working time and the future of work in canada a nova scotia gpi case

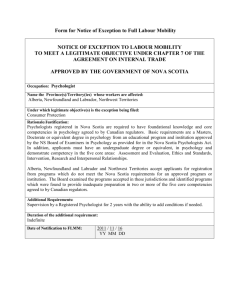

advertisement