Relationship of Riparian Reserve Zone Width to Bird Density and

advertisement

TrevorA. Kinley and Nancy J. Newhouse,Sy van Consut ng Box 249, nvermere,

BritishColumbia,VOA1K0 Canada

Relationshipof RiparianReserveZoneWidthto Bird Densityand

Diversityin SoutheasternBritishColumbia

Abstract

Britjsh Columbia forestry guidelinesrequirc riparian managementareasof20 to 50 m wid$ betwccn small streamsand cutblocks.

composed of reserve zones (no timber hanest) and/or managementzones (limited timber harves0. Cuidelines in Kootenai

Nari,,rnalForest,Montana. limit fbrest huvesting for 30 m adjacent1(lpermanenlstfeams. As one slep in providing a basis lo

assesssuch guidclines. we compared(1) habitat strucrurebetwccn spruce-dominareddparian forest and pine-dominatedupland

f'rrest, (2) breeding bird characterisitics(density of detections.spccicsrichnesr, lpecies diversity and speciesequitability) be

tween riparian and upland tbrest. and (3) breedingbird characterisilicsbctween riparian resen'ezonesofvrrious widths (aveng

ing 70. 37. or 14 m wide). The study occurredin the Montane Spruccbiogeoclimalic zone of southeasternBritish Colunbia. ln

felation to upland forest. nparian forest had greatertall shrub and canopy covet but felver live trees. Snag densily, low shrub

cover.and coarsewoody debris did not difter at P<0.05. The two habitat typesdid not difTerin meanbird speciesrichncss per site.

bul riparian forest had greater speciesdiversity and spcciesequirabilit]'. greater density of all speciescombincd. atd greater

density of thrcc indivjdual species. The density of all birds combined. all riparian-associatedbirds combined. and t})Jccof the

four riperian associatcdspeciesincreasedwith increasingreserle zonc widlh. Speciesdiversity and speciesequilability did no1

differ significantly anong treatments.

Thc widths ofriparian managemenrareasrequircd under cunent British Colunbia and Kootenai National Forestgujdelines

nanower than the widest caregoryofreservesinlestigated in this study (70 nl). Our dala indicate that prescribed

are considerabl_v

dparian managementareasunder cunent guidclineswill have loner densitiesof total birds and ofripatlan associaledbirds than

ifreserres \\'ere reouired to arerase 70 m in width.

lntroduction

Riparianhabitatsareconsideredessentialfor many

wildlife speciesbecauseof high plant and anrmal productivity,complexhabitatstlrcturc. proximity to water, and role as movementcorridors

(Thomaset al. 1979b,MorganandWetmore1986,

Bunnell et al. l992, Bunnell and Dupuis 1993,

Naimanet al. 1993,Stevenset al. 1995). In the

Montane Spruce biogeoclimatic zone of British

Columbia, where this study occurred, approximately 65cloof vertebratespeciesare associated

with riparian areas(Bunnell and Dupuis 1993).

The Forest PracticesCode of British Columbia rcquiresthat forest managen maintain riparian managementareas(RMAs) betweencutblocks

and streams,consistingofriparian reservezones

(RRZs) with no forest harvestand dparian managementzones(RMZS)with limited harvest.The

width of thesezonesis variable.dependingon a

stream'schannelwidth and its valuefbr fisheries

or as a domestic water supply. For strcamsless

than 20 m wide. reservezonesvary from 0 to 30

m and managementzonesvary from 20 to 30 m,

for a toral of 20 to 50 m (BC Minisry ofForests

and BC Environment 1995). The national lbrest

nearestto the study areais Kootenai,in northem

Montana.Guidelineslbr KootenaiNationalForest

require that permanentstreamsbe buffered by

streamsidemanagementzones (SMZs) that are

generally 30 m wide and in which only limited

timberharvestingis permitted(KootenaiNational

Forest 199,1).

I n w e s r e mN o r t hA m e r i c r .I i t t l er i p u r i r nr e searchhasbeenspecificto conifer-dominatedriparian habitatsof dry to mesic inland montane

regions. However,it is well establishedthat the

creationof edgeand the ratio of edgeto interior

forest habitat have significant effects on faunal

characteristics(Thomaset al. 1979a,Strelkeand

Dickson 1980,Kroodsma1982,Hansson1983,

Kroodsma1984,Wilcove 1985,Thompsonet al.

.[992.Faaborget al. 1993).Recently,severalstudies have specifically addressedthe effectsof the

width of riparian reservezonesor management

zones on bird community characteristics. Narrow reservesgenerallytail to provide habitat for

the complete range of naturally-occurringbird

species(Staufferand Best 1980,Croonquistand

Brooks 1993, Spackman and Hughes 199,1,

Darr'eauet al. l995.Gyug 1995),but resultsdiffer

NorthwestScience,Vo]. 71, No. 2, 1997

o l99l br-Lh€Nonhscn s.icnrilicA$o.iarionAll ilhrs Fsened.

15

betweenlandscapes.In somesituations,

no major difl'erencesare apparenteven over a broad

rangeofriparian rcservezonewidths (Snith rnd

Schael'er1992). Furthermore.McGarigal and

VcContbI lQa2r rcp.n rrr'.rscu hereriparianurrnes

exhibitlower speciesdiversityand densitythan

upland sitcs. Theretbre, it is not clear to what

extentcurrentforestryguidelineswill maintain

lhc ecologicalvaluesof riparianhabitatsof Lhc

inlandNorthwcst.

As one stepin providing an empirical basisto

:ls.es:!:uidcline\.$ e comparedI l) hahitatstrucrure

betweenriparian and upland tbrest, (2) brceding

bird characterisiticsbetweenriparianand upland

forest, and (3) breeding bird characteristicsbet$'eeniparian reservezonesofvarious widths in

the MontaneSprucebiogeoclimaticzoneofsoutheastemBdtish Columbia.

Methods

This study occurred in the "Dry, Cool Montane

Spmce" (MSdk) biogeoclimatic subzoneof the

lnvermereForestDistrictin southeastem

British

Columbia(Figurel) at elevations

of I 100to 1300

m. Mean annual precipitation fbr the MSdk is

590nur. with a meansummertemperature

of about

8.5'C and a mean winter temperatureof about

3.0'C (Braunandland Curran 1992). Fifteen

study sitcs were establishedadjacentto streams

with channelsI to 10 m wide. parallelingone

sideofthe streamlbr 300m andextendingupslope

fbr 100m. Siteswcrea minimumof 500mapart

at the closcst points. The forestedarea in each

siteincludeddparianfbreston historicfloodplains

and upJandfbrest farther upslope,and was 80 to

1,10years oJd. Sites exhibited complex vegetational pattems,but basedon the MSdk classifi

cation (Braumandl and Curran I992), riparian

fbrest correspondedmost closely to the "hybdd

white spruce- dogwood ho$etail" (Pice.rglarca

s engelmanni- Contus stolonifera - Equisetum

an'eirse)series.anduplandfbrestwasmost sinilar

to thc 'lodgepolepine - Oregongrape pinegrass"

(Pinus t:ontorta- Mahonia uquifoliun Calanogrtstis rubescens)sedes.Control sitescontained

only riparian and uplandforest,while treatments

included recent clearcuts(<l to 5 years old) at

the upslopeend. The threeteatmentswereclassed

asnarrow,mediumor wide resen'ezones.according to the width of forest remaining betweenthe

cutblock and the stream(Table I and Figure 2).

