arXiv:1403.7688v2 [math.DS] 19 Apr 2016

advertisement

![arXiv:1403.7688v2 [math.DS] 19 Apr 2016](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/018522421_1-2cb058aaf62549540c0bd6b7e673adda-768x994.png)

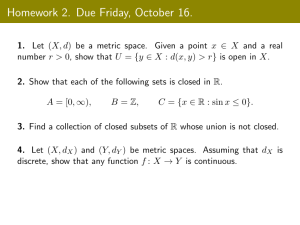

arXiv:1403.7688v1 [math.DS] 30 Mar 2014

Integrability of holonomy cocycle for singular

holomorphic foliations

Viêt-Anh Nguyên

April 1, 2014

Abstract

We study the holonomy cocycle associated with a holomorphic Riemann

surface foliation with a finite number of linearizable singularities. By accelerating the leafwise Poincaré metric near the singularities, we show that

the holonomy cocycle is integrable with respect to each harmonic probability measure directed by the foliation. As an application we establish the

existence of Lyapunov exponents as well as an Oseledec decomposition for

this cocycle.

Classification AMS 2010: Primary: 37A30, 57R30; Secondary: 58J35, 58J65,

60J65.

Keywords: holomorphic foliation, linearizable singularity, Poincaré metric, holonomy cocycle, harmonic measure, Lyapunov exponents.

1

Introduction

The dynamical and geometrical theory of holomorphic foliations has received

much attention in the past few years. The holonomy cocycle (or equivalently,

the normal derivative cocycle) of a foliation is a very important object which

reflects dynamical, topological as well as geometrical and analytic aspects of the

foliation. Exploring this object allows us to understand more about the foliation

itself.

In this paper we investigate the holonomy cocycle of a singular holomorphic

foliation F by hyperbolic Riemann surfaces in a Hermitian compact complex

manifold of arbitrary dimension. Under some reasonable assumption on F and

by accelerating the leafwise Poincaré metric near the singularities while keeping

the metric complete and of bounded geometry, we show that the holonomy cocycle is integrable with respect to each harmonic probability measure directed

by the foliation. We also show an evidence that this acceleration is necessary to

1

ensure the integrability. As a by-product we establish the existence of Lyapunov

exponents as well as an Oseledec decomposition for this cocycle.

There are two main sources of examples of holomorphic foliations by Riemann

surfaces. The first one consists of holomorphic foliations by curves in the complex

projective space Pk (in which case there are always singularities) or in algebraic

manifolds. The foliations of the second source are those obtained by the process of

suspension. For a recent account on the subject as well as numerous illuminating

examples the reader is invited to consult the survey articles by Fornæss-Sibony

[15], Ghys [19], Hurder [20] and textbooks [5, 6, 29]. In the subsequent subsections

we lay out the set-up of our problem. This preparation enable us to state the

main result at the end of this section.

1.1

Foliations, singularities and Poincaré metric

Let M be a complex manifold of dimension k. A holomorphic foliation by Riemann

surfaces (M, F ) on M is the data of a foliation atlas with charts

Φi : Ui → Bi × Ti .

Here, Ti is a domain in Ck−1 , Bi is a domain in C, Ui is a domain in M, and Φi

is biholomorphic, and all the changes of coordinates Φi ◦ Φ−1

j are of the form

(x, t) 7→ (x′ , t′ ),

x′ = Ψ(x, t),

t′ = Λ(t).

The open set Ui is called a flow box and the Riemann surface Φ−1

i {t = c} in

Ui with c ∈ Ti is a plaque. The property of the above coordinate changes insures

that the plaques in different flow boxes are compatible in the intersection of the

boxes. Two plaques are adjacent if they have non-empty intersection.

A leaf L is a minimal connected subset of M such that if L intersects a plaque,

it contains that plaque. So a leaf L is a Riemann surface immersed in M which

is a union of plaques. A leaf through a point x of this foliation is often denoted

by Lx . A transversal is a complex submanifold of X which is transverse to the

leaves of F .

A holomorphic foliation by Riemann surfaces with singularities is the data

(M, F , E), where M is a complex manifold, E a closed subset of M and (M \

E, F ) is a holomorphic foliation by Riemann surfaces. Each point in E is said

to be a singular point, and E is said to be the set of singularities of the foliation.

We always assume that M \ E = M, see e.g. [11, 14] for more details. If M is

compact, then we say that the foliation (M, F , E) is compact.

Let (M, F , E) be a foliation. We denote by CF the sheaf of functions f defined

and compactly supported on M \ E which are leafwise smooth and transversally

continuous, that is, which are smooth along the leaves and all whose leafwise

∂ α+β f

derivatives ∂x

α ∂ x̄β in foliation charts are continuous in (x, t).

2

We say that a vector field F on Ck is generic linear if it can be written as

F (z) =

k

X

λj zj

j=1

∂

∂zj

where λj are non-zero complex numbers. The integral curves of F define a foliation on Ck . The condition λj 6= 0 implies that the foliation has an isolated

singularity at 0. Consider a foliation (M, F , E) with a discrete set of singularities E. We say that a singular point e ∈ E is linearizable if there is a (local)

holomorphic coordinates system of M on an open neighborhood Ue of e on which

the leaves of (M, F , E) are integral curves of a generic linear vector field. Such

neighborhood Ue is called a singular flow box of e.

For the sake of simplicity, we adopt the following terminology throughout

the article: A foliation means exactly a holomorphic foliation (M, F , E) in a

Hermitian compact complex manifold (M, gM ) with a finite set E of (linearizable)

singularities.

Throughout the article let D denote the unit disc in C and let gP be the

Poincaré metric on D, defined by

gP (ζ) :=

2

idζ ∧ dζ,

(1 − |ζ|2)2

ζ ∈ D.

A leaf L of the foliation is said to be hyperbolic if it is a hyperbolic Riemann

surface, i.e., it is uniformized by D. For a hyperbolic leaf Lx , let φx : D → Lx be

a universal covering map with φx (0) = x. Note that φx is unique up to a rotation

around 0 ∈ D. Then, the Poincaré metric gP on D induces, via φx , the Poincaré

metric on Lx which depends only on the leaf. The latter metric is given by a

positive (1, 1)-form on Lx that we also denote by gP . The foliation is said to be

hyperbolic if its leaves are all hyperbolic.

Consider the function η : M \ E → [0, ∞] defined by

η(x) := sup {kDφ(0)k : φ : D → Lx holomorphic such that φ(0) = x} .

Here, for the norm of the differential Dφ we use the Poincaré metric on

the Hermitian metric gM on Lx .

Following a recent joint-work with Dinh and Sibony [13], the foliation

to be Brody hyperbolic if there is a constant c0 > 0 such that η(x) ≤ c0

x ∈ M \ E.

For simplicity we still denote by gM the Hermitian metric on leaves

foliation (M \ E, F ) induced by the ambient Hermitian metric gM . We

the following relation between gM and the Poincaré metric gP on leaves

gM = η 2 gP .

3

D and

is said

for all

of the

record

(1)

It is clear that if the foliation is Brody hyperbolic then it is hyperbolic. Conversely, the Brody hyperbolicity is a consequence of the non-existence of holomorphic non-constant maps C → M such that out of E the image of C is locally

contained in leaves, see [15, Theorem 15]. Moreover, Lins Neto proves in [22]

that for every holomorphic foliation of degree larger than 1 in Pk , with nondegenerate singularities, there is a smooth metric with negative curvature on its

tangent bundle, see also Glutsyuk [18]. Hence, these foliations are Brody hyperbolic. On the other hand, thanks to Lins Neto et Soares [25] we know that a

generic holomorphic foliations in Pk with a given degree d is with non-degenerate

singularities. Consequently, holomorphic foliations in Pk with a given degree

d > 1 are generically Brody hyperbolic.

