View/Open - ETD Repository Home

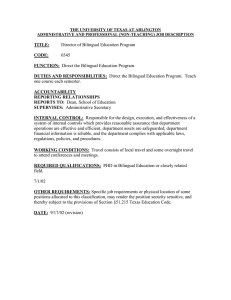

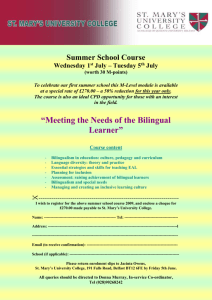

advertisement