These strips of forest correspondedto RRZs of

ForestPracticesCodenomenclature,andincluded

both riparian and upland vegetation. Forest on

the oppositesideofthe streamfrom eachsite was

in a mature, uncut state and was vegetationally

similar to the study site. Habitat typesin all sites

weremappedat l: 1000scale,basedon fansects

run perpendicularto the strcamat 25-m intervals.

The forestedareaofeachsitewasdeterminedusing

a digital planimeter,then divided by 300 m to

yield the mean width of each reservezone.

Coarse woody debris (CWD) volumes were

assessed

using the methodofLofroth ( 1992).and

included all pieces210 cm diameteron one 200m tnnsect per habitattype at 15 sites. Sampling

methodsfor vegetativecharacteristics

were modified from provincial standards(HabitatMonitoring Committee 1990) becausethe linear nature

of our ripaLriansitesand the habitat units within

TABLE 1. Chatacteristic! of 15 riparian \tLidy sites in the Moniane Spruce7onc. ln\ermefe ForesrDislrict. B.C., 19939 199,1

ao|ltrnl

Charr!tcri,tic

S . r m p l eS i z e

Width ol Riparian Forest (m)

\lean (Range)

Width of LrplandFore\l (n)

Mern (Rarge)

TdalWidth of RRZ (m)

Mean (Range)

Width of Curblock 0n)

Mcan (Range)

Tolal Sitc \lidth 0r)

Length Parallel to Strean 0n)

S l o p e( L = < 1 0 ' l . :H = > 1 0 %)

'76

lJ(r ren.

Wide

ReservcZone

Kinley and Newhouse

5

27 (9 :15)

73 (55-91)

t00

:r00

2N.2S.1W

lL.:lH

3

25(r r 4.1)

,15(29 54)

10 t61-73)

30 (27-36)

100

300

1N.2E

3H

Mcdium

Resene Zone

)

2 l (1 3 , 3 1 )

r 6 ( 1 02 3 )

37 (33-.13)

-67)

63 (5',7

N-arrow

ReserveZone

2

l,l ( l3- 1,1)

100

t)

l,l (13-l:1)

86 (86-87)

100

300

3N.2S

300

]N,IE

2L.3H

2L

't;a-

''

",j":1

-''r':'

. \ - .C r ee z

Lr l_--.'

*',,j,

Temn4|;{*n*

J

rll

5

etl

Dqyck4

o

l @

t('r

.':,'

qt C2

tta / J \\)

',,:;. ',"r';,

s.!i.

-;

,ti:,

(D

k

'.:

3

(\

.t

|

o

o

.1.

'nPek

FronceS-7

N

British

Columbia

l/\

1 0k m

o

Controls

@ WideReserves

@ MediumReserves

NarrowReserves

o

Figure L Srudl area and study sile bcations.

RipilriirnReser\eZone Birds

qy'

i : ; '

f

t

,

siteboundary

.

1100m'.

I

I

;

::

:,.r:.

: ,:.

,.

..

I

,

,

stream

i

E

:l

meanwidthof

reservezone

unharvested

forest

ControlSites

cutblock

.,,i

cutblock

.: ,. ., ,: ,; ",'

WideReserveZones

it-t-''*:===4

MediumReserveZones

cutblock

I-'---;g.'*

NarrowReserveZones

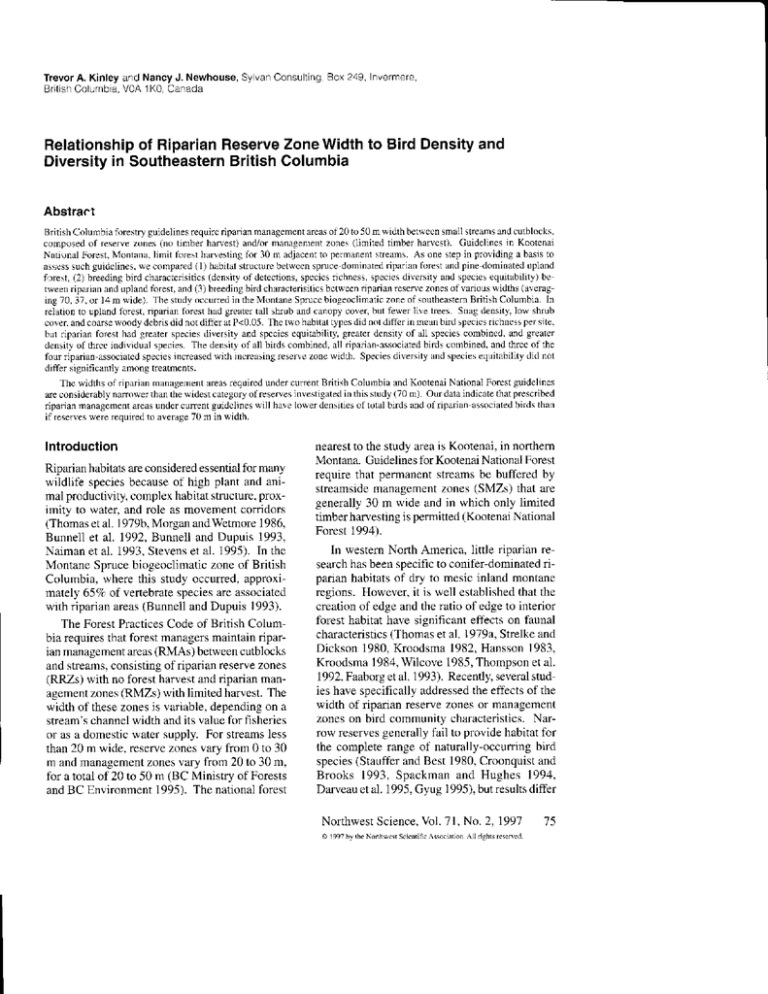

Figure 2 Control and rreatmenttypes.

