Reclaiming End-of-Life Cathode Ray Tubes (CRTs), and Electronics

advertisement

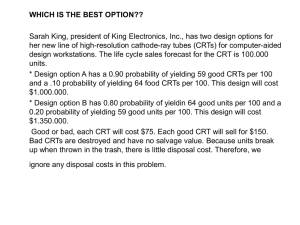

Reclaiming End-of-Life Cathode Ray Tubes (CRTs), and Electronics: A Florida Update John L. (Jack) Price Hazardous Waste Management Section Florida Department of Environmental Protection Tallahassee, Florida ABSTRACT The disposition of end-of-life CRTs, computers and other electronic equipment is an emerging environmental issue on which Florida, like Massachusetts and a few other states, has taken action. Florida has focused upon CRTs as the most problematic material in the electronics waste stream due to their lead content. CRTs are the second largest source of lead in Florida’s municipal solid waste stream just behind lead acid batteries. Like Massachusetts, Florida’s strategy includes regulatory streamlining, electronics recycling infrastructure development, time-limited state funding and possibly disposal restrictions to encourage the recycling of end-of-life electronics and especially CRTs. The major difference between Florida’s and Massachusetts’ strategies is the regulatory interpretation. Florida’s interpretation may be a better fit for some states since U.S. EPA Region IV has given preliminary approval to its interpretation of how RCRA applies to CRT management while U.S. EPA Region I has not accepted the Massachusetts approach of exempting unbroken CRTs from RCRA by rule. The lessons learned from both Florida’s and Massachusetts’ strategies and programs for managing end-of-life electronics can be helpful as other states begin to deal with this emerging environmental issue. BACKGROUND Electronic equipment, especially computers and televisions, are a ubiquitous part of life, with per capita ownership expected to rise for the foreseeable future. Equipment obsolescence due to technological advances such as increasing computer speed and memory, high definition television and flat panel computer monitors will likely increase discards of these items. Recent estimates suggest that in 1999, 160,000 computers will be discarded into Florida landfills with 410,000 being recycled and 1,410,000 in storage for eventual discard (Matthews, 1997, factored for Florida’s population). By 2005, these numbers could increase to 420,000 landfilled, 1,100,000 recycled, and 3,800,000 stored. The more recent EPR2 Baseline Report suggests that these estimates may be 30-40% low (National Safety Council, 1999). Similarly, television discards into Florida landfills may increase from 1,040,000 in 1999 to 1,200,00 in 2005 (Lowry, 1998, factored for Florida’s population; assumes no recycling). While much older equipment will be reused or stored for an additional 3-6 years after its 5 year average estimated initial useful life, all electronic equipment will sooner or later be discarded. This equipment represents a significant volume of waste material, but the primary concern is with heavy metal content, particularly lead from cathode ray tubes (CRTs). The current regulatory interpretation surrounding the management of this discarded equipment is hampering the development of a reuse and recycling infrastructure. The CRT part of this discarded electronics waste stream appears to be the most problematic at this time and hence is the focus of Florida’s strategy. CRTs in the form of computer monitors and TVs account for ~80% of the items received in electronics collections and are more expensive to recycle than other computer and electronics equipment. Computers, computer peripherals (key boards, printers) and other end-of-life electronics (VCRs, radios, tape players, etc.) commonly utilize collection routes and demanufacturing/recycling facilities at end-of-life which are similar or identical to CRTs, but these non-CRT materials are not normally subject to the hazardous waste regulations which apply to CRTs. If regulatory impediments to CRT end-of-life management are reduced or removed and the recycling infrastructure is encouraged by increased volumes, the flow and recycling of all end-of-life electronics will be enhanced. CRT recycling rates are very low (Figures 1 and 2) due in large part to the existing regulatory status of CRTs, the confusion surrounding this status and the attendant high costs of recycling. The recycling rate for TVs varies from 0.7 -0.11%. For example, in Florida in 1999 it is estimated that of the 1.3 million TVs becoming obsolete (potentially discarded), only about 1,000 were recycled. These projected discards may increase dramatically depending on the speed with which High Definition TV and flat panel TV displace our current sets. The recycling rate for computer monitors varies from 9.4 15.7%. For example, in 1999 it is estimated that of the 941,000 monitors becoming obsolete (potentially discarded), only about 88,000 were recycled. The balance of these monitors were either landfilled, incinerated or stored. It is thought that the vast majority of these non recycled monitors are in storage because their owners think they still have value. This “storage so that I can sell it for a lot later” thinking over the past few years has accumulated a large quantity of monitors, perhaps 1.5 million or more, currently in storage just waiting to descend on Florida’s local solid waste managers. The Florida DEP wants to be ready for this avalanche should it materialize as a slug or be intensified by a wave of discards due to fear of the Y2K problem or the advent of flat panel monitors. We need to get the lead out of our efforts to get the lead out of the waste stream from CRTs used in computer monitors and TVs. Florida’s approach to this problem will be compared to Massachusett’s approach to