1.2

Leafwise metrics and harmonic measures

Let (M, F , E) be a hyperbolic foliation in a Hermitian complex manifold (M, gM ).

A leafwise metric is a tensor metric defined on all leaves of the foliation which

depends measurably on plaques in each flow box. We say that a leafwise metric

g is complete and of bounded geometry if the universal cover of each leaf of F is

complete and of uniformly bounded geometry with respect to g. The assumption

of uniformly bounded geometry means that there are real numbers c, r > 0, such

ex

that for every point x ∈ M \ E, the injectivity radius of the universal cover L

(of the leaf Lx ) is ≥ r and the Gaussian curvature of the leaf Lx at x belongs to

the interval [−c, c].

Let g be a leafwise metric which is complete and of bounded geometry. g

induces the corresponding g-Laplacian ∆ = ∆g on leaves. A positive finite Borel

measure m on M is said to be g-harmonic if

Z

∆udm = 0

M

for all functions u ∈ CF .

A subset X ⊂ M \ E is said to be leafwise saturated if x ∈ X implies that the

whole leaf Lx is contained in X.

1.3

Accelerating metrics

Let (M, F , E) be a foliation in a Hermitian compact complex manifold (M, gM ).

Assume that E ⊂ M is an (eventually empty) finite set. To each leafwise metric

g we associate a unique function ξ : M \ E → (0, ∞) such that g = ξ 2 gP on

leaves, where gP is as usual the leafwise Poincaré metric.

Definition 1.1. We say that a leafwise metric g = ξ 2 gP is accelerating if the

following conditions are satisfied:

(i) ξ is a continuous function.

4

(ii) g is complete and of bounded geometry.

(iii) for every e ∈ E, there exist an open neighborhood U = Ue of e with U ∩ E =

{e}, a function ρ = ρe : (0, ∞) → (0, ∞) and a constant c = ce > 0 such that:

(iii-a) c−1 ρ(dist(x, e)) ≤ ξ(x) ≤ cρ(dist(x, e)) for each x ∈ U;

′

c

≤ −r log

for all r > 0 small enough;

(iii-b) |ρρ2(r)|

(r)

r

(iii-c) the following integrability conditions are satisfied:

Z 1 2

Z 1

ρ (r)dr

dr

<∞

and

< ∞.

2

2

0 r(log r)

0 ρ (r)r log r

Roughly speaking, an accelerating metric has two behaviors. Far from the

singularities it behaves like the Poincaré metric, whereas near the singularities it

“accelerates” in comparison with the latter one (that is, ξ(x) → ∞ as x → E),

and this acceleration is controlled. Each function ρ of type ρ(r) := (− log r)δ for

r > 0 small enough, where δ is any number in (0, 1/2), satisfies the growth conditions (iii-b) and (iii-c). Using this observation we will construct in Subsection

2.1 below a large class of accelerating metrics.

1.4

Sample-path spaces and holonomy cocycle

Let (M, F , E) be a hyperbolic foliation, where (M, gM ) is a Hermitian complex

manifold of dimension k. Let g be a leafwise metric which is complete and of

bounded geometry. Let Ω := Ω(M, F , E) be the space consisting of all continuous

paths ω : [0, ∞) → M with image fully contained in a single leaf. This space

is called the sample-path space associated to (M, F , E). Observe that Ω can be

thought of as the set of all possible paths that a Brownian particle, located at

ω(0) at time t = 0, might follow as time progresses. For each x ∈ M \ E, let

Ωx = Ωx (M, F , E) be the space of all continuous leafwise paths starting at x in

(M, F , E), that is,

Ωx := {ω ∈ Ω : ω(0) = x} .

The theory of Brownian motion allows us to construct a natural probability

measure Wx on Ωx , using that Lx is endowed with the metric g|Lx . This is the

Wiener measure at x. A measure theory on Ω will be discussed thoroughly in

Subsection 2.3 below. In particular, to each harmonic probability measure µ on

M \ E, we associate a canonical probability measure µ̄ on Ω using formula (8)

below.

Now we define the holonomy cocycle of the foliation (M, F , E). Let T (F )

be the tangent bundle to the leaves of the foliation, i.e., each fiber Tx (F ) is the

tangent space Tx (Lx ) for each point x ∈ M \ E. The normal bundle N(F ) is,

by definition, the quotient of T (M) by T (F ), that is, the fiber Nx (F ) is the

quotient Tx (M)/Tx (F ) for each x ∈ M \ E. Observe that the metric gM on

M induces a metric (still denoted by gM ) on N(F ). For every transversal S at

5

a point x ∈ M, the tangent space Tx (S) is canonically identified with Nx (F )

through the composition Tx (S) ֒→ Tx (M) → Tx (M)/Tx (F ).

For every x ∈ M \ E and ω ∈ Ωx and t ∈ R+ , let holω,t be the holonomy map

along the path ω|[0,t] from a fixed transversal S0 at ω(0) to a fixed transversal St at

ω(t). Using the above identification, the derivative Dholω,t : Tω(0) (S0 ) → Tω(t) (St )

induces the so-called holonomy cocycle H(ω, t) : Nω(0) (F ) → Nω(t) (F ). The last

map depends only on the path ω|[0,t] , in fact, it depends only on the homotopy

class of this path. In particular, it is independent of the choice of transversals S0

and St .

1.5

Statement of the main result

Now we are in the position to state our main result.

Main Theorem. Let (M, F , E) be a holomorphic Brody hyperbolic foliation

with a finite number of linearizable singularities in a Hermitian compact complex

manifold (M, gM ). Let H be the holonomy cocycle of the foliation. Let g be an

accelerating leafwise metric. Let µ be a g-harmonic probability measure. Consider

the function F : Ω → R+ defined by

F (ω) := sup max{| log kH(ω, t)k|, | log kH−1 (ω, t)k|},

ω ∈ Ω.

t∈[0,1]

Then F is µ̄-integrable.

Some remarks are in order. As mentioned in Subsection 1.3 above, accelerating metrics exist in abundance. On the other hand, Theorem 2.3 below exhibits a

one-to-one correspondence between the convex cone of positive g-harmonic finite

measures µ and the convex cone of positive harmonic currents T on M. Note that

the latter cone is independent of the choice of a metric g and that it is always

nonempty. This, combined with the discussion concluding Subsection 1.1, implies

that the the Main Theorem applies to every generic foliation in Pk with a given

degree d > 1.

The article is organized as follows. In Section 2 below we introduce a large

family of accelerating metrics. A quick discussion on the heat diffusions as well as

the measure theory on sample-path spaces will also be given in that section. This

preparation serves as the background for what follows. Section 3 below is devoted

to an analytic study on the holonomy cocycle. The proof of the main result will

be provided in Section 4 below. A remark showing that the acceleration of the

leafwise Poincaré metric is necessary concludes that section. As an application of

the main result, we present, in the last section, an Oseledec multiplicative ergodic

theorem for the holonomy cocycle. In particular, we define Lyapunov exponents

of this cocycle.

Acknowledgement.

The author would like to thank Nessim Sibony (University of Paris 11) and Tien-Cuong Dinh (University of Paris 6) for interesting

6

discussions. The paper was partially prepared during the visit of the author at

the Max-Planck Institute for Mathematics in Bonn. He would like to express his

gratitude to these organizations for hospitality and for financial support.

2

2.1

Preparatory results

Accelerating metrics: examples

First we give a description of the local model for linearizable singularities. Consider the foliation (Dk , F , {0}) which is the restriction to Dk of the foliation

associated to the vector field

F (z) =

k

X

j=1

λj zj

∂

∂zj

with λj ∈ C∗ . The foliation is singular at the origin. We use here the Euclidean

metric on Dk . Write λj = sj + itj with sj , tj ∈ R. For x = (x1 , . . . , xk ) ∈ Dk \ {0},

define the holomorphic map ϕx : C → Ck \ {0} by

λ1 ζ

λk ζ

for ζ ∈ C.

