No Guarantees - Bellwether Education Partners

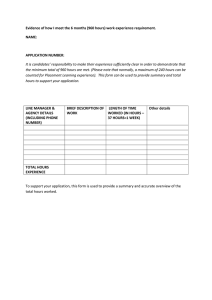

advertisement