78

Kinley andNewhouse

them precludedthe use of randomly-oriented

transects.and madeit necessaryto samplefrom

smallerplots (4 m mdius) than recommendedfor

forestedhabitats. For each habitat type at each

site,fbul circularplotsweredrawnon habitatmaps

using random X and Y coordinates,then trans

fered to the field. Within eachplot, the following data were recorded:number of snags,number of trees (>10 m tall), percent canopy cover

(using a spierical densiometer),percentcover of

the tall snrub stratum (2 to 10 m), and percent

cover of the low shrub stratum (<2 m). Twotailedt-testswereusedto detenninewhethervalues

diff:red among habitats. Becausethe study was

iD:endedto be exploratory rather than comprehensive,samplesizeswere low andP valueswere

not adjustedfbr multiple comparisons.

Each site was divided into a bird survey grid

of twelve 50 m x 50 m plots, anangedin an array

of six squaresaligned parallel to the streamby

tuo squaresdeep. The grid covered the entire

300 m x 100 m site. Thus, in all but contols ir

included both the cutblock and the rcscrvezone.

Plot boundarieswere marked on l:1000 habitat

maps. Each site was visited three times during

May andJune,oncein eachofearly, mid and late

moming. On each occasion,an obseryerspent

tive minutes at the centerof each plot, marking

locationson habitatmapsofall birds seenor heard

within the plot.

Speciesrichness(numberofbird species)was

tallied lbr eachsite,and alsofor eachhabitattype

in contlols. Bird density (number of detections/

ha) was calculatedfor each speciesand for all

speciescombined. In control sites,dersity was

calculatedseparatelylbr riparian forest and upl u n d l b r e s t . R i p a r i a n - r s w r c i a tsepde c i e sw e r e

definedby determiningwhich species'popula

tions were significantly more abundantin dpalian forestthan uplandforcst in control sites.This

wasaccomplishedusingone-tailedt-testsfor species which general referencesor other studies

indicatedwereriparian-associated

in similar ecosystems(Farand 1983a,1983b,1983c,Godfrey

1986,Cyug 1995,Scon 1987,Campbellet al.

l990a,1990b,Peterson1990,Semenchuk1992),

a n d u r i n g t u o - t a i l e dt - l e \ l \ l o r ( , l h e r{ p e c i e . .

Densitiesof eachriparian-associated

species.all

riparian-associated

speciescombined,and all

speciescombinedwere eachcompared(ANOVA)

among treatments(narrow. medium or wide reservezone). Contols were usedto define dpar-

ian-associatedspecies.as describedabove. but

were not compared to reserve-zonetreatments

becausebird useofstreamsideareasmay be qualitatively dift'erentin reservezonesthan in intact

forest, as a result of temporary "packing" into

reservezonesof birds that formerly occurredin

adjacentioggedland (Lehmkuhlet al. 199l, Gyug

l 9 q 5 ) . T h u . . t h ep r e s e n coef a b i r d i n r r e . e r r e

zonemay not reflect the samelevel of useor habitat

value that it would in a forest standwidely separated fiom cutting. A regressionequation was

calculated

for resenezonewidth (m) versusdensiq,

of ripadan-associated

birds. Riparian-associated

specieswere determinedbasedon two years of

data but other comparisonswere based on one

yea.r.asthe tull rungeoftreatmentswasonly studied

in one year. Speciesdiversity and speciesequitability were also comparedamong habitat types

fbr controls and amongtreatmentsusing the fbllowing equations(Krebs1989):

H = -I (p)(tog,op,)

j-t

where:

H = Shannon-Wienerindex of speciesdiversity

s = numberof speciesat site

pi = propoftion of samplebelongingto i'h species

| - Llllnn

a

where:

I = speciesequitability

S = number of speciesin all sites(as an approximation of the numberin the community)

Results

In comparisonto uplandforest,riparianforcsthad

greatercanopycover,a lower densityoflive trees,

and greatertall shrubcover (Table2). CWD volume, snag density and low shrub cover did not

difter significantlybetweenthe two habitattypes,

althoughthe calculatedP value for CWD (0.19)

suggeststhe possibility that CWD values were

greaterin dpadan forest.

Within controls.speciesrichnesswas similar

betweenriparian forest and upland forest: mean

richnessper site was 7.3 for both riparian and

upland, while total richnesstbr all five siteswas

22 for riparian and 19 for upland. Bird density

washigher in riparianforestthanin uplandforest

Riparian ReserveZone Birds

79

TABLE I

Ripafirn linest anduplandforcsl habitarathibutes

in 15 nalure st nds ofthe N{ontaneSpruccrolte.

I n v e r m e . eF o r c n D i s t r i c t ,B . C . . 1 9 9 3 - 1 9 9 . 1 .

Habilat Arribulcs

Ripdian Forest Upland Forest r Ten

mean

SE

lnean

CwD (n'Aa)

l0l

Canopycolcr (q )

Lile trees(\tems/ha)

11

ll

2

56

.10

79

61

82

116

t0

2t

666

Snagslctems,ha)

Tall shrubs(tZ.co\'ef)

169

Low,ihrubc(9: covcr)

23

l5

2

3

SE

13 0.19

3 <0.01

85 0.04

11 0.91

I

0.05

2

0.59

tbr all speciescombined( 12.2versus6.5 detections/ha,p=0.03)andfor threeindividual species:

golden-crownedkinglets (Regrllls sutrapd: 3.8

versus 2.3. p=0.04), Hammond's flycatcher

(Enpidonttx lnmmoirdill 1.7 versus0.5, p=0.03)

and w i nter w r et (Trog ktth t es t rog I ocl2-t e.;; 0.5

versus0.0, p=0.01). Speciesdiversityand species equitability were also higher in rhe riparian

(H^,"=0.96,H.".=0.86; Jo,u=0.62,Jr".=0.55).

Speciesdensitiesby habitattype arc summarized

in Table3.

Riparian-associated

birds were consideredk)

be the thrce having greaterdensitiesin the dparian than upland, plus the Townsend'swarbler

(.Dendrcicatownsendl)r. Densitiesof thesetbur

speciescombined differed bet*een treatments

(ANOVA, P<0.01;Table4). This was alsotrue

fbr each of the dparian-associatedspeciesindividually (P<0.01). exceptHammond'sfl ycatcher

(P=0.26). The regressionof reservezone width

versusdensity of riparian-associatedbirds (Fig

ure 3) had a correlationcoefficient (R2)of 0.803

and the regressionequation:

y = 0.093x- 0.303,where

y = densityofriparian-associated

birds (detectionsfta)

x = reservezone width (m)

ln addition,the densityof all speciescombineddifferedsignificantlyamongfteatments.

with

higherdensitiesin wider sites(Table4). How

ever,speciesdiversityand speciesequitabilityper

sitedid not dilfer significantlybetweentreatments

(P=0.15), with mean values of Hnoo=0.8,1.