ϕx (ζ) := x1 e , . . . , xk e

It is easy to see that ϕx (C) is the integral curve of F which contains ϕx (0) = x.

k

Write ζ = u + iv with u, v ∈ R. The domain Πx := ϕ−1

x (D ) in C is defined by

the inequalities

sj u − tj v < − log |xj | for j = 1, . . . , k.

So, Πx is a convex polygon which is not necessarily bounded. It contains 0 since

bx := ϕx (Πx ).

ϕx (0) = x. The leaf of F through x contains the Riemann surface L

In particular, the leaves in a singular flow box are parametrized in a canonical

way using holomorphic maps ϕx : Πx → Lx , where Πx is as above C.

Now let (M, F , E) be a Brody hyperbolic foliation on a Hermitian compact

complex manifold (M, gM ). Assume as usual that E is finite and all points of E

are linearizable. Let dist be the distance on M induced by the ambient metric

gM . We only consider flow boxes which are biholomorphic to Dk . For regular flow

boxes, i.e., flow boxes outside the singularities, the plaques are identified with

the discs parallel to the first coordinate axis. Singular flow boxes are identified to

their models as described above. For each singular point e ∈ E, we fix a singular

flow box Ue such that 2Ue ∩ 2Ue′ = ∅ if e 6= e′ . We also cover M \ ∪e∈E Ue by

regular flow boxes Ui which are fine enough. In particular, each Ui is contained

in a larger regular flow box 2Ui with 2Ui ∩ E = ∅. In this section we suppose

that the ambient metric gM coincides with the standard Euclidean metric on each

singular flow box 2Ue ≃ 2Dk . For x = (x1 , . . . , xk ) ∈ Ck , let kxk be the standard

Euclidean norm of x.

7

We record here following crucial result which gives a precise estimate on the

function η introduced in (1).

Lemma 2.1. Under the above hypotheses and notation, there exists a constant

c > 1 such that η ≤ c on M, η ≥ c−1 outside the singular flow boxes 41 Ue and

c−1 s log⋆ s ≤ η(x) ≤ cs log⋆ s

for x ∈ M \ E and s := dist(x, E). Here log⋆ (·) := 1 + | log(·)| is a log-type

function.

This result has been proved in Proposition 3.3 in [13].

Given a leafwise metric g, there exists a unique function ξ : M \ E → (0, ∞)

such that

g(x) = ξ 2 (x)gP (x),

x ∈ M \ E.

(2)

The next theorem exhibits an explicit family of accelerating metrics.

Theorem 2.2. Let ξ : M \ E → (0, ∞) be a continuous and leafwise smooth

function. Assume that for each e ∈ E, there exists a singular flow box Ue such that

(Ue , e) ≃ (Dk , 0) and that ξ(x) = (− log kxk)δ , x ∈ Ue , for some 0 < δ = δe < 1/2.

Then the leafwise metric g defined by (2) is accelerating.

Proof. It is straightforward to check condition (i) and (iii) of Definition 1.1.

Therefore, it remains to check condition (ii) of this definition. Since there is

a constant c > 0 such that g ≥ cgP , the completeness of all leaves follows.

Next, we will show that the Gaussian curvature of all leaves in singular flow

boxes are uniformly bounded. Clearly, we only need to this check this for points

near the singularities. To this end fix a point x ∈ Dk \ {0}. Consider the locally

biholomorphic map ϕx : Πx → Lx defined as above. Note that Πx is a convex

domain containing 0. We want to estimate the Gaussian curvatures of the leaf Lx

near the point x using ϕx . For ζ in a small neighborhood of 0 in C, write

(ϕ∗x g)(ζ) = ξ 2 (ϕx (ζ)) · (ϕ∗x gP )(ζ) ≡ ξ 2(ϕx (ζ)) · τ 2 (ζ).

By pulling g back, via ϕx to an open neighborhood of 0 in C The Gaussian

curvature of (Lx , g) at a point ϕx (ζ) for ζ small enough is

−i∂∂ log (ξ 2 (ϕx (ζ)) −i∂∂ log (τ 2 (ζ))

−i∂∂ log (ξ 2(ϕx (ζ))τ 2 (ζ))

=

+ 2

.

ξ 2 (ϕx (ζ)τ 2 (ζ)

ξ 2 (ϕx (ζ)τ 2 (ζ)

ξ (ϕx (ζ)τ 2(ζ)

Since the Gaussian curvature of (Lx , gP ) is −1 and ϕ∗x gP = τ 2 , we infer that

−

i∂∂ log τ 2 (ζ)

= −1.

τ 2 (ζ)

8

(3)

On the other hand, using the explicit expression of ϕx and applying Lemma 2.1

we obtain that

1

· (ϕ∗x gM )(ζ)

η(ϕx (ζ))

1

1

1

· kϕx (ζ)k ≈ ≈

.

≈

− log kxk

kϕx (ζ)k log kϕx (ζ)k

log kϕx (ζ)k

τ (ζ) =

Using that

(ξ ◦ ϕx )(ζ) = − log k(x1 eλ1 ζ , . . . , xk eλk ζ )k

δ

δ

≈ − log kxk ,

a straightforward computation gives that

i∂∂ log(ξ ◦ ϕx )2 (ζ) ≈ (− log kϕx (ζ)k)−2 ≈ (− log kxk)−2 .

Inserting the last three estimates into (3), we infer that the curvature of (Lx , g)

at a point ϕx (ζ) for ζ small enough tends to 0 uniformly as kxk → 0.

Next, we will show that the injectivity radius of each leaf is uniformly bounded

from below by a constant r0 > 0. Recall that the leaves of the foliations are

complete and of uniformly bounded geometry with respect to g. Therefore, by a

result of Cheeger, Gromov and Taylor [9] we only need to show that there are

some constants c0 , r0 > 0 such that for every x ∈ M \ E,

Volg (Dg (x, r0 )) > c0 ,

(4)

where Dg (x, r) is the disc centered at x with g-radius r on Lx , and Volg is the

g-volume measure on Lx . Clearly, we only need to check this for points x near

the singularities. To this end fix a point x ∈ Dk \ {0}. Consider the locally

biholomorphic map ϕx : Πx → Lx defined as above. Note that Πx is a convex

domain containing 0 and that the Euclidean distance from 0 to ∂Πx is of order

− log kxk. Using the approximation for τ and ξ ◦ ϕx given above, we can show

that there are constants c1 , c2 , r > 0 such that

ϕx D(c1 (− log kxk)1−δ ) ⊂ Dg (x, r0 ) ⊂ ϕx D(c2 (− log kxk)1−δ ) ,

where ∆(ρ) denotes the disc (in C) centered at 0 with radius ρ. Moreover, we can

even show that, for ζ ∈ D(c(− log kxk)δ ) for any fixed c > 0,

(ϕ∗x g)(ζ) = ξ 2 (ϕx (ζ)) · τ 2 (ζ) ≈ (− log kxk)−2+2δ .

Consequently, there is a constant c > 0 such that

Z

1−δ

Volϕ∗x g D(c1 (− log kxk) ) ≥

(− log kxk)−2+2δ idζ ∧ dζ̄ ≥ c,

|ζ|≤c1 (− log kxk)1−δ

proving (4). Hence, the proof is thereby completed.

9

2.2

Heat diffusions and harmonic currents versus harmonic measures

Let (M, F , E) be a hyperbolic foliation (M, F , E) in a Hermitian compact complex manifold (M, gM ). Consider a leafwise metric g which is complete and of

bounded geometry. For every point x ∈ M \ E consider the heat equation on Lx

∂p(x, y, t)

= ∆y p(x, y, t),

∂t

lim p(x, y, t) = δx (y),

t→0

y ∈ Lx , t ∈ R+ .

