EU Kids Online: Final Report

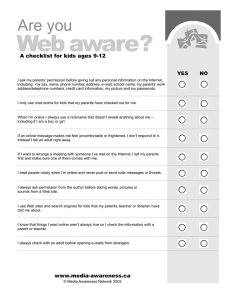

advertisement