The status of industrial vegetable oils from genetically

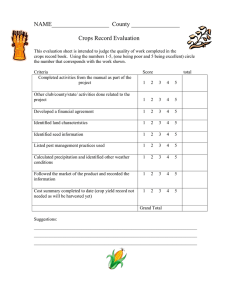

advertisement