Here δx denotes the Dirac mass at x, ∆y denotes the g-Laplacian ∆g with respect

to the variable y, and the limit is taken in the sense of distribution, that is,

Z

p(x, y, t)φ(y)dVolx (y) = φ(x)

lim

t→0+

Lx

for every smooth function φ compactly supported in Lx , where Volx denotes the

volume form on Lx induced by g|Lx .

The smallest positive solution of the above equation, denoted by p(x, y, t),

is called the heat kernel. Such a solution exists because Lx is complete and of

bounded geometry (see, for example, [8, 6]). The heat kernel gives rise to a

one parameter family {Dt : t ≥ 0} of diffusion operators defined on bounded

functions on M \ E :

Z

p(x, y, t)f (y)dVolx (y),

x ∈ M \ E.

(5)

Dt f (x) :=

Lx

We record here the semi-group property of this family: D0 = id and Dt+s =

Dt ◦ Ds for t, s ≥ 0.

Let CF1 denote the space of forms of bidegree (1, 1) defined on leaves of the

foliations and compactly supported on M \ E which are leafwise smooth and

transversally continuous. A form α ∈ CF1 is said to be positive if its restriction

to every plaque is a positive (1, 1)-form in the usual sense. A positive harmonic

current T on the foliation is a linear continuous form on CF1 which verifies ∂∂T =

0 in the weak sense (namely T (∂∂f ) = 0 for all f ∈ CF ), and which is positive

(namely, T (α) ≥ 0 for all positive forms α ∈ CF1 ). The existence of such a

current has been established by Berndtsson-Sibony [1] and Fornæss-Sibony [15].

The extension of T by zero through E, still denoted by T, is a positive ∂∂-closed

current on M. The total mass of the measure T ∧ gM is always finite. For any

leafwise metric g, the g-mass of a positive harmonic current T is, by definition,

the total mass of the measure T ∧ g.

A positive finite measure µ on the σ-algebra of Borel sets in M is said to be

ergodic if for every leafwise saturated measurable set Z ⊂ M, µ(Z) is equal to

either µ(M) or 0. A positive harmonic currents T is said to be extremal if it is

an extremal point in the convex cone of positive harmonic currents.

The class of accelerating metrics enjoys the following important properties.

10

Theorem 2.3. Let (M, F , E) be a hyperbolic foliation and g an accelerating

(leafwise) metric.

1) Then, for each positive harmonic current T, the g-mass of T is finite.

2) The relation µ = T ∧g is a one-to-one correspondence between the convex cone

of (resp. extremal) positive harmonic currents T and the convex cone of (resp.

ergodic) positive harmonic finite measures µ.

3) All positive harmonic finite measures µ are Dt -invariant, i.e,

Z

Z

Dt f dµ =

f dµ,

f ∈ L1 (M, µ).

M

M

Proof. In an arbitrarily fixed singular flow box Ue ≃ (2D)k , the metric gM coin2

cides with the standard Kähler metric i∂∂kzk2 . Recall that g = ηξ 2 gM on leaves

in Dk \ {0}. Moreover, by Lemma 2.1, η(a) & kak| log kak|. Let T be a positive

∂∂-closed current on (2D)k such that µ = T ∧ g. We only have to show that the

integral on the the ball B1/2 , with respect to the measure T ∧Ri∂∂kzk2 , of the

radial function β(r) := r −2 | log r|−2 ρ(r)2 is finite. Let m(r) := Br T ∧ i∂∂kzk2 .

Since the Lelong number of T at 0 exists and is finite, we have m(r) . r 2 (see

Lemma 2.4 in [11]). Using an integration by parts, the considered integral is

equal, up to finite constants, to

Z 1

−

m(r)β ′ (r)dr.

0

Using an integration by part again, we can check that the last integral is finite

R 1 ρ(r)2 dr

< ∞. But this condition is always satisfied according to the first

when 0 r(log

r)2

integrability condition (iii-c) of the accelerating metric g. This proves assertion

1).

Using assertion 1) and arguing as in the proof of Proposition 5.1 in [11],

assertion 2) follows.

Let T be the unique harmonic current, given by assertion 2), such that µ =

T ∧ g. Since ξ is continuous outside E and ξ(x) → ∞ as x → E, there is a

constant c > 0 such that g ≥ cgP . Hence, T is g-regular in the sense of [11, p.

361]. This, together with the fact that µ is finite, allows us to apply Theorem

6.4 in [11]. Hence, assertion 3) follows.

2.3

Measure theory on sample-path spaces

In this subsection we follow the expositions given in Subsection 2.2, 2.4 and 2.5 in

[23] (see also [6]). Recall first the following terminology. A σ-algebra A on a set

Ω is a family of subsets of Ω such that Ω ∈ A , and X \ AT

∈ A for each A ∈ A ,

and that A is stable under countable intersections, i.e., ∞

n=1 An ∈ A for any

∞

sequence (An )n=1 ⊂ A . The σ-algebra generated by a family S of subsets of Ω

is, by definition, the smallest σ-algebra containing S .

11

Let (M, F , E) be a hyperbolic foliation endow with a accelerating (leafwise)

metric g. Let Ω := Ω(M, F , E) be the associated sample-path space. The first

goal of this subsection is to introduce a σ-algebra A on Ω and to construct, for

each point x ∈ M \ E, the so-called Wiener probability measure Wx on Ω.

A cylinder set (in Ω) is a set of the form

C = C({ti , Bi } : 1 ≤ i ≤ m) := {ω ∈ Ω : ω(ti ) ∈ Bi ,

1 ≤ i ≤ m} .

where m is a positive integer and the Bi are Borel subsets of M \ E, and 0 ≤ t1 <

t2 < · · · < tm is a set of increasing times. In other words, C consists of all paths

ω ∈ Ω which can be found within Bi at time ti . For each point x ∈ M \ E, let

(6)

Wx (C) := Dt1 (χB1 Dt2 −t1 (χB2 · · · χBm−1 Dtm −tm−1 (χBm ) · · · ) (x),

where C := C({ti , Bi } : 1 ≤ i ≤ m) as above, χBi is the characteristic function

of Bi and Dt is the diffusion operator given by (5).

Let Af= Af(M, F , E) be the σ-algebra generated by all cylinder sets. It can

be proved that Wx extends to a probability measure on Af. Summarizing what

has been done so far, we have constructed, for each x ∈ M \ E, a probability

measure Wx on the measure space (Ω, Af).

f) of a foliation (M, F , E) is, in some sense, its

f, F

The covering foliation (M

universal cover. We give here its construction. For every leaf L of (M, F , E) and

every point x ∈ L, let π1 (L, x) denotes as usual the first fundamental group of

all continuous closed paths γ : [0, 1] → L based at x, i.e. γ(0) = γ(1) = x. Let

[γ] ∈ π1 (L, x) be the class of a closed path γ based at x. Then the pair (x, [γ])

f). Thus the set of points of M

f, F

f is well-defined. The

represents a point in (M

e passing through a given point (x, [γ]) ∈ M

f, is by definition, the set

leaf L

e := {(y, [δ]) : y ∈ Lx , [δ] ∈ π1 (L, y)} ,

L

which is the universal cover of Lx . We put the following topological structure on

f by describing a basis of open sets. Such a basis consists of all sets N (U, α),

M

U being an open subset of M \ E and α : U × [0, 1] → M being a continuous

function such that αx := α(x, ·) is a closed path in Lx based at x for each x ∈ U,

and

N (U, α) := {(x, [αx ]) : x ∈ U} .

f → M \ E is defined by π(x, [γ]) := x. It is clear that π is

The projection π : M

locally homeomorphic and is a leafwise map. By pulling-back the foliation atlas

of (M, F , E) as well as the metric g via π, we obtain a natural foliation atlas for

f) endowed with the leafwise metric π ∗ g. Denote by Ω

f).

f, F

e the space Ω(M

f, F

(M

f. Recall that Ωx

Let x ∈ M \ E and x̃ an arbitrary point in π −1 (x) ⊂ M

is the space of all paths ω in Ω starting at x, i.e., ω(0) = x. Analogously, let

12

f) be the space of all paths in Ω

e x̃ = Ωx̃ (M

f, F

e starting at x̃. Every path ω ∈ Ωx

Ω

e x̃ in the sense that π(ω̃) = ω. In what follows this

lifts uniquely to a path ω̃ ∈ Ω

e x̃ . So π(π −1 (ω)) = ω, ω ∈ Ωx .

bijective lifting is denoted by πx̃−1 : Ωx → Ω

x̃

Definition 2.4. Let A = A (M, F , E) be the σ-algebra generated by all sets of

following family

n

o

e

π ◦ à : cylinder set à in Ω ,

where π ◦ Ã := {π ◦ ω̃ : ω̃ ∈ Ã}.