Hn,uo=O.7

l, H*o=0.89 andJ\iR=0.54,JMED=0.46,

J*u,=0.58. Densitiesby treatmentfor each species are summarizedin Table 3.

80

Kinley and Newhouse

Discussion

The diflerencesbetweenriparian fbrest and upland forest for several of the habitat aftributes

indicate that these forest types provided different environments. For example.riparian fbrest

provided greatercanopy cover with fewer trees,

greatertall shrubcover and possiblyrnoreCWD

than uplandfbrest. Thesedifferencesemphasize

the impofianceof maintainingthe rip.rrianforest's

structural attributes to provide landscape-scale

hrhitutrariabiliry.particularllhecru.e.pccie.cln

be strongly associatedwith particular structural

patterns(Marzluff and Lyon 1983,Sharpe1996),

and riparian forest composesa relatively snrall

parl of the landscape.

We found bird density. speciesdiversity and

speciesequitability to be higher and speciesrichnessto be similar in riparian forest comparedto

adjacentupland forest. This was true despitethe

riparianfbrestpofiion ofcontrol sitesbeing considerablysmallerthan the upland ponion (recall

Table l). These results suggestthat, at least at

the stand level, riparian areashave a disproportionately high value in maintaining diverse avifaunasin conif'er-dominatedlbrcsts of the Mon

taneSpmcezone. Therefore.guidelinesintended

to maintainripadan forest arejustifiable trom an

avianperspective.Ow resultsareconsistentwith

the findings of many other authorswho reported

greaterabundanceor diversity of birds in riparian areascomparedto upland areas(Thomas et

al. 1979a.Staufferand Best 1980,Emmedch and

V o h s l 9 8 2 , K n o p f 1 9 8 5 ,B u n n e l le t a l . 1 9 9 1 ,

CroonquistandBrooks 1993.LeungandSimpson

1994). However, the results of several studies

indicated patternsopposite to this. Mccarigal

andMcComb (l992) foundthatuplandforestin

the wet coastal region of Oregon had more di

verse avifaunasand higher populationsthan adjacent riparianforest. The authorsofthe Oregon

study suggestedthat their study area.relative to

more arid regions,showedlesscontrastbetween

dpadan and upland habitats in terms ot water

availability,microclimate,andsttuctumlcomp]exity. In fact,overstorycover,low shrubcover,snag

density and conifer basalareawere all greaterin

upland than riparian areasin their study. Habitat

useby someindividualspeciesalsodifferedgreatly

betweenour study andthe Oregonstudy. We found

golden-crowned

knglets andHammond'sflycatchers to be more abundantin riparian forest. and

TABLE 3. Mean densit) (detections,4ra)

ofbird\ iD 3-ha sites.rdiaceniio streamsin ihe luontane Sprucezone,InvermereFbrest

Distric!. B.C. Comparisonsof lbrcsr rlpc arc poolcd lbr 1993 and 199,1.and lhose of reservezone width are from

199'1.

Specics

ForeslTypc

Riparian

Upland

(n=51

(n=5)

r!ra!

tTutdt6 tnisraturius)

Black cappid Chickadee

\Pdtu\ dtticttpi11usJ

Bro\tn Creeper

(C. rthiu dt|eri(and)

Bro',r'n hcadcdCowbird

lM0lothru\eter)

Calliopc Hunmjngbird

(Stellula cullioF)

Cedar \\'axwing

in)

lBonb\itia &tn

Chippillg Sparrow

lSt)i.elh putserinu)

D a r k - e l e dJ u n c o

\Junco hrenlalit)

Golden-crownedKinglet

(ReRulLts

sdtrapa)

Gray Jay

lPerisorcus candde sis)

Grert Cr:lv O$l

Hairy-Woodpcckcr

(PiL0ifus rillosu!)

H a m m o n ds F l ) ' . c a r c h e r

I L nt id o ntLthdnnntftr i i)

NfacGillivray s \4'arbler

(Oporcnt\ tolniei)

Mountain Chickadee

(t'utut ga,theli)

Oli!e-sided Flycatcher

\Co topus borcalis)

Pileated\\bodpecker

lDtlcopus pileatus)

5L

!!q!

! Tes!

5L

0.09 0.06

0.02 0.02

0.35

0.03 0.03

0.05 0.05

0.80

0.00 0.00

0.02 0.02

0.3-l

0.03 0.03

0.02 0.02

0.i17

0 .t 4

0 . 1I

3.76 0.66

0.'19 0.11

0.06

2 . 3 1 0 . 3 5 +0.0,1

0 . l 5 0 . 1 5 0.00 0.00

0.33

0.06 0.06

0.33

0.00 0.00

1.73 0.56

0.11 0.11

*0.03

0.06 0.06

0.00 0.00

0.33

0.00 0.00

0.02 0.02

0.33

0.04 0.0.1 0.00 0.00

Widc

(n=3)

ReserveZone Tlpe

Nlcdium

Narrow

(n=5)

(n=2)

ANOVA

I!]c!! 5L

0.0'1 0.04

I]]ca! SL loeaa SL

0.03 0.03 0.00 0.00

-L

0.7E

0.05 0.0s

u.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.35

0.0,1 0.04

0.00 0.00 0.06 0.06

0.35

0.00 0.00

0.00 0.00 0.06 0.06

0.13

0.09 0.09

0.09 0.09 0.06 0.06

0.96

0.84 0.25

0.71 0..r5 0.r8 0.r8

0.80

2.9',70.22

t.44 0.22 0.62 0.39

0.01

0.r8 0.04

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.01

0.04 0.0.1 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.3s

).02 0.11

1 . 1 90 . 3 0 0 . 6 2 0 . 5 t

0.26

0.00 0.00

0.00 0.00 0.06 0.06

0.r3

0.09 0.09

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.35

0.0,1 0.011 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.35

0.54 0.20 0.76 0.38

0.67

0.0,1 0.0,1 0.00 0.0 0.00 0.00

0.35

0.33

(Pinicold enucleatoa

Pine Siskin

(Carduelis pinus)

Purple Finch

(Carp)daus purputeu')

Red Crolsbill

(Ln\ir.t cutrirosrra)

Red breastedNuthatch

(Sitta tanadensit)

Red-napedSapsucker

(Sfi ,"rdp i c us nut hat i s)

Ruby-cfowned Kinglet

lRegul s calendula)

