), and writing materials, such as paper, pens, and pencils (92.2 percent). The next cluster of possessions that students brought to the library included a laptop computer (77.8 percent), snacks and/or drinks (76.9 percent), and personal copies of books or journals (73. percent1). Significantly fewer (41.4 percent) claimed they brought library copies of journals or books with them. Possessions students brought with them that were not on the chart can be grouped under several categories, the first being music, iPods, and headphones. Other items mentioned were medication, identification, clothing, and shoes. Materials that assisted with various class assignments were included, from drafts of research papers to course syllabi, copies of homework assignments, and even drafting boards. Multiple students specifically mentioned textbooks, indicating they group these into a category separate from the “personal copies of books” offered as an option in the main question. The library offers a variety of services to assist students in navigating the space, including tours, maps, and guides, and staff who are available to direct students. However, not all students take advantage of these services. When questioned on what combination of methods they used to find their way around the library, the majority opted for self-discovery, with 62.1 percent using a method of trial and error and an additional 39.8 percent using the maps and guides provided by the library. Following that, 22.5 percent responded that they asked a library staff member for directions, 18.5 percent said a friend or classmate showed them around, and 9 percent took a formal tour. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University ,c op Use of Space Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed The largest portion of the survey, fell under the category of “Use of Space.” These questions looked at what places students used most often and had adapted as a personal space within the library. Additionally, it was important to investigate which features of the library students liked the best and least, in order to discover further barriers to use, as well as what the library is currently doing right in terms of the space offered. Students were surveyed on whether they use the library’s physical space and the results were resoundingly positive: 78 percent of respondents said yes, 20.8 percent said no, and 1.2 percent gave no answer. An overwhelming majority (80.1 percent) answered yes to the question about using the library space just to study, work, or relax, without using library resources (such as books, journals, or library computIn addition, 73.7 percent of Students were surveyed on whether they ers). students said they conduct their use the library’s physical space and the research or work on assignments at the library, and the majority of results were resoundingly positive. students (64.1 percent) write part or all of their papers at the library. Also, 76.6 percent of students responded that they use the SJSU library’s electronic resources remotely. 245 Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 When questioned about their opinion regarding the differences between using the library remotely and the physical space, the majority did not answer the question (44.1 percent). Only 33.6 percent found differences between the library services offered electronically and the services offered in the building, and 22.3 percent of the students did not see any differences. Students were also asked about their favorite place to sit while in the library building. They were given nine options to choose from, and they could also add their own responses. Again, students were allowed to choose more than one option, so there was overlap in the answers. The most popular locations for students to sit were a table with chairs (89.1 percent), a study room (60.6 percent), a chair at a computer (39.2 percent) and a lounge chair or sofa (30.6 percent). That each option was selected by multiple students suggests that they are very familiar with the different spaces throughout the library, including special collections (3.4 percent), even with its more restricted hours for use. The majority of students also have a favorite floor (57.5 percent) to use within the library, and the 8th, 7th, 6th, 2nd, and 4th floors proved the most popular. The silent study floors in the library are the 6th, 7th, and 8th, with the bulk of the academic material located there. The 2nd floor holds the majority of the computers students can use, and the 4th floor has the librarians’ offices, as well as a large number of study carrels and tables with chairs. The 3rd floor, which was also popular, but definitely less so than the silent floors, houses most of the material from the public library, which means much of the popular fiction and many foreign language sources. The final set of questions was open-ended and meant to uncover the students’ favorite and least favorite aspects of the library’s space. For two of the responses, the authors used Wordle to create word clouds that made the words mentioned the most often larger than those mentioned less often in the responses. This question was posed to the students: “The King Library is a very particular building in that it serves both SJSU students and the San Jose general community. What is your experience or feeling, as a library patron and student, about this combination?” The answers were mixed. Many of the respondents mentioned the presence of homeless people who make them feel uncomfortable, while others mentioned the diverse community and the space for studying. However, when provided the opportunity to give the best word to describe the library, the response was generally positive. Many students commented on the size of the library, and also that they find it resourceful, convenient, comfortable, clean, and helpful. Regarding the best feature of the library, many comments mentioned the study rooms, and again, the resources, the quiet environment, and the space. Regarding the worst feature, again the presence of homeless people is a strong theme. Students also mentioned that they would like more open hours, more outlets for laptops, and that the library can get crowded. 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen Further Research The authors have presented various aspects of their findings at two conferences, the California Academic and Research Libraries Conference (CARL)34 and the Joint Conference of Librarians of Color (JCLC).35 At CARL, initial findings from the data that formed 246 at io n ,p or ta l1 3. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic Figure 7. Best Feature of the Library re vi Figure 8. Worst Feature of the Library Th is m ss .i s pe er this article were presented; whereas, at JCLC, the demographic information on students’ ethnicities was isolated to compare the use of space and services at the King Library by different ethnic groups on campus. Further study on this aspect of the data is in progress in preparation for publication. Conclusions and Recommendations The initial goals of this study were twofold: to identify the actual use of the library as a place by university students and to make recommendations for future services that would enhance students’ use of the library. To address the first goal, it is important to return to the most important question of this survey. Students use the library – 78 percent of the survey population said so. They 247 Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 use it throughout the day and week; they use the library even when they spend less time on campus. There were some aspects of the library they did not care for, and some suggestions and improvements that can be made, which will address the second goal of the study. However, the overall feedback from the questionnaire was relatively positive. The demographics of the survey population coincide with that of the university on the whole, which allows the authors to draw conclusions that can apply generally to all SJSU students. For both the survey and university populations, the majority of students are female, between 18–25 years old, predominantly Asian in ethnicity, and with the highest concentration of students in the junior and senior class levels. Also, the survey population reflects the fact that SJSU is a commuter campus, with most students spending between five and ten hours on campus. Those with shorter commutes spend more time in the library, and expressed the desire to have the library open during the evenings, presumably when a student who might have a full time job in addition to attending college would have extra time to spend in the library. The majority of students came to the library Monday through Thursday, and they preferred to be in the library during the afternoon. The survey population visited less on Fridays in part because there are fewer classes offered and the library is open far fewer hours, but perhaps also because not having a class on campus on that day deters them from commuting into the library. When on campus, commuter students seek to integrate their student and personal lives. For example, the answers given about the possessions they brought to the library suggest that because they do not have individual spaces on campus, such as a dorm room or personal locker, where they could put items like clothing and medication, they instead carry those along when they come to the library. The survey indicates that the student population is quite familiar with the many spaces available within the library, and they prefer to learn to navigate the building on their own. In addition, they prefer to use and engage the different spaces that were designed for them (academic floors) and show much less of a partiality for the spaces that were designed for the general public. Overall, the survey indicates