Observe that Af⊂ A and that the equality holds if every leaf of the foliation

is homeomorphic to the disc D.

Now we construct a family {Wx }x∈M \E of probability Wiener measures on

(Ω, A ). Let x ∈ M \ E and C an element of A . Then we define the so-called

Wiener measure

Wx (C) := Wx̃ (πx̃−1 C),

(7)

where x̃ is an arbitrary point in π −1 (x), and

πx̃−1 (C) := πx̃−1 ω : ω ∈ C ∩ Ωx .

Given a probability measure µ on M \ E, consider the measure µ̄ on (Ω, A )

defined by

Z Z

dWx dµ(x),

B ∈A.

(8)

µ̄(B) :=

X

ω∈B∩Ωx

The measure µ̄ is called the Wiener measure with initial distribution µ. The

following result has been proved in Proposition 2.12 in [23].

Proposition 2.5. We keep the above hypotheses and notation.

(i) The value of Wx (C) defined in (7) is independent of the choice of x̃. Moreover,

Wx is a probability measure on (Ω, A ).

(ii) µ̄ given in (8) is a probability measure on (Ω, A ).

3

Holonomy cocycles

Observe that the validity of the Main Theorem does not depend on the choice of

′

an ambient metric gM . Indeed, given another ambient metric gM

, the compactness

−1

′

of M implies the existence of a constant c > 0 such that c gM ≤ gM

≤ gM .

Consequently, we can show that there is a constant c > 0 such that

|F (ω) − F ′ (ω)| < c,

ω ∈ Ω,

where F (resp. F ′ ) denotes the function F defined in the Main Theorem with

′

respect to the metric gM (resp. gM

). Hence, by Theorem 2.3, F is µ̄-integrable if

13

and only if F ′ is µ̄-integrable, proving our previous assertion. Therefore, we may

suppose without loss of generality that the ambient metric gM coincides with the

standard Euclidean metric on each singular flow box 2Ue ≃ 2Dk . By the same

reason, we also assume that the function ξ is radial near each singular point, that

is, ξ(x) = ρ(dist(x, e)), x ∈ Ue , for each e ∈ E.

For every x ∈ M \ E let Tx be a codimension 1 (complex) submanifold of M

that is orthogonal to the leaf Lx at x. When x in a singular flow box Ue ≃ Dk , we

may choose Tx as the hyperplane which is gM -orthogonal to the tangent space of

Lx at x, that is,

Tx := x + u : u ∈ Ck , hu, λxi = 0 .

Here, for x = (x1 , . . . , xk ) and y = (y1 , . . . , yk ) ∈ Ck , we write

λx := (λ1 x1 , . . . , λk xk ) and hx, yi :=

k

X

xj ȳj .

j=1

For every x ∈ M \ E and y in a small simply connected plaque P passing through

x, let holx,y be the holonomy map holω,t where ω ∈ Ω is a path starting at x

such that ω|[0,t] ⊂ P and ω(t) = y. Since P is simply connected, holx,y does not

depend on the choice of any ω and t. So Dholx,y : Nx (F ) → Ny (F ). For every

x ∈ M \ E, let

D log H(x, ·)u :=

lim

y→x, y∈Lx

1

kDholx,y (u)k

log

,

dist(y, x)

kuk

u ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0},

and

kD log H(x, ·)k :=

sup

|D log H(x, ·)u|,

u∈Nx (F )\{0}

where k · k denotes as usual the gM -norm. We have the following result.

Lemma 3.1. There exists a constant c > 0 such that for every x ∈ M \ E,

kD log H(x, ·)k ≤

c

.

dist(x, E)

Proof. The proof is based on the following homothetic property

Dholtx,ty (tu) = tDholx,y (u),

u ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0},

(9)

where x, y ∈ Dk \ {0}, y in a simply connected small plaque passing through x,

t > 0 such that tx, ty ∈ Dk .

Taking for granted identity (9), we will complete the proof of the lemma as

follows. First observe that there is a constant c > 0 such that

[

kD log H(x, ·)k ≤ c,

x∈M\

1/2Ue .

(10)

e∈E

14

Indeed, (10)Sholds since holx,y is smooth with respect to the parameters (x, y) and

the set M \ e∈E 1/2Ue is compact. So (10) implies the lemma since dist(x, E) ≥

1/2 when x is in this set.

Therefore, it remains to us to consider the case where x ∈ 1/2Ue ≃ (1/2D)k

1

. Applying identity (9) and noting that y ∈ Lx if

for some e ∈ E. Set t := 2kxk

and only if ty ∈ Ltx , we infer that

1

kDholtx,ty (tu)k

log

y→x, y∈Lx kty − txk

ktuk

kDholx,y (u)k

1

1

1

lim

log

= D log H(x, ·)u.

=

y→x,

y∈L

t

kuk

t

x dist(y, x)

D log H(tx, ·)tu =

lim

Hence,

1

D log H(tx, ·)tu.

(11)

2kxk

S

Since ktxk = 1/2, it follows that tx 6∈ M \ e∈E 1/2Ue . Consequently, by (10)

we get that |D log A (tx, ·)tu| ≤ c. This, combined with equality (11), implies the

lemma in this last case.

To complete the lemma it suffices to show identity (9). Let x, y ∈ Dk \ {0}

and t > 0 as in identity (9). There exists ǫ > 0 such that holx,y is well-defined

and holomorphic on {u ∈ u ∈ Ck : kuk < ǫ/2 and x + u ∈ Tx }. Observe that

D log H(x, ·)u =

holtx,ty (tx + tsu) = tholx,y (x + su),

s ∈ D,

since holx,y (x + su) ∈ Ty implies that tx + tsu and tholx,y (x + su) are in the same

leaf and that tholx,y (x + su) ∈ Tty . Consequently, for u ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0} we obtain

that

1

Dholtx,ty (tu) = lim kholtx,ty (tx + tsu) − holtx,ty (tx)k

s→0 s

1

= t · lim kholx,y (x + su) − holx,y (x)k = tDholx,y (u),

s→0 s

which proves (9).

In the remaining part of the section we investigate the holonomy cocycle when

we travel along geodesics with respect to the leafwise metric g. For every x ∈

M \E, fix an arbitrary (locally) geodesic ωx : [0, ∞) → Lx which is parameterized

by their length with respect to g and which starts at x, i.e. ω(0) = x. Consider

the function fx : R+ × Nx (F ) \ {0} → R given by

fx (t, v) := log

kH(ωx , t)vk

,

kvk

t ∈ R+ , v ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0}.

The following lemmas give us optimal estimate on the transverse expansion rate

while traveling along g-geodesics.

15

Lemma 3.2. There exists a constant c > 1 independent of x ∈ M \ E and of the

choice of a geodesic ωx such that

log⋆ dist(ωx (t), E))

∂fx (t, v)

≤c

,

∂t

ξ(ωx (t))

t ∈ R+ , v ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0}.

