Volume 7 • Number 13 • June 2015 ISSN 1729

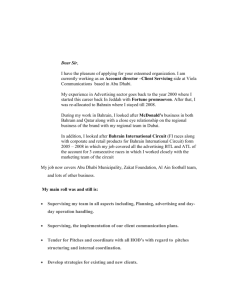

advertisement