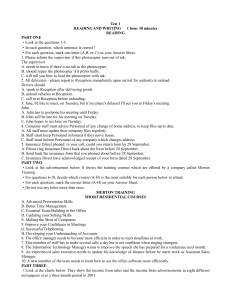

Report into a complaint by Professor Michael Thorpe at Mount

advertisement