Proof. It suffices to show that

log⋆ dist(x, E)

∂fx (t, v) ≤

c

,

∂t t=0

ξ(x)

v ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0},

(12)

for a constant c > 1 independent of x ∈ M \ E. Consider two cases.

Case 1: x is contained in a regular flow box Ui .

Using that the map fx (t, v) is smooth with respect to the variables (t, v) as

well as the parameter x and using that the compact set Ui does not meet E, we

can show that

∂fx (t, v) ≤ c,

v ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0},

∂t t=0

for a constant c > 1 independent of x. This, combined with the estimate dist(x, E) ≥

1/2 and ξ(x) ≥ c′ for x ∈ Ui , implies (12) in this case.

Case 2: x is contained in a singular flow box Ue .

2

Recall that g = ξ 2 gP and gM = η 2 gP , it follows that gM = ηξ2 g. Consequently,

using that ωx (0) = x, we obtain that

∂fx (t, v) kωx (t) − ωx (0)k

η(x)

=

lim

·

D

log

H(x,

·)v.

=

· D log H(x, ·)v.

∂t t=0 t→0

t

ξ(x)

Applying Lemma 2.1 and Lemma 3.1, the absolute value of the last expression is

is dominated by a constant times

kxk| log kxk| 1

| log kxk|

·

=

,

ξ(x)

kxk

ξ(x)

which proves the lemma.

Lemma 3.3. There is a constant c > 0 independent of x and ωx such that

log⋆ dist(x, E)et

∂fx (t, v)

≤c

,

∂t

ξ(x)

t ∈ R+ , v ∈ Nx (F ) \ {0}.

Proof. By Lemma 3.2 it suffices to show that

log⋆ dist(ωx (t), E)

log⋆ dist(x, E)et

≤c

,

ξ(ωx (t))

ξ(x)

t ∈ R+ .

(13)

Fix a t > 0. We divide [0, t] into a finite number of interval [tj , tj+1] with 0 ≤ j ≤

n − 1 such that t0 = 0, tn = t and that each [tj , tj+1 ] is contained in a (singular

16

or regular) flow box. By an induction argument on n, it is sufficient to show that

if (13) holds for tn−1 , then it also holds for t = tn . We consider two cases.

Case 1: x is contained in a regular flow box Ui .

Since ξ(y) ≥ c for all y ∈ M \ E for some constant c and y 7→ log⋆ dist(y, E)

and y 7→ ξ(y) are both bounded on Ui , it follows that

log⋆ dist(ωx (t), E)

≤ c and

ξ(ωx (t))

log⋆ dist(x, E)et

1

≥ ,

ξ(x)

c

proving (13) in this case.

Case 2: x is contained in a singular flow box Ue ≃ Dk \ {0}.

Suppose without loss of generality that ωx (tn−1 ) is contained in a (2D)k \ {0}.

In (13) we may replace log⋆ dist(ωx (τ ), E) by kωx (τ )k and ξ(ωx (τ )) by ρ(kωx (τ )k)

for all τ ∈ [tn−1 , tn ]. Consequently, (13) is reduced to

log kωx (tn−1 )ket

log kωx (τ )k

≤c

,

ρ(kωx (τ )k)

ρ(kωx (tn−1 )k)

τ ∈ [tn−1 , tn ].

Taking the logarithm of both members, the last estimate is equivalent to the

existence of c > 0 such that

d

log kωx (τ )k ≤ c,

τ ∈ [tn−1 , tn ].

dτ

ρ(kωx (τ )k) 2

2

Recall that gM = ηξ2 g ≈ ηρ2 g on leaves in Dk \ {0} and that η(x) ≈ −kxk log kxk

for x ∈ (1/2D)k \ {0} according to Lemma 2.1. Using this and making the change

of variable r := kωx (τ )k, the previous condition becomes

d

r

log

r

(log log r − log ρ(r)) ·

< c.

dr

ρ(r) 1

c

d

( ρ(r)

)| ≤ −r log

for all 0 < r < r0 with some

This is equivalent to the condition | dr

r

r0 > 0, which follows, in turn, from Definition 1.1 (iii-b) and the assumption that

g is accelerating. So (13) is proved in this last case.

4

Proof of the main result

In what follows we denote by distg the distance induced by the metric g on leaves

of the foliation (M, F , E). We need the following two preparatory results.

Lemma 4.1. There is a finite constant c0 > 0 such that for all x ∈ M \ E and

all s ≥ 1,

(

)

Wx

ω ∈ Ω : sup distg (ω(0), ω(t)) > s

t∈[0,1]

17

2

< c0 e−s .

Proof. Let φx : D → Lx be a universal covering map with φx (0) = x. We have to

show that

(

)

W0

ω ∈ Ω(D) : sup distϕ∗x g (ω(0), ω(t)) > s

< c0 e−s

2

t∈[0,1]

where W0 is the Wiener measure at 0 of the disc D endowed with the metric ϕ∗x g.

Since the metric g is accelerating, (D, ϕ∗x g) is complete and of uniformly bounded

geometry. Consequently, the last assertion follows by combining Lemma 8.16 and

Corollary 8.8 in [4].

Here is the second preparatory result.

Proposition 4.2. There are constants c1 , c2 > 0 such that

⋆

log kA±1(ω, t)k ≤ c1 log dist(ω(0), E) · ec2 distP (ω(t),ω(0)) ,

ω ∈ Ω, t ∈ R+ .

ξ(ω(0))

Proof. We only give the estimate for log kA(ω, t)k since the estimate for log kA−1 (ω, t)k

can be proved similarly. Let ω ∈ Ω and t ∈ R+ . Put x := ω(0) and y := ω(t).

Let ωx be a geodesic starting at x and passing through y such that the segment

of ωx delimited by x and y is homotopic with the curve ω|[0,t] on the leaf Lx . So

there is a unique s ∈ R+ such that ωx (s) = y. By Lemma 3.3, we have that

Z

Z s

log⋆ dist(x, E) s t

log⋆ dist(x, E) c2 s

∂fx (t, v)

dt ≤ c4

e dt = c4

e .

fx (s, v) =

∂t

ξ(x)

ξ(x)

0

0

Since distg (ω(t), ω(0)) = distg (x, y) = s, this completes the proof.

Now we arrive at the

End of the proof of the Main Theorem. By Proposition 4.2, we have that

⋆

log kA±1 (ω, t)k ≤ c1 log dist(ω(0), E) · ec2 distg (ω(t),ω(0)) ,

ξ(ω(0))

ω ∈ Ω, t ∈ R+ .

Therefore,

Z

Z

log⋆ dist(ω(0), E) c2 ·supt∈[0,1] distg (ω(0),ω(t))

e

dµ̄(ω).

F (ω)dµ̄(ω) ≤ c1

ξ(ω(0))

Ω

Ω

By formula (8) we may rewrite the integral on the right hand side as

Z

Z

log⋆ dist(x, E) c2 ·supt∈[0,1] distg (ω(0),ω(t))

e

dWx (ω) dµ(x).

·

ξ(x)

X

Ωx

(14)

Next, we will show that there is a constant c3 > 0 independent of x such that

the inner integral is uniformly bounded by c3 , that is,

Z

ec2 ·supt∈[0,1] distg (ω(0),ω(t)) dWx (ω) < c3 .

(15)

Ωx

18

To this end we focus on a single L passing through a given point x. Observe that

Z ∞

Z

c2 ·supt∈[0,1] distg (ω(0),ω(1))

e

dWx (ω) =

Wx {ω ∈ Ωx : ec2 ·supt∈[0,1] distg (ω(0),ω(t)) > s}ds.

0

Ωx

The integrand on the right-hand side is equal to

Wx {ω ∈ Ωx : sup distg (ω(0), ω(t)) > log s/c2 }.

t∈[0,1]

For 0 ≤ s ≤ ec2 , this quantity is clearly ≤ 1. For s ≥R ec2 , this quantity is

2 2

2 2

∞

dominated, thanks to Lemma 4.1, by c0 e−(log s) /c2 . Since ec2 e−(log s) /c2 ds < ∞,

we deduce that

Z

ec2 ·distg (ω(0),ω(t)) dWx (ω)

Ωx

is bounded from above by a constant independent of x. This proves (15).

