China`s Energy and Emissions: A Turning Point?

advertisement

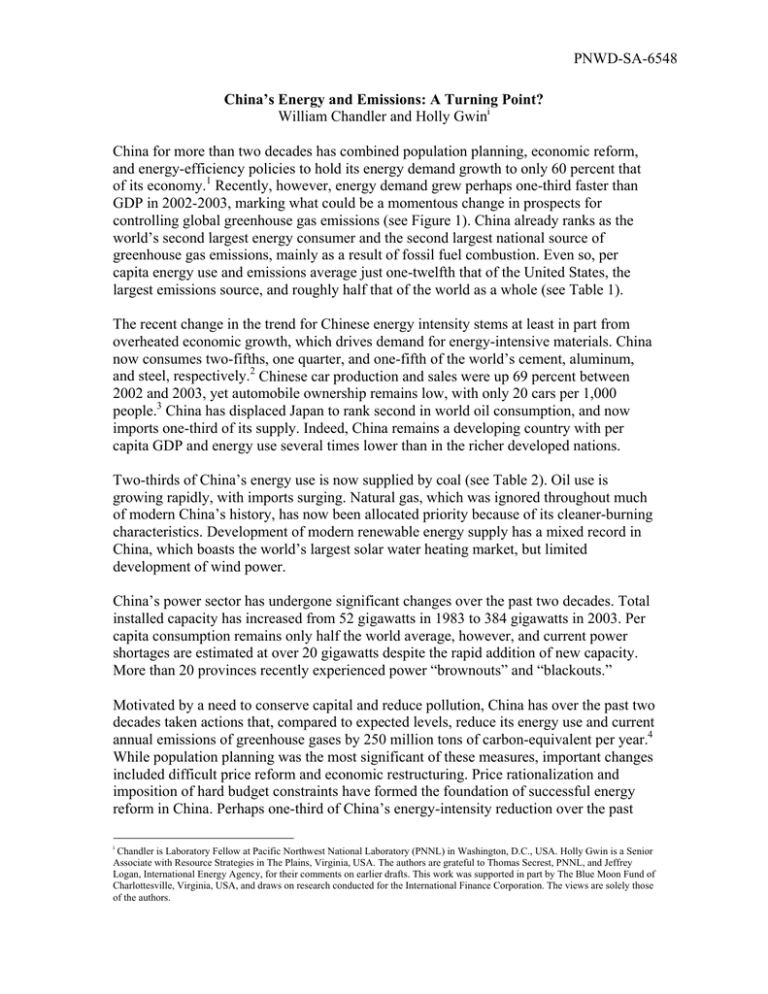

PNWD-SA-6548 China’s Energy and Emissions: A Turning Point? William Chandler and Holly Gwini China for more than two decades has combined population planning, economic reform, and energy-efficiency policies to hold its energy demand growth to only 60 percent that of its economy.1 Recently, however, energy demand grew perhaps one-third faster than GDP in 2002-2003, marking what could be a momentous change in prospects for controlling global greenhouse gas emissions (see Figure 1). China already ranks as the world’s second largest energy consumer and the second largest national source of greenhouse gas emissions, mainly as a result of fossil fuel combustion. Even so, per capita energy use and emissions average just one-twelfth that of the United States, the largest emissions source, and roughly half that of the world as a whole (see Table 1). The recent change in the trend for Chinese energy intensity stems at least in part from overheated economic growth, which drives demand for energy-intensive materials. China now consumes two-fifths, one quarter, and one-fifth of the world’s cement, aluminum, and steel, respectively.2 Chinese car production and sales were up 69 percent between 2002 and 2003, yet automobile ownership remains low, with only 20 cars per 1,000 people.3 China has displaced Japan to rank second in world oil consumption, and now imports one-third of its supply. Indeed, China remains a developing country with per capita GDP and energy use several times lower than in the richer developed nations. Two-thirds of China’s energy use is now supplied by coal (see Table 2). Oil use is growing rapidly, with imports surging. Natural gas, which was ignored throughout much of modern China’s history, has now been allocated priority because of its cleaner-burning characteristics. Development of modern renewable energy supply has a mixed record in China, which boasts the world’s largest solar water heating market, but limited development of wind power. China’s power sector has undergone significant changes over the past two decades. Total installed capacity has increased from 52 gigawatts in 1983 to 384 gigawatts in 2003. Per capita consumption remains only half the world average, however, and current power shortages are estimated at over 20 gigawatts despite the rapid addition of new capacity. More than 20 provinces recently experienced power “brownouts” and “blackouts.” Motivated by a need to conserve capital and reduce pollution, China has over the past two decades taken actions that, compared to expected levels, reduce its energy use and current annual emissions of greenhouse gases by 250 million tons of carbon-equivalent per year.4 While population planning was the most significant of these measures, important changes included difficult price reform and economic restructuring. Price rationalization and imposition of hard budget constraints have formed the foundation of successful energy reform in China. Perhaps one-third of China’s energy-intensity reduction over the past i Chandler is Laboratory Fellow at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) in Washington, D.C., USA. Holly Gwin is a Senior Associate with Resource Strategies in The Plains, Virginia, USA. The authors are grateful to Thomas Secrest, PNNL, and Jeffrey Logan, International Energy Agency, for their comments on earlier drafts. This work was supported in part by The Blue Moon Fund of Charlottesville, Virginia, USA, and draws on research conducted for the International Finance Corporation. The views are solely those of the authors. three decades has been due to price rationalization, and other elements of intensity reduction—economic restructuring and energy-efficiency policy interventions—would have been impossible without price reform. China’s Tenth “Five-Year Plan” (effective 2001-2005) continued and accelerated the long shift to market mechanisms to allocate energy and other resources. This Plan in theory assigned high priority to improving energy efficiency, even elevating its importance to equal that of energy development. But efforts to translate general statements of support for energy efficiency into effective, specific measures have lagged recently, especially as the economy shifted into high gear. The Chinese government, concerned that its policy tools are inadequate for current market conditions, is considering more-effective ways to promote energy efficiency and renewable energy in a market economy.5 Drafts of the “Eleventh Five Year Plan” advocate