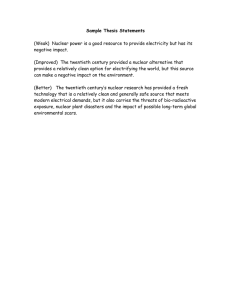

USA - OECD Nuclear Energy Agency

advertisement