Identifying Teacher Practices that Support Students

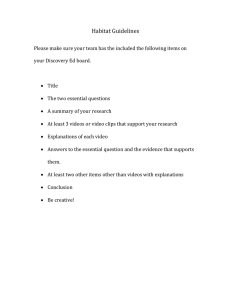

advertisement