new or strengthened policies, including: ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Demand Side Management (DSM) and Integrated Resources Planning (IRP) Energy Management Company (EMC) businesses Government procurement policies for energy efficient products Voluntary agreements for energy conservation in selected sectors Industrial development of renewable energy The development of advanced renewable energy technologies, including wind power, biomass generation, and solar power, and Market demand for renewable energy through partnerships or collaboration between government and market players. Significantly, China has recently adopted a law to regulate automobile fuel economy in a manner similar to the U.S. corporate average fuel economy standards (CAFE). The measure will actually ban many fuel-inefficient sports utility vehicles or require them to improve fuel economy above U.S. passenger car levels. The law, when fully implemented in 2008, would increase the fleet fuel economy of Chinese cars to five miles per gallon more than the current U.S. car standard of 27.5 miles per gallon (8.5 liters per 100 km).6 Many emission mitigation opportunities consistent with economic development remain to be captured (see Figure 2). The main concern is that if energy-efficiency policies falter, Chinese energy demand could grow nearly four-fold by 2050.7 Economic restructuring, fuel switching, population planning, and other measures could dramatically slow demand growth and reduce China’s emissions trajectory. China’s energy policy makers appear to be at a turning point. Their impending choices will lead to slower, more-manageable growth in greenhouse gas emissions, or to rapid growth that could overwhelm domestic Chinese and international mitigation efforts. 20 15 GDP 10 5 Energy 0 -10 Figure 2: Potential Chinese Emissions Mitigation by Measure, 2000-2030 0.9 Billion Tons Carbon 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 Economic Restructuring Efficiency Technology Oil Natural Gas Nuclear Renewables 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 2000 Source: Chandler et al., 2002 2010 2020 2030 3 8 3 8 Source: Jeffrey Logan, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and International Energy Agency, private communication 2004. 0 20 9 19 9 19 8 19 3 -5 8 19 Percent Change from Previous Year Figure 1: Changing Energy Use vs GDP in China Table 1: Key Chinese Social and Economic Development Indicators Annual Energy-Related Carbon Emissions, 2001 (million tons) 868 Population (year 2003, millions) 1,292 Population Growth Rate (percent per year) 0.6 Based on Exchange Rate $1090 Per Capita GDP, 2003 Purchasing Power Parity $4890 GDP Growth Rate, 2003 (percent per year in constant local currency units) 9.1 Primary Energy Consumption (Gigajoules per Capita, 2003) 38 Electric Power Consumption (Kilowatt hours per capita, 2002) 1271 Persons without electricity (millions, 2002) 23 Per capita Greenhouse Gas Emissions (percent of U.S., 2001) 8.5 Sources: China Statistical Yearbook; OECD, World Bank Development Indicators; Beijing Energy Efficiency Center; Japan Institute of Energy Economics; China’s Statistical Communiqué 2003 On National Social-Economic Development; Chinese National Bureau of Statistics. Table 2: Chinese Energy Use by Type Total Energy Energy Consumption Mix (%) Consumption Coal Oil Natural Hydro & Year Billion Tons Coal Gas Nuclear Equivalent (EJ) 1980 0.6 (15 EJ) 72 21 3 4 1990 1.0 (24 EJ) 76 17 2 5 2002 1.5 (36 EJ) 66 24 3 8 Source: BECon, 2004. Endnotes 1. Technically, China’s GDP elasticity of energy demand has averaged roughly 0.6 for over 20 years. See William Chandler, Roberto Schaeffer, Zhou Dadi, PR Shukla, Fernando Tudela, Ogunlade Davidson, Sema Alpan-Atamer, Climate Change Mitigation in Developing Countries: Brazil, China, India, Mexico, South Africa, and Turkey, Pew Center on Global Climate Change, Washington, October 2002. 2. Jeffrey Logan, International Energy Agency, private communication, Beijing, April 2004. 3. Simon Romero, “China Demand and Weak Dollar May Support High Oil Price,” New York Times, 2 January 2004. 4. Chandler et al., Op. Cit. 5. Ren Long, Deputy Director-General, Department of Policy and Regulations, National Development and Reform Commission, “Supporting China’s Strategy for Sustainable Energy Development,” Terminal Tripartite Review Meeting, United Nations Development Program, Beijing, China, 12 December 2003. 6. New York Times, “China Set to Act on Fuel Economy,” 18 November 2003. 7. BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2003, available at www.bp.com.