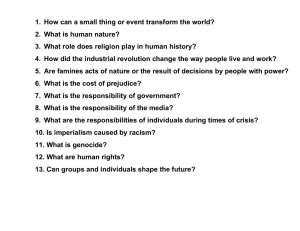

March-April Lincoln Douglas Topic

advertisement