Volume. 35, No. 4, October 2014

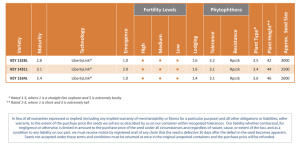

advertisement