0.59 0.38

0.68 0.27

0.8,1

1.08 0.76

0.91 0.9r

0.62 0.50

0.78

2 . 3 0 2 . 1 1 0.09 0.09 0.06 0.06

0.3,r

0.03 0.03

0.09 0.06

0.19

0.tr4 0.0:l

0.03 0.03 0.13 0.13

0.50

0.54 0.5'+ 0.00 0.00

0.33

0.00 0.00

0 . 0 00 . 0 0 0 . r 7 0 . 1 7

0.r3

0.03 0.03

0.58

0.0'1 0.104 0.31 0.28 0106 0.06

0.70

0.06 0.05

conllnucd. ncxl page

Riparian ReserveZone Birds

8l

TABLE 3. condnued

Species

Forcsl Type

Ripaian

Upland

(n=51

!rE!!r

R u f o u sH u l n m i n g b i r d

0.00

6cLasphorus n[L )

Solitar! Virco

0.00

\Virco \olituriIs)

SpruceGrouse

0.1I

\De, rasapus candulen'i5J

Swrinson s Thrush

0.30

(Cutharus ustuLan6)

Townsends Warbler

1.26

(Denlnxn touse/..lii)

Varied Thrush

0.20

llxortusId.t,ius)

\\'arbling Virco

\\Ireo giltus)

SL

Eelrn -SL

0.0

0.02 0.02

0.00

| Test

Wide

(n=3)

RcserveZone Type

Mediun

Narrow

(n=5)

(n=2)

ANovA

!]c4! lL

lscdn,sl

0.33

0.09 0.05

0.03 0.03 0.00 0.00

0.25

0.l5 0.09

0.l2

0.:14 0.37

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.24

0.07

0.00 0.00

0.r5

0.11

0.36 0.16

0.16

0.98 0.55

0.20 0.08 0.11 0.ll

0.14)

0.17

0.67 0.33

*0.16

l.r-J 0.27

0.17 0.12 0.06 0.06

0.01

0.r2

0.05 0.05

*0.13

0.09 0.05

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.05

o.23 0.22

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.07

0.25 0.25

0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

0.35

ae!!

_g

L

0.00 0.00

0.08 0.08

0.33

0.l7 0.12

0.00 0.00

0.1/

0.,19 0.17

0.00 0.00

*0.01

0.,130.15

0.00 0.00 0.06 0.06

0.01

0.25 0.13

0.30 0.11

0.19

0.21 0.lr

0.:180.35 0.2:1 0.01

0./9

(P rntaga I ullari( iTta)

White winged Crossbill

(l.orid le copten)

(Tn g I otl) t eI trc s lot^ t es)

Ycllo$ rumped \Varbler

(Dendrcica connata)

" P v a l u e s a r e b a s e do n o n c l a i l e d t - t e s t \ f o r

s p c c i e sw h i c h o t h e r L i l c r u t u r ei n d i c a t e dw c r e r i p a r i a n - a s s o c i a t eidn s i m i l a r

e c o s y s l e m sa. n d o n t w o t a i l c d I l e s t s f o r o l h e r s p e c i e s( s e e m e t h o d s ) . S p e c i e sf o r v h i c h o n e - r a i l e dt e s t sw e r e d o n e a r e

i n d i c a t e dw i r h a n * .

TABLE '1. Mean dcnsily (detections,fta*)of all bird speciescombined and of riparian associatedbirds in ten 3-ha sires that

iDcludedripanan reservezone\ in the Montane Sprucezone.lnvermere Forest Disfict, B.C., 199:1.

Wide Res. Zone

Species

All riparian-associatedspp.

Golden-cfowDed Kinglel

Hammond s Flycatcher

Townsend s Warbler

mean

SE

13.7

0.9

0.',7

0.2

6.5

3.0

2.0

Ll

0.,1

0.7

0.3

0.1

Medium Re!. Zonc

Narro{'Res. Zone

ANOVA

SE

5.3

2.8

1.4

t.2

0.2

0.0

0.1

0.3

0.2

0.3

0.1

0.0

,t.3

1.,1

0.6

0.6

0.1

0.1

0.1

04

0.5

0.1

0.1

<0.01

<0.01

<0.01

0.26

<0.01

0.01

* basedon rotal area in each site. which included riparian and upland forest plus

cutblock

winter wrens to occur only in riparian fbrest,

whereasin coastalOregon,Hammond's flycatchers

occuned only in upland sites, golden-crowned

kinglets were more abundantin uplandsites,and

winter wrens were less abundantbut presentin

upland sites. InVetrnonl. Spackmanand Hughes

(1994) found the greatestbird abundanceon

82

Kinley and Newhouse

transectsthat were the greatestdistanceftom the

high water mark of streams(>150 m). Murray

and Stauffer (1995) found in Virginia that some

specreswere positivelyand somewere negatively

associatedwith the riparian, with no significant

o v e r a l l r e n d si n r e l a t i \ ea b u n d a n coer s p e c i e .

nchness. The resultsof theselatter threestudies

p

@

r

6 6

(t

o

E 4

_c

o

E

2

o

o

0

0

2

0

4

0

6

0

8

0

Reservezone Width (m)

Figure 3. Density ofriparian associatedbirds ir 10100 m wide silesthat included riparianreserve

zoner in the Montane Sprucezone. lnve lcre ForestDistrict. B.C., 199'1.

indicatethatthe valueof riparianhabitatto agiven

species,guild or community may dift'er widely

betweenregions. Simi)arly, Knopf (1985) tbund

that the relative significanceofriparian nreasvaried

along an elevationalgradient. Our researchand

much ofthe literaturegenerallysuppofithetheory

that riparian areasare disproporionatelyimportant in maintaining diverse,abundantavilaunas,

but their value cannot be generalizedbetween

regions or elevations. Managementmust theretbre be basedupon a local understandingof the

distinctivenessof dparian habitat relatlve to upland habitat.

birds

We found densitiesof riparian-associated

and ofall bird speciescombinedto increasewlth

width for riparianreservezonesaveraging1,1,37

and 70 m. It is not kno$n how f'ar this trend

would continue fbr even wider reserve zones.

Controlswere not comparcdto this trendbecause

they had no definable width (therewas no adjacent cutblock) and becausehabitat use by birds

was probably qualitatively different in the contiguous forest of the controls, comparcd to the

stdps of fbrest and edge that made up the treatments. The observedpattem of increasingbird

density with increasingrese e zone width occurred despiteour cgnsusareasbeing the same

width (100 m) for all reservezone widths, the

true riparian vegetationbeing intact in all sites.

andtheoppositebankprovidinga continuousblock

of intact tbrest. Given these facts, our results

suggestthat for nanower reserves1) bird popu

lations did not fully compensatefor lost habitat

"packing" into a smallerfbrestedarea,as ocby

curs in somefragmentedtbrests(Lehmkuhl et al.

