No Mere Reflection: Mirrors as Windows on

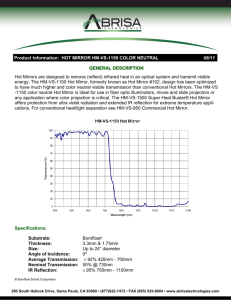

advertisement