Using (15) the integral in (14) is dominated by a constant times

Z

log⋆ dist(x, E)

dµ(x).

ξ(x)

X

⋆

is locally bounded. Therefore,

Observe that the function x ∋ M \E 7→ log dist(x,E)

ξ(x)

in order to show that the last integral is finite, it is sufficient to show that it is

finite in a singular flow box Ue ≃ (2D)k \ {0}. Note that the metric gM coincides

2

2

with the standard Kähler metric i∂∂kzk2 in (2D)k . Recall that gM = ηξ2 g ≈ ηρ2 g

on leaves in Dk \{0} and that η(x) ≈ −kxk log kxk for x ∈ (1/2D)k \{0} according

to Lemma 2.1. Let T be a positive ∂∂-closed current on Dk such that µ = T ∧ g.

We only have to show that the integral on the the ball B1/2 , with respect to the

2

measure T ∧ i∂∂kzk

, of the radial function γ(r) := r −2 | log r|−1 ρ(r)−2 is finite.

R

Let m(r) := Br T ∧ i∂∂kzk2 . Since the Lelong number of T at 0 exists and is

finite, we have m(r) . r 2 (see Lemma 2.4 in [11]). Using an integration by parts,

the considered integral is equal, up to finite constants, to

Z 1

Z 1

1

2 ′

−

r e

γ (r)dr = −2

rγ(r)dr − −r 2 γ(r) 0 .

0

0

Since g is accelerating, it follows from the second integrability condition in Definition 1.1 (iii-c) that the integral on the right hand side is finite. By Definition 1.1

(iii-b) the last term on the right hand side is also finite. Hence, F is µ̄-integrable.

Remark 4.3. Now let g = gP , that is, ξ ≡ 1. For each gP -harmonic probability

measure µ let T be a positive ∂∂-closed current on M such that µ = T ∧ gP . Fix a

singular flow box Ue of a singular point e ∈ E, and identifies (Ue , e) with (Dk , 0).

Suppose that the numbers λ1 , . . . , λk ∈ C \ {0} are “generic”, for example, they

19

are pairwise non R-linear. Suppose also that the Lelong number of T at 0 is > 0.

The last assumption seems reasonable since it is usually expected that the mass

of T concentrates near E. We will show that

Z

log kA(ω, 1)kdµ̄(ω) = ∞.

(16)

Ω

This is an evidence showing that an acceleration of the Poincaré metric is possibly

unavoidable. Indeed, let D be endowed with the Poincaré metric gP , and consider

the following subspace of Ω0 (D) :

A := {ω ∈ Ω0 (D) : 1 < distgP (0, ω(1)) < 2} .

By (5) and (6), W0 (A) > 0. Since λ1 , . . . , λk are generic, we argue as in Section

3 for ξ ≡ 1. Therefore, we can show that there is 0 < c < 1 such that

log kA(ω, 1)k ≈ − log kxk

for each 0 < kxk < c and ω ∈ φx ◦ A. Consequently, the integral in (16) is greater

than a positive constant times W0 (A) > 0 times

Z

− log kxkdµ(x).

0<kxk<c

Since the Lelong number of T at 0 is > 0, we get that m(r) ≈ r 2 . Hence, arguing

as the end of the proof of the Main Theorem, the last integral is

Z c

dr

= ∞.

−

0 r log r

This proves (16).

5

Lyapunov exponents and Oseledec decomposition

Let (M, F , E) be a foliation in a Hermitian complex manifold (M, gM ) of dimension k. Recall from the definition of the holonomy cocycle that given any path

ω ∈ Ω and any time t ≥ 0, H(ω, t) is a C-linear isomorphism from Nω(0) (F ) onto

Nω(t) (F ). In the literature there are several versions of a Lyapunov exponent

of H. The most geometric way is to characterize the Lyapunov exponent as the

maximal transverse expansion rate along geodesics (see, for example, Hurder’s

survey article [20] for a systematic exposition). On the other hand, in the case

where dim(M) = 2 and E = ∅, Candel and Deroin [4, 10] define the (unique)

Lyapunov exponent of H as the transverse expansion rate along a leawise Brownian path. We generalize the last authors’ approach to the higher dimension.

Note, moreover, that in the next work [24] we will give geometric interpretations

of our Lyapunov exponents.

20

Definition 5.1. The transverse expansion rate along a path ω ∈ Ω in the direction v ∈ Nω(0) (F ) \ {0} at time t > 0 is

E (ω, t, v) :=

1

kH(ω, t)vk

log

.

t

kvk

The transverse expansion rate along a path ω ∈ Ω at time t > 0 is

E (ω, t) :=

1

log kH(ω, t)k =

sup

E (ω, t, v).

t

v∈Nω(0) (F )\{0}

Here k · k denotes the gM -norm. The angle between two complex (resp. real)

subspaces V, W of Nx (F ) for each point x ∈ M \ E, is, by definition,

∡ V, W := min {arccoshv, wi : v ∈ V, w ∈ W, kvk = kwk = 1} ,

where h·, ·i is the gM -Hermitian inner product.

Theorem 5.2. We keep the hypotheses of Main Theorem. Assume in addition

that the g-harmonic probability measure µ is ergodic. Then there exists a leafwise

saturated Borel subset X of M with µ(X) = 1 and a number m ∈ N and m

integers d1 , . . . , dm ∈ N such that the following properties hold:

(i) For each x ∈ X there exists a decomposition of Nx (F ) as a direct sum of

complex linear subspaces

Nx (F ) = ⊕m

i=1 Hi (x),

such that dim Hi (x) = di and that the following holonomy invariant property

holds: H(ω, t)Hi (x) = Hi (ω(t)) for all ω ∈ Ωx and t ∈ R+ . Moreover, x 7→ Hi (x)

is a measurable map from X into the Grassmannian of Nx (F ). Moreover, there

are real numbers

χm < χm−1 < · · · < χ2 < χ1

such that

lim E (ω, t, v) = χi ,

t→∞

uniformly on v ∈ Hi (x) \ {0}, for Wx -almost every ω ∈ Ωx . The numbers χm <

χm−1 < · · · < χ2 < χ1 are called the Lyapunov exponents of the foliation.

(ii) The maximal Lyapunov exponent χ1 may be characterized by the following

formula:

χ1 = lim E (ω, t)

t→∞

for Wx -almost every ω ∈ Ωx and for every x ∈ X.

(iii) For S ⊂ N := {1, . . . , m} let HS (x) := ⊕i∈S Hi (x). Then

1

log sin ∡ HS (ω(t)), HN \S (ω(t)) = 0

t→∞ t

lim

for Wx -almost every ω ∈ Ωx .

21

Some remarks are in order.

m(x)

• The decomposition of Nx (F ) as a direct sum of complex subspaces ⊕i=1 Hi (x),

given in (i) is said to be the Oseledec decomposition at a point x ∈ Y.

• Following assertion (ii) the Lyapunov exponents measures, in some sense,

the growth rate of the derivative of the holonomy map along a generic Brownian leafwise path. Theorem 5.2 gives us a full characterization of of Lyapunov

exponents of a foliation. When k > 2, there are, in general, several Lyapunov

exponents.

Observe that both the source space and the target space of the C-linear invertible transformation H(ω, t) may vary as ω|[0,t] varies. In order to apply our

previous work [23], we need to work with a conjugate A of H such that all isomorphisms A(ω, t) have Ck−1 as their source spaces and target spaces, namely,

A(ω, t) ∈ GL(k − 1, C). This consideration leads us to the following notion.