that students not only use the physical library and the services offered, but that they like the library and find the services relevant to their needs. A few recommendations that can and should come out of this study would include possible solutions to the issues that students brought up, as well as methods to build upon the strengths that students mentioned. Administrators on the academic side of the library have sought out the authors to discuss the results of the data collected and have consulted on several projects to help make improvements within the library for the student population. Students showed a preference for the quiet study floors of the library that host the academic collections, while also frequenting the floor with the majority of computers for patrons to use. This floor is also where the library’s joint academic-public reference desk is located. Students mentioned that they use the library most often for conducting research, using a study room, writing papers, and working at a table and/or with a group of classmates. In many ways, the results of this study confirm that, despite the joint nature of the library, SJSU students still use the library in a similar way to students surveyed in other studies on the academic library as place.36 However, SJSU students expressed in several of the written response questions that they are uncomfortable having to deal with the homeless population. 3. Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen 248 Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p 3. l1 or ta The preferences of the survey population suggest that some computers be made available on the floors with the academic collections that students frequent most often, as well as having a librarian available on one or more of those floors However, SJSU students expressed in to provide research consultations. several of the written response questions In Summer 2012, the library’s Student Computing Service Center that they are uncomfortable having to (SCS) was relocated from the lower deal with the homeless population. level to the 4th floor of the library, which is one of the more popular floors for studying and group work. SCS provides students with laptops and iPads they can check out, troubleshooting for wireless issues on personal laptops, and setting up library database passwords.37 Moving this service has proven very successful for the library, increasing the visibility and usage of the SCS Center. Additionally, in Spring 2013, a group of SJSU librarians launched a pilot project to have roving reference hours throughout the academic floors of the library. These librarians carry an iPad with them, announce their presence to students in the area they are roving, and then students raise their hands if they have a research question. This project is ongoing, but initial results are quite favorable. The creation of a computer lab in the loft space above the enclosed Children’s Room is a developing project on which the authors provided consultation, using the survey data. This is one of the few areas of the open-concept library that is enclosed—an important feature because it has been decided that this space will be for students only. In this respect, the space becomes not just the “learning-centered” space suggested by Scott Bennett and Frieda Weise,38 but specifically a “student-centered” space. In planning this lab, the authors recommended that group study rooms or tables be provided within the space, as well as areas where students can quietly write papers or work on other class assignments. Additionally, the authors advocated for a focus on the academic resources students preferred and a reference desk where research consultations would be provided. The lab opened in Spring 2013, and library faculty and staff are currently collecting data on student use of the space. At this time, the lab is covered as part of the roving reference pilot project to see if this satisfies the reference needs of the area, or if a permanent desk needs to be installed in the space. With a joint-use public and academic space, determining when and how students use the library is complicated. This survey’s data is specifically student data, providing significant information for the university side of the library to work with to prioritize what students might want or need most. 