1991),or by making useofthe adjacentcutblock,

2) riparian habitat value may be allected when

adjacentupland forest is cut, even if the riparian

i t s c l Ii s n o tc u t .r n d J ) n a r o u e r r i p r r i a nr e . e r r e

zonesare of lessvalue than wider reservezones,

even if fbrest on the oppositeside of the stream

is intact. The 1ow habitat value of narrow and

medium reservezones rclative to wide reserye

zonesis consistentwith most otherstudies.Three

of the four speciesthat we consideredto be ripadan associatesand were sensitlveto reserve

zonewidth (Townsend'swarbler,winter wren and

golden crowned kinglet) were also found to be

sensitiveto fbrestedriparian corridor width by

Gyug (1995) in habitatsvery similar to those we

studied.Gyug found far fewer individualsof these

speciesin reservezoneslessthan 50 m compared

to those greaterthan 100 m, basedon siteshaving reservezonesand cutblockson both sidesof

thesfeam. InQuebec,Darveauet al. (1995)found

that dpadan reservestrips 60 m wide supported

forest dwelling birds in a pattern similar to controls. but that strips 20 or 40 m wide did not. In

Iowa, Stauffer and Best (1980) found a positive

correlationbetweenreservewidth and bird speciesrichnessfor sitesrangingfrom l0 to 250 m

Riparian ReserveZone Birds

83

wide. Croonquistand Brooks(1993)notedthat

sensitive specieswere absgnt from riparian resen es<25 m wide, andthatreserves>125 mwidc

were neededto suppofia nearnaturalavifaunain

Pennsylvania.

SpacknanandHughes(1994)found

thatripariancorridorsofabout 175m were needed

to maintain95'l. of the bird speciesfound in control sitesinVemont. In contrast.

SmithandSchaeler

(1992)tbund very little differencein bird commu

nity chancteristicsbetweenriparianreserves20 to

60 m wide and those75 to 150 m wide on urban

steams in Flodda, but felt this may havercflected

an inadequaterangeof widths studied.

Differencesin habitat characteristicsand bird

communitiesbetweenriparianand uplandforests

\ u p p o r lI h e p r a c t r c o

e I I n i ] l n t r i n i n rge \ e r v e :i n

streamsideforest. There are undoubtedlysome

speciesthat are less abundantor less active in

spruce dominated riparian forest than in lodgepole pine-dominated upland forest. However,

given the rarity of riparian fbrest relative to upland forest, differencesin habitat attributesbetween riparian and upland, and the high species

d i r e r s i r ;r n d r b u n d r n c ei n r h er i p a r i i l ni r. i s p r u d e n t o p r e f e r e n t i a lpl ;r r r ri d ep r o r e c r i rm

e anuge

ment to riparian habitatsin the Montane Spruce

z o n e . W h e r ep f f t i a l c u t r i n go c c u r si n r i p a r i a n

forest,thedifferencesin forestattdbutesthatmake

nparianhabitaruniquefrom uplandhabitatshould

be maintained. Riparian wildlife might benetit

ifprescribed volumesoftimber were removedin

patchesrather than unifbrmly. to ensurethat at

least part of the riparian habitat maintains its

uniquenessand high habiratsuitabiliry. This hypothesisrequiresinvestigation,

as it might also

result in greater habitat fragmentationper volume of timberremoved.

Dependingon channelwidth, British Colum

bia guidelinesrequireRMAs of 20 to 50 m on

small streams,with only a portion of this being

an RRZ and thereby being free from forest har

yesting(BC Ministry of Foresrsand BC Environment1995).Basedon thoseguidelines,RMAs

in the Montane Sprucezone may have considerably lower bird densities,includingthoseof dparian associates.than they would if they wer.e

70 m wide. A similarsituationis likely ro occur

in Kootenai National Forest, where timber harvestingis restrictedonly in SMZs 30 m wide

(Kootenai National Forest 1994). Fudhermore,

even the widest reservezonesstudied,if isolated

from contiguousmature forest, would probably

be severalordersofmagnitude too small to main8,1

Kinley and Newhouse

tain all speciesof neotropicalmigrants because

of the small anount of habitatarrdexpectedhigh

rates of nest predation and brood parasitism

(Faaborget al. 1993).Thus,ifone goalof riparlan managementtSto Supportneir,rnaturaldenSi

ties of riparian-associated

birds a nd maintain diverseavitaunasat the standlevel, ,it appearsthat

RMAs or SMZs shouldbe wider th an currently

required under British Columbia o,. Kootenai

NationalForestguidelines.and shouldr rot be isolated from larger standsof maturefbresL..

Currentriparianmanagement

guidelines.in B.C.

are not basedon vegetationalcharacteristics. A

"riparian"

managementarea will consist al_most

entircly of upland fbrest when the blnd of ril rar

ian vegetation is narrow, or altgrnatively, $

maintainonly a poftion of the riparianforestwhe

that vegetationtype extendsa greatdistancefron

the stream.This is likely becauseguidelineswerr

developedto maintainrecreational,aesthetic,tisheries and hydrological values, nor just wildlife

values. However.wildlife valuesand many other

values could more adequatelybe maintained if

prescribedwidths of reservezones.management

z o n e sl n d R M A s a : a u h o l ew e r e\ e e na 5m i n i mums,with provisionsto enlargethemwhereriparianhabitatextendedgreaterdistancesfrom the

stream,regardless

of chamelwidth,fisheriesva1ue,

or use of a streamas a domesticwater supply.

Acknowledgements

This project was completedunder conrracrro

British ColumbiaEnvironment,with funding provided by the Silvicultural SystemsFund. Rob

Neil andTrudy ChatwinofBC Environmentacted

ascontractmonito$. Marion Pofier and Clayton

Apps provided excellent field assistance.Jesse

D'E1ia,lrs Gyug.Eric Lofroth, KenMorgan,John

Richardson and Gerry Wright provided usef'ul

c' 'mmenl\on progre!\repon\or earlier\ er\itln\

of this manuscript.

Notes

1. The 1 lest for whether rhe Townsend,swarbier occurs at

greaterdensity in rhe dparian ihan the upland yietded a

P v a l u eo f 0 . 1 6 , u h i c h i s g e n e r a l l yb e y o n da c c e p r a b l e

significance. However. a morc ertensivc study in !ery

similarhabitat (Cyug 1995)found rhis speciesro be )re

c o m m o nl n l h e r i p a . i a n( P = 0 . 0 1 ) .s o i r i s i n c l u d e dw i | h

o l h e fr i D c t i J n

t r . . o c t . r r i(r, . r n r . ) . e ." t , h < . rf e . n o n . ( t , ,

LiteratureCited

BC Nlinisrr,vof I'oresis. rnd BC En!ircnmenl. 1995.Fofest

Pracricc\ Code of Briii\h Columbiu: Riparian man

agement area guidebool. Pro!. B.C.. Vicrofi . Bril

i s h C o l u m b i a . 6 8p .

