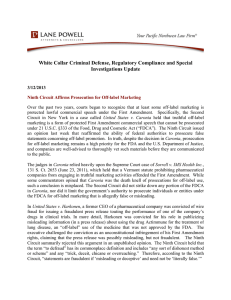

“False or Misleading” Off-Label Promotion?

advertisement