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University Acknowledgements This research was grant funded with a 2010–2011 CSU Research Funds Award Valeria E. Molteni is an Academic Liaison Librarian, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, San José State University, CA; she may be contacted via e-mail at: valeria.molteni@sjsu.edu. Crystal Goldman is the Scholarly Communications Librarian, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, San José State University, San José, CA; she may be contacted via e-mail at: crystal.goldman@sjsu. 249 Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen 3. edu. Enora Oulc’hen is Head of the Music Department, Bibliothèque Publique d’information, Centre Pompodiu, 75197 Paris Cedex 04, Paris, France; she may be contacted via e-mail at: enora.oulchen@bpi.fr. ta l1 3. Appendix ,p or The SJSU King Library and the concept of Library as a place ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n We are conducting a study on the library as a place and how it is used by SJSU students. We would like you to participate in a voluntary, anonymous survey about your use of the King Library. This survey should take no more than 10 minutes for participants to complete. If you feel uncomfortable with any of the questions, you do not need to answer them. The results of this study will be presented at library conferences in 2011. Furthermore, your responses will help us implement future library services and share our ideas with other librarians. About Yourself …. er re vi ew ed 2. Gender Female Male Other ,c op ye di te d an d ac 1. Ethnicity Latina/o African American Asian White Other Do you define yourself in another category? Would you like to describe it? ____________________ Th is m ss .i s pe 3. Age 18–25 25–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 4. How many hours do you typically spend on campus? (Check one) 5–10 10–15 250 Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University 3. l1 ta or ,p 5. Did you use the library before your University experience? If so, what type? Public Libraries School libraries Other types of libraries. Please specify__________________________ Did not use libraries before university experience. 3. 15–20 20–25 25–30 30+ lic at io n 6. Can you speak/read/write in another language? Which one? If yes, answer question 7. If no, skip to question 8. di te ye op vi ew ed ,c B. Level of class standing Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Graduate d an d ac 8. About Your Academic Status…. A. Major: _________________________ Minor: _________________________ ce pt e d fo rp ub 7. Where did you learn your second language? Home School Church Other places. Please specify ________________________________________ re About the Library… Th is m ss .i s pe er 9. How long does it take you to travel from your home to this library by your usual means of transportation? (Please check one) Under 15 minutes 15–30 minutes 31–60 minutes Over one hour 10. During the course of a typical semester, how frequently do you visit the library? 1–2 times per semester 3–4 times per semester 1–2 times per month 3–4 times per month 251 Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen ,p or 3. ta l1 11. How long is your typical library visit? / How long do you typically stay at the library? Under 30 minutes 30–60 minutes 1–2 hours 2–4 hours More than 4 hours 3. 1–2 times per week 3 or more times per week This my first visit to the library ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n 12. What day or days of the week do you usually visit this library? (Please check all that apply) Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday op ye di te d an d 13. What time of day do you usually enter the library? (Please check one) Morning (before noon) Afternoon (noon–5:00) Evening (After 5:00) Don’t know re vi ew ed ,c 14. What hours do you prefer the library to be open? (Please check one) Morning (before noon) Afternoon (noon–5:00) Evening (After 5:00) Don’t know Th is m ss .i s pe er 15. How many people usually accompany you to the library? (Please check one) None One other person Two or more other people 16. If one or more people usually accompany you to the library, are they primarily: Friends Relatives Co-workers/classmates Other 252 Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University 17. Do you use other libraries? Local branch library Community college library Other ,p l1 or ta As you answer the following questions, please think about the physical spaces in which the libraries and collections are housed, rather than the electronic resources available through the library’s web page. 3. 3. About your use of the library space ub lic at io n 18. Do you use SJSU library’s physical space? No Yes d fo rp 19. Please check which of the following activities you engage in while visiting the library. (Check all that apply) ce pt e Yes No ac Checking out library materials d Using photocopy machines an Using microfilm/microfiche machines d Visiting the coffee shop di te Using a library computer Using a study room ye Using library materials op Using non-English materials ,c Conducting research ew ed Writing a paper Placing an interlibrary loan / link+ request vi Using course reserves re Consulting with a librarian or library staff er Working with a group of classmates pe Working with a professor s Attending a class Th is m ss .i Working at a table in the library Sitting in the lounge seating (sofas or easy chairs) Browsing (new) books Spending time in contemplation or sustained