An identifier τ is a suitable smooth map which associates to each point x ∈

M \ E a C-linear isometry τ (x) : Nx (F ) → Ck−1 , that is, τ (x) is a C-linear

morphism such that

kτ (x)vk = kvk,

v ∈ Nx (F ), x ∈ M \ E.

(17)

Here we have used the Euclidean norm in Ck−1 on the left-hand side and the

induced gM -norm on the right hand side. We identify every fiber Nx (F ) with

Ck−1 via τ. Using a partition of unity of M, we can show that there always exists

an identifier. The holonomy cocycle A of (M, F , E) with respect to the identifier

τ is defined by

A(ω, t) := τ (ω(t)) ◦ H(ω, t) ◦ τ −1 (ω(0)),

ω ∈ Ω, t ∈ R+ .

(18)

By Proposition 3.3 in [23], A is a (multiplicative) cocycle in the sense of this cited

work. We deduce from the above discussion the following relation between the

transverse expansion rate functions given in Definition 5.1 and the cocycle A :

1

kA(ω, t)(τ (ω(0))v)k

log

,

t

kτ (ω(0))vk

(19)

1

E (ω, t) = log kA(ω, t)(τ (ω(0))v)k.

t

for every path ω ∈ Ω and v ∈ Nω(0) (F ), v 6= 0, and time t > 0.

End of the proof of Theorem 5.2. Using equalities (17) and (18) the integrability of F given by the the Main Theorem implies that the function

E (ω, t, v) =

Ω ∋ ω 7→ sup max{| log kA(ω, t)k|, | log kA−1 (ω, t)k|}

t∈[0,1]

is µ̄-integrable. Therefore, we are in the position to apply Corollary 3.6 in [23].

Consequently, we obtain the characterization of Lyapunov exponents as well as

the corresponding Oseledec decomposition of the cocycle A. This, combined with

the two identities in (19) and equalities (17)-(18) implies the desired conclusions

of the theorem.

22

References

[1] Berndtsson, Bo; Sibony, Nessim. The ∂-equation on a positive current. Invent.

Math. 147 (2002), no. 2, 371-428.

[2] Brunella, Marco. Inexistence of invariant measures for generic rational differential

equations in the complex domain, Bol. Soc. Mat. Mexicana (3), 12 (2006), no. 1,

4349.

[3] Candel, Alberto. Uniformization of surface laminations, Ann. Sci. École Norm.

Sup. (4), 26 (1993), no. 4, 489-516.

[4] —–. The harmonic measures of Lucy Garnett, Adv. Math., 176 (2003), no. 2,

187-247.

[5] Candel, Alberto; Conlon, Lawrence. Foliations. I. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 23. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI, 2000. xiv+402 pp.

[6] —–. Foliations. II. Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 60. American Mathematical

Society, Providence, RI, 2003. xiv+545 pp.

[7] Candel, A.; Gómez-Mont, X. Uniformization of the leaves of a rational vector field.

Ann. Inst. Fourier (Grenoble), 45 (1995), no. 4, 1123-1133.

[8] Chavel, Isaac. Eigenvalues in Riemannian geometry. Including a chapter by Burton

Randol. With an appendix by Jozef Dodziuk. Pure and Applied Mathematics, 115.

Academic Press, Inc., Orlando, FL, 1984. xiv+362 pp.

[9] Cheeger, Jeff; Gromov, Mikhail; Taylor, Michael. Finite propagation speed, kernel

estimates for functions of the Laplace operator, and the geometry of complete

Riemannian manifolds. J. Differential Geom. 17 (1982), no. 1, 15-53.

[10] Deroin, Bertrand. Hypersurfaces Levi-plates immergées dans les surfaces complexes de courbure positive. (French) [Immersed Levi-flat hypersurfaces in complex surfaces of positive curvature]. Ann. Sci. École Norm. Sup. (4) 38 (2005),

no. 1, 57-75.

[11] Dinh, T.-C.; Nguyên, V.-A.; Sibony, N. Heat equation and ergodic theorems for

Riemann surface laminations. Math. Ann. 354, (2012), no. 1, 331-376.

[12] —–. Entropy for hyperbolic Riemann surface laminations I. Frontiers in Complex

Dynamics: a volume in honor of John Milnor’s 80th birthday, (A. Bonifant, M.

Lyubich, S. Sutherland, editors), (2012), Princeton University Press, 24 pages.

[13] —–. Entropy for hyperbolic Riemann surface laminations II. Frontiers in Complex

Dynamics: a volume in honor of John Milnor’s 80th birthday, (A. Bonifant, M.

Lyubich, S. Sutherland, editors), (2012), Princeton University Press, 29 pages.

[14] Fornæss, J.-E.; Sibony, N. Harmonic currents of finite energy and laminations.

Geom. Funct. Anal., 15 (2005), no. 5, 962-1003.

23

[15] —–. Riemann surface laminations with singularities. J. Geom. Anal., 18 (2008),

no. 2, 400-442.

[16] —–. Unique ergodicity of harmonic currents on singular foliations of P2 . Geom.

Funct. Anal., 19 (2010), no. 5, 1334-1377.

[17] Garnett, Lucy. Foliations, the ergodic theorem and Brownian motion. J. Funct.

Anal. 51 (1983), no. 3, 285-311.

[18] Glutsyuk, A.A. Hyperbolicity of the leaves of a generic one-dimensional holomorphic foliation on a nonsingular projective algebraic variety. (Russian) Tr. Mat.

Inst. Steklova, 213 (1997), Differ. Uravn. s Veshchestv. i Kompleks. Vrem., 90111; translation in Proc. Steklov Inst. Math. 1996, no. 2, 213, 83-103.

[19] Ghys, Étienne. Laminations par surfaces de Riemann. (French) [Laminations by

Riemann surfaces] Dynamique et géométrie complexes (Lyon, 1997), ix, xi, 49-95,

Panor. Synthèses, 8, Soc. Math. France, Paris, 1999.

[20] Hurder, Steven. Classifying foliations. Foliations, geometry, and topology, 1-65,

Contemp. Math., 498, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, 2009.

[21] Katok, Anatole; Hasselblatt, Boris. Introduction to the modern theory of dynamical systems. With a supplementary chapter by Katok and Leonardo Mendoza. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 54. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, 1995. xviii+802 pp.

[22] Lins Neto A. Uniformization and the Poincaré metric on the leaves of a foliation

by curves. Bol. Soc. Brasil. Mat. (N.S.), 31 (2000), no. 3, 351-366.

[23] Nguyên, V.-A. Oseledec multiplicative ergodic theorem for laminations.

ArXiv:1403., 146 pages.

[24] Nguyên, V.-A. Geometric characterization of Lyapunov exponents for Riemann

surface foliations. in preparation.

[25] Lins Neto, A.; Soares M. G. Algebraic solutions of one-dimensional foliations. J.

Differential Geom., 43 (1996), no. 3, 652-673.

[26] Oseledec, V.-I. A multiplicative ergodic theorem. Lyapunov characteristic numbers

for dynamical systems. Trans. Moscow Math. Soc., 19 (1968), 197-221.

[27] Pesin, Ja. B. Characteristic Lyapunov exponents and smooth ergodic theory. Russian Math. Surveys, 32, (1977), 55-114.

[28] Sullivan, Dennis. Cycles for the dynamical study of foliated manifolds and complex

manifolds. Invent. Math. 36 (1976), 225-255.

[29] Walczak, Pawel. Dynamics of foliations, groups and pseudogroups. Instytut

Matematyczny Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Monografie Matematyczne (New Series)

[Mathematics Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences. Mathematical Monographs (New Series)], 64. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2004. xii+225 pp.

24

Viêt-Anh Nguyên, Mathématique-Bâtiment 425, UMR 8628, Université Paris-Sud,

91405 Orsay, France.

VietAnh.Nguyen@math.u-psud.fr, http://www.math.u-psud.fr/∼vietanh

25