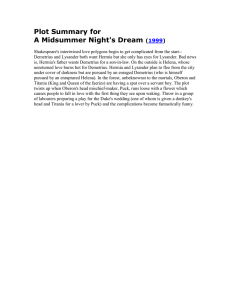

A Midsummer Night`s Dream

advertisement