thinking Reading or browsing periodicals Sleeping Meeting other people/friends Attending a special event Consuming food/drinks Other: (please specify) 253 Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen 20. Please indicate what possessions you bring to the library. (Check all that apply) Yes No Laptop computer 3. Cell phone 3. Briefcase or backpack l1 Personal copies of books or journals ta Library copies of books or journals or Snacks and/or drinks ,p Writing materials (paper, pen or pencil) ub rp ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo 21. Where do you sit in the library? (Check all that apply) Table with chairs Chair at a computer Chair at a microfiche or microfilm reader Study room Lounge chair or sofa Coffee shop Special Collections Cultural Heritage Center Children’s Room Other (please specify) lic at io n Other: (please specify) op 22. Do you have a favorite floor or location in the library? Which one? re vi ew ed ,c 23. Do you ever visit the library just to study, work, or relax, without using library resources (such as books, journals, or library computers)? Yes No Th is m ss .i s pe er 24. How did you find your way around the library? (Check all that apply) I learned on my own through trial and error I learned on my own by reading the maps and guides I asked a staff member A classmate or friend showed me around I took part in a guided library tour 25. When you are working on an assignment or a research project, do you conduct any of your research in the library? Yes No 254 Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University 3. l1 or ta 27. D o you use SJSU library’s electronic resources remotely? (This includes, for example, using online databases, e-journals, e-books, via the library Web site from home or a distant location) Yes No 3. 26. When you are writing a paper, do you write any part of it in the library? Yes No lic at io n ,p 28. T he King Library is a very particular building in that it serves both SJSU students and the San José general community. What is your experience or feeling, as a library patron and student, about this combination? d fo rp ub 29. In your opinion, are there differences between using the library remotely (using electronic resources via the Web site) and using the library’s physical space? (If so, what are the differences?) d ac ce pt e 30. I f you have any other observations about your use of library space that you would like to share, please use the space below. • Could you please provide a word or two that BEST describe this library: d an • What is the ONE best feature of this library? Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi op ew ed ,c • Other comments ye di te • What is the ONE worst feature of this library? 255 Valeria E. Molteni, Crystal Goldman, Enora Oulc’hen Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p or 3. ta l1 1. San Jose State University, “About SJSU: Facts & Figures,” (2012), http://www.sjsu.edu/about_ sjsu/facts_and_figures/ (accessed March 20, 2012). 2. California State University, “Analytic Studies,” (2011), http://www.calstate.edu/as/ (accessed April 27, 2012). 3. George M. Eberhart, “Three Plans for Shared-Use Libraries in the Works,” American Libraries 30, 1 (1999): 21–23; Andrew Albanese, “Joint San José Library Opens,” Library Journal 128, 14 (2003): 17; George M. Eberhart, “San José’s New Joint-Use Library Sets a Record,” American Libraries 34, 8 (2003): 16; Walt Crawford, “The Philosophy of Joint-Use Libraries,” American Libraries 34, 11 (2003): 83. 4. Christina A. Peterson and Patricia Senn Breivik, “Reaching for a Vision: The Creation of a New Library Collaborative,” Resource Sharing & Information Networks 15, 1 (2001): 117. 5. Paul Kauppila and Sharon Russell, “Economies of Scale in the Library World: The Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library in San José, California,” New Library World 104, 7/8 (2003): 255–266. 6. Patricia Senn Breivik, Luann Budd, and Richard F. Woods, “We’re Married! The Rewards and Challenges of Joint Libraries,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 31, 5 (2005): 401. 7. Christina A. Peterson, “Space Designed for Lifelong Learning,” in Library as Place: Rethinking Roles, Rethinking Space, CLIR Publication No. 129 (Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources, 2005), 56–65. 8. John N. Berry, “The San José Model,” Library Journal 129, 11 (2004): 34–37; George Plosker, “Revisiting Library Funding: What Really Works?” Online 29, 2 (2005): 48–53; Kirsten L. Marie, “One Plus One Equals Three Joint-Use Libraries in Urban Areas—The Ultimate Form of Library Cooperation,” Library Leadership and Management 21, 1 (2007): 27. 9. Richard F. Woods, “Sharing Technology for a Joint-Use Library,” Resource Sharing and Information Networks 17, 1/2 (2004): 205–220. 