Brauinandl. T. F., .rnd V. P Clunan. 1992.A field guide tbr

site idenrilicatio. and intefpretation lbr $e Nclson

l o r c s rr e g i o n .B C M i n . F o r .L a n d N l g n i . H d b k . N o .

1 0 . V i c t o r i r ,B r i t i s hC o l u n h r a .3 l 1 p .

Bunllcll. F. I-.. and L. A. Dupuis. 1993. Riparian habitais in

British Colulnbiai llrcir natureand fole.1, K. H. Nror

gan, and Nf. A. Lashn.rr (cds.JRipirian habital nlanagenenl lnd rcrearch. Prcceedings01 a $orlshop

sponsoredbr Envifonmcnt Canada arrd the British

Columbia Forestrr-ClonlinuingSludiesNen'ork. hekl

rn Kaiioops. B.C..:1-5N{a!: I 993.En\iron. Can.(Cdn.

w i l d l . S e r \ . ) ,D e l t a ,B r i t i s hC o l u n r b i aP

. p .7 - 2 1 .

Bunnell. P. S. Rautio. C. Fletchef..rnd,A..\'an $'oudcnbcrg.

l99l. Problen analysislbr jntegraredresourcenlan

r g c n c n t o f r i p a r i r n e c o s l s t e n s .B C M i n . F o r . a n d

B C N { i n .E n v i r o n . V

. i c l o r i a .B r i t i s hC o l u m b i a .1 3 0p .

Campbell, R. w.. \. K. Da$,e. L McTdggarl Clowan.J. M.

Cooper. C. w. Kaiser. and NL C E. NlcNall. 1990a.

NonT h c B i r d s o f B r i t i \ h C o l u m b i a .V o l u e I

pas\cnnesr Int(xluction. Loons through \!'atedowl.

R , ) J l B ' i r ' n C J I I n l - r i I l u . c r n r .\ c r o f i . .

. 1990b.Thc Bird\ of Briti,ih Colunbia. Volumc 2

Nonpasserines:Diufnal Birds ol Prc) through Woodpeckers.Ro),al Bfitish Colurnbia Museuln. Victoria.

Croonquist.Nf. J.,.rnd R. P Brooks. l9gl. Effects ofhabiut

disturb.rnceon bidco munitie\ in dpa]ian coridors.

J . S o i l a n d\ \ ' t t l c rC o n s ., 1 8 ( l ) : 6 5 - 7 0 .

Darl e.ru.\1.. P Bcauchesne.L. Behnger J. Huol. andP l-arue.

1995.Riparianfofest\trips ashabillt lorbreedingbirds

jn borexl l-orest.J. wildl. Ivlanage.59(l ):67-68.

E ' n m e r i c h J, . N L . a n d P A . \ b h s . 1 9 8 2 .C o l n p . r r a l i vuc s c o f

t b L t rw o o d l a n dh a b i t a t sb y b i d s . J . w i l d l . ! l a n a g e .

, 1 6 ( l ) r , 1 ,31 9 .

F | r b o r g .J . . N 4 .B f l t t i n g h r m .T . D o r o ! a n . a n dJ . t s 1 a k e1. 9 9 3 .

Habiiat frrgment.rtion in (hc lcmperate Tone:A per

s p e c t i v el i ) r m a n a g e r s1. , r D . N { . F i n c h , a n d P W

o tf n e o l r o p i c a l

S t a n g e(l e d s . )S | a r u sa . d m a n a g e n r e n

nigraloD birds. USDA For Ser!. Gcn. Tech. Reti.

R N i 1 2 9 . R o c k ) N I t r . f o r . R a n g e E x p . S t . r . .F o r t

C o l l i n s .C o l o r a d o P

. p.331 318.

Faffand.J. Jr (ed.). 1983a.TheAudubon Sociel) N{rstcrCurde

to Birdirg. \blumc li l-oons lo Sandpipers.Randoin

House oI Canada.t-td.. Tofonto.

l98lb. The Audubon Societ) trlascrGuide to Birding

-.

Volunre2: Gull\ to Dippers.Rrndonr HouseofC.Lnadr,

LId.. Toronto.

. 1 9 8 3 cT. h c A u d u b o nS o c i e t ym a s t e rg u i d cl o b r r d i n g .

lblume 3: Old \\brld ]lrblers to Spaffows. Randolll

House of Can d . Ltd . Toronto.

C o d i i c y . \ \ . E . 1 9 8 6 T h e B i r d s o f C a n a d a( t e v i s e de d . ) .\ u

rional \,luseums ol Cxnada.Ottall'a.

c ) u g . L . W l 9 9 5 . l i m b e r h a r l e s t i n ge l l e c l so n r i p d r i a na r

easintheNlonianeSprucezonc ol thcOkanaganHlghLmds.B.C.:,A.nnualprogressreport 1994/95.Pa|t Il:

. C Min. En!iron..

l n r c r j m b r e e d i n gb i r d r e s u L t sB

Penlicton,British Columbia. 2,1p.

Hrbitat Nlonitorirg Conmittce. 1990.Proceduresfof environmentd moniroring in range and wildlife habit.rt:

V e r s i o n , l . l . B C M i n . B n v i r o n .a n d B C M i n . F o r .

Vicroria. Bitish Columbia.

Hausson.L. 1983.Bird numbers acrossedgesbetlreen ma

ture conifer forest and clearcuB in ccntral Sweden.

O r D i sS c a n d .l , l ( 2 ) : 9 7 1 0 3 .

Knopt. F. L. 1985.Significanceof dprdm vegetalionto brccd

ing birds acrossan ahitudinal cliDe.1, R. R. Johnson.

C. D. Ziebell. D. R. P.rt|Lrn,P F. Ftbl]iotl. and R. H.

Hamre ftech. coofds.) Riparian ccosystemsand the]r

management:

Reconcilingconflicling uses.Fjrst Nonh

Gen.

AmericanRiparianConiirence. USDA For. Ser"r'.

Tech.Rpt. RM 120.Rock) Mtn. For.R nge Erp. S|a..

F o r t C o l l i n s ,C o l o r a d oP

. p. 105 111.

Koorenai National Forcsr. 199,1.Riparian arel guidelines.

Kootenai Nalional Forestplan. appendix 26. LrSDA

For. Ser!.. Ljbby. Montana.

Itcbs. C. J. 19E9.Ecological Methodology.Chapter I 0: Species di!crsily

easures.Harper Collins Publishcrs.

Nelv York.

Kroodsma.R. L- 1982.Edsc clicc! on breedingforest birds

c o n i d o r J . , A p p l .E c o l . l 9 : 3 6 1 a l o n ga p o $ , e r - l i n e

ll0.

1984. Effect of edge on breedinglbresr bird spccies.

_.

W i l s o nB u l l . 9 6 ( 3 ) : 4 1 64 3 6 .

l - c h l n k u h l J. . F . .L . F . R u g g i e r oa. n dP A . H a l l . 1 9 9 1 .L a n d scapc scalepatternsofforest fragmenlalionand $ild

lile richnessand abundancein the southernni$hirg

ton CascadeRangc. ,r l-. F-.Ruggiero. K. B. Aubry,

A. B. Carey,and M. H. Huff (tech. coords.)Wildlife

and legetatron of unnanagcd Douglas fir forests.

USDA For Sefv. Gen. Tech. Rcpr. PNw GTR 285.

P a c .\ w . R c s .S t a . .P o r t l a n do. f e g o n .P p . , 1 2 5 . 1 4 5 .

. ica wildlir! CompenL c u n g . N l . . a n d K . S i m p s o n .1 9 9 , 1M

s a t i o nP r o g n m C o l u m b i av a l l e y b i f d s u r v e y :S u m

ncr/iall l99l. BC Hydfo. Vancouver.British Colum

bia. and BC Min. En\,iron.. Landsand Parks,Nelson,

B r i i i s hC o l u m b i . r5. 2 p .

Lofroth. E. 1992.Measuremenrofhabitrl elenentsal the stand

l e \ e l . 1 , L . R . R a m s a y( c d . ) M e t h o d o l o g yl b r m o n i toring wildlifc diversiry in B.C. fi)rests:Proceedings

ofa rorkshop. Februdy 17. 1992.Crccn Timbers For

A s s n . , S u r r e y ,B . C . B C N l i n . E n v i r o n . .L a n d s a n d

Parks..Victoria, British Colunbia. Pp. 15 29.

N4arzluff.J. N{., and L. J. Lton. 1983.Snagsas indicatofs of

for opennestirg birds.1, J. \l: Da\is.

habilarsurtabilit,v

G. A. Good$in. andR. A. Ockenfels(eds.)Snagh.tbit.tt

nranagement:Proceedingsoi thc symposiumJune 79, 1983.NoflhemAnzona U'rilersiry.FlagstaftlUSDA

For Scrv. Gen. Tech. Rpl. RM-99. Rock) Mln. For

Range.Exp. Sta..Fon Colljns. Colorado.Pf. I .10-I ,16.

RiparianResen'eZone Birds

85

Mccarigal. K.. and W C. Mccomb. 1992. Streamsidever

sus upslopebreedingbird comnunities in thc cenrral

O r e g o nC o a s tR a n g c J. . W i l d l . \ 4 a n a g c 5. 6 ( 1 ) : 1 0 - 2 3 .

Morgan, K. H.. and S. P Wetmore. 1986.A siud) of riparian

bird cLrnmunitiesfron lhe dry interior ol Birish Col u m b i a .E n v i r o n .C a n . T e c h .R p r . S e r .N o . I L C d n .

Wildl. Ser\'.Pac. andYukon Reg.. Dcl|a. British Co

lumbia. 28 p.

l\run t), N. L., and D. F Stauffer 1995.Nongameuseot habital

in cenrralAppalachianriparianforcsls.J. Wildl. Man

age.59(1):78-88.

N a i m a n .R . J . . H . D e c a m p s M

. . P o l l o c k . 1 9 9 3 .T h e r o l e o t

dparianconidors in mainlainingregionalbiodi!ersity.

E c 0 l .A p p l i c . 3 ( 2 ) : 2 0 9 - 2

12.

Percrson,R. T. 1990. PetersonField Guides: \lesrcm Birds

(rhird ed.). Houghton MitTlin Co.. Boston.

Scort, S. L. (ed.). 1987. Field cuide ro rhc Birds of Norrh

America (seconded.). Nadonal GeographicSociety.

W'ashington.

Semenchuk.G. P (ed.). 1992.The Atlas of Breeding Birds

of Alberta. Federarion of Alberra Naruralists.

tsdmonton.

Sharpe.F I 996. the biolLrgicall,vsignificantaftributesof forest

c a n o p i e s| o s m a l l b i r d s .N o n h w S c i . 7 0 : 8 6 - 9 3 .

Snith. R. J.. and J. N{. Schaefer 1992.Avian characrerisrics

of an urban ripaian strip conidor. Wilson 8u11.

104(4):732-738.

Spackman,S. C.. andJ. W Hughes.1995.Assessmenr

of minimum stream comdc'r width for biological consen'a

ti()n: Speciesrichnes\ and dislribution along mid or,

dcr streams in VcrmoDt. LrSA. Biol. Conserr.

7 l : 3 2 53 1 2 .

Received27 Jme 1996

AcceptedJbr publicqtion l0 March I997

86

Kinley and Newhouse

Staulier. D. F.. and L. B. Best. 19E0.Habirar selecdon by

birds of riparian communiries: Evaluating effects of

h a b i i a !a l t e r a t i o n sJ.. W i l d l . M a n a g e ,. 1 , 1 ( 1 ) 1 , 1 5 .

Sle\'cns.V, F. Backhouse,and A. Eriksson. 1995. Riperian

managementin Brirish Columbia: An imponant srcp

to$'ardsmairtaining biodiversiry.BC Min. For. and

BC Min. Environ. I-ands and Parks Paper 13/1995.

Vicioria. British Columbia 30 p.

Slrelke.$'. K., andJ. c. Dickson. l980. Effecr of fbrestc tear

cutedgeon breediDgbirdsin castTexas.L Wildl. Manage.:Ll(3):559

567.

Thomar, J. \\'., C Maser, aid J. E Rodiek. 1979a.Riparian

zones. ,r J. W Thomas (tech. ed.) Wildlife hubitats

in managedforcsls: The Blue \{ounrains of Orcgon

andWashinglon

U.S D A F o r S e r v . A g H

. d b k .N o . 5 5 3 .

Pac. NW- Res. Sta..Pofiland. Orcgon. Pp.,10 47.

. l9l9b. Edges. /, J. W Thomar (cch. ed.) Wildlile

habilals in managedforesis: The Bluc Mountains of

OregonandWashingion.USDA For Ser!. Ag. Hdbk.

N o . 5 5 3 . P a c .N W R e s . S r a . .P o f t l a n d O

, r e g o n .p p .

48 59.

Thompron, F. R III. W- D. Dijak, T. c. Kulowiec. and D. A.

Hamillon. 1992. Breedjng bird populations in Mii

souri Ozark ibresrs with and withour clearcutring.J.

Wildl. Manage5

. 6(l):23 30.

Wilcove, D. S. 1985.Nest predarion in lbrest rracrr and $e

declineof migratorylongbirds.Ecol.66(,1):121

l-l2 t,l.