10. Danianne Mizzy, “Yours, Mine, and Ours: Reinventing Reference at San José,” College & Research Libraries News 66, 8 (2005): 598–599; Paul Kauppila, Sandra E. Belanger, and Lisa Rosenblum, “Merge Everything It Makes Sense to Merge: The History and Philosophy of the Merged Reference Collection at the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library in San José, California,” Collection Management 31, 3 (2006): 33–57; Harry Meserve, “Evolving Reference, Changing Culture: The Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library and Reference Challenges Ahead,” The Reference Librarian 93 (2006): 23–42. 11. Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 117. 12. Tony Hiss, The Experience of Place (New York: Vintage, 1991); Marc Augé, Non–Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (New York: Verso Books, 1995). 13. Wayne A. Wiegand, “Library as Place,” North Carolina Libraries 63, 3 (2005): 76–80. 14. Scott Bennett, “Libraries and Learning: A History of Paradigm Change,” portal: Libraries and the Academy 9, 2 (2009): 181–197; Frieda Weise, “Being There: The Library as Place,” Journal of the Medical Library Association 92, 1 (2004): 6. 15. Lisa M. Given, “Setting the Stage for Undergraduates’ Information Behaviours: Faculty and Librarians’ Perspectives on Academic Space:,” in The Library as Place: History, Community and Culture, ed. John E. Buschman and Gloria J. Leckie (Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007), 177–189; Logan Ludwig and Susan Starr, “Library as Place: Results of a Delphi Study,” Journal of the Medical Library Association 93, 3 (2005): 315; Jeffrey Pomerantz and Gary Marchionini, “The Digital Library as Place,” Journal of Documentation 63, 4 (2007): 505–533; Les Watson, “The Future of the Library as a Place of Learning: A Personal Perspective,” New Review of Academic Librarianship 16, 1 (2010): 45–56. 16. Henry D. Delcore et al., “The Library Study at Fresno State” (2009), http://www.csufresno. edu/anthropology/ipa/ (accessed April 17, 2011) 35. 3. Notes 256 Th is m ss .i s pe er re vi ew ed ,c op ye di te d an d ac ce pt e d fo rp ub lic at io n ,p 3. l1 or ta 17. Scott Bennett, Libraries Designed for Learning (Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources, 2003), 20. 18. Karen Antell and Debra Engel, “Conduciveness to Scholarship: The Essence of Academic Library as Place,” College & Research Libraries 67, 6 (2006): 536–560. 19. Ibid., 552. 20. David Kohl, “Where’s the Library?” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 32, 2 (2006): 118. 21. Pomerantz and Marchionini, “Digital Library as Place,” 528. 22. Valeria E. Molteni, “Providing Bilingual Library Services on a Multicultural Campus,” (presentation, CARL Conference, Going Global: Academic Libraries in the Age of Globalization, Irvine, California, April 2–5, 2008). 23. Shannon M. Staley, Nicole A. Branch, and Tom L. Hewitt, “Standardised Library Instruction Assessment: An Institution-Specific Approach,” Information Research 15, 3 (2010), http://informationr.net/ir/15-3/paper436.html (accessed March 31, 2012). 24. Antell and Engel, “Conduciveness to Scholarship,” 555–560. 25. Gloria J. Leckie and Jeffrey Hopkins, “The Public Place of Central Libraries: Findings from Toronto and Vancouver,” Library Quarterly (2002): 326–372. 26. Carmel McNaught and Paul Lam, “Using Wordle as a Supplementary Research Tool” Qualitative Report 15, 3 (2010): 630–643. 27. Amanda Clay Powers, Julie Shedd, and Clay Hill, “The Role of Virtual Reference in Library Web Site Design: A Qualitative Source for Usage Date,” Journal of Web Librarianship 5,2 (2011): 96–113. 28. San José State University, “Office of Institutional Research,” http://oir.sjsu.edu/ (accessed November 17, 2011). Since 2012, this URL has been forwarded to the Institutional Effectiveness & Analytics page at http://iea.sjsu.edu/. 29.Ibid. 30.Ibid. 31.Ibid. 32.Ibid. 33. Bennett, “Libraries Designed for Learning”; Delcore et al, “Library Study.” 34. Crystal Goldman and Valeria E. Molteni, “Innovative Library, Innovative Space: How SJSU Students Use It” (presentation, CARL Conference, Creativity and Sustainability: Fostering User-Centered Innovation in Difficult Times, San Diego, California, April 5–7, 2012), www.carl-acrl.org/conference2012/2012CARLproceedings/ InnovativeLibraryInnovativeSpaceHowSJSUStudentsUseIt.pdf (accessed September 29, 2012). 35. Valeria E. Molteni, “The Library as Space of Learning: Who is Using It?” (poster, 2nd National Joint Conference of Librarians of Color, Kansas City, Missouri, September 19–23, 2012). 36. Delcore et al., “Library Study”; Bennett, Libraries Designed for Learning; Ludwig and Starr, “Library as Place”; Pomerantz and Marchionini, “Digital Library as Place”; Watson, “Future of the Library.” 37. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, “Student Computing Services Center,” http://library.sjsu. edu/student-computing-services (accessed September 29, 2012). 38. Bennett, “Libraries and Learning”; Weise, “Being There.” 3. Experiences of the Student Population at an Urban University