illustrate two slightly different ways to approach the regulatory and programmatic aspects of end-of-life CRT management with the same goal: increase recycling and decrease lead from these products in landfilled or incinerated MSW. In addition, Florida’s strategy for end-of-life electronics, especially CRTs, will be presented in detail. T Vs in Florid a In Thousands 2,000 1,500 O bsolete 1,000 R ecycled 500 0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Figure 1: Projections of obsolete and recycled TVs in Florida 1999-2003. [Source: National Safety Council, 1999.] In Thousands Com pute r M onitors in Florida 1,600 1,400 1,200 1,000 800 600 400 200 0 1999 Obs olete Rec y c led 2000 2001 2002 2003 Figure 2: Projections of obsolete and recycled computer monitors in Florida 1999-2003. . [Source: National Safety Council, 1999.] What’s in a CRT? A CRT in a TV or a computer monitor can contain from ~1.5 to nearly 6 pounds of lead, depending on the size and year of manufacture (4 pounds per CRT is sometimes used as a rough average). The CRT glass can be divided into 4 parts which have differing amounts of lead in different chemical and physical forms: 1. Neck: The neck glass houses the electron gun (source of the signal leading to the display we see when we look at the TV or monitor). 2. Funnel: Lead is bound up in the glass matrix of the funnel (22-25% lead) as “leaded glass” for shielding us from the radiation produced by the gun. 3. Faceplate or panel: A minimal amount of lead (~2-3%) bound up in the glass matrix. The function of the lead is not known. 4. Frit: Frit is a type of glass solder used to join the faceplate and funnel sections. It contains from ~15 to nearly 100 grams of lead per CRT, depending on the size. The lead from the frit is in a soluble form, primarily lead oxide, as compared to the insoluble lead in the glass matrix of the funnel and faceplate. The lead in the frit readily leaches in both the US EPA’s TCLP (Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure) hazardous waste characterization test and in the landfill or environment. To a lesser extent, lead may also leach from the funnel or panel glass depending on the particle size of the broken glass. The concern with CRTs is the fate of the lead upon disposal into the municipal solid waste (MSW) stream. More than 40% of the lead discarded into Florida’s MSW in 2000 is estimated to come from CRTs in computer monitors and TVs (Figure 3). The DEP’s stated goal in its 1995 Agency Strategic Plan is to reduce the amount of lead in Florida’s MSW by at least 50% by 2000 based upon the 1995 levels. It is critical that the DEP take any and all effective steps to increase the reuse or recycling of CRTs in order to meet its lead reduction goal. Vehicular lead acid (VLA) batteries are the leading source of lead in Florida’s MSW despite a national recycling rate that has been above 95% since the late 1980’s. But, due to the large amount of lead per battery (~19 pounds) and the large number of these batteries in use, even the 5% of these batteries which are not recycled are still the largest contributor of lead to Florida MSW. The DEP is exploring ways to further reduce this source of lead. Small sealed lead acid (SSLA) batteries are another source of lead. As compared to VLA batteries which have a liquid electrolyte, SSLA battery electrolyte is in a gelled form or held in a more-or-less solid matrix of fibers, thus not free to spill out. This also allows the battery to be sealed rather than open (via removable caps) as VLA batteries are. The DEP has been working with the Portable Rechargeable Battery Association (PRBA) to encourage an industry wide collection program for these batteries. Other minor sources of lead in Florida’s MSW include glass and ceramics (leaded glass, ceramic glazes) , plastics (stabilizers ), circuit boards (solder), leaded wine bottle foils and miscellaneous items. Sources of Pb in FL MSW, 2000 (Est.) Computer Monitors 1,033 TV Tubes 1,768 Other 779 VLA Batteries 2,586 SSLA Batteries 572 Total 6,739 Tons Figure 3: Estimated sources of lead in Florida’s municipal solid waste. [Source: Florida Department of Environmental Protection estimate.] FLORIDA AND MASSACHUSETTS: TWO APPROACHES, SAME GOAL Regulatory Status Both states recognize the obvious need to remove the existing RCRA regulatory barriers that impede the movement of end-of-life CRTs to recycling or proper disposal. Figure 4 depicts many of the possible routes that end-of-life CRTs can follow from discard for recycling by households or businesses through transporters, handlers, demanufacturers and finally to the CRT specialist. Even a quick look at this chart tells us that full RCRA hazardous waste regulations would hopelessly snarl an already complicated transportation, handling and recycling network. The current abysmal recycling rates for CRTs bear this out. Florida and Massachusetts have the same goal to encourage recycling and decrease the amount of lead and other materials that are landfilled or incinerated, but the selected regulatory framework is different. While Massachusetts has declared by state rule (310 CMR 30.000) that unbroken CRTs are not Figure 4: End-of-life CRT management infrastructure for demanufacturing and recycling. (Based on Robin Ingenthron, MA DEP, presentation at 1999Electronic Product Recovery and Recycling Conference, March 23, 1999, Arlington, VA.) hazardous wastes, Florida emphasizes that CRTs are and will remain hazardous wastes under RCRA when discarded in regulated quantities to landfills or municipal waste combustors. However, under Florida’s interpretation of RCRA, 40 CFR 261.2(e)(ii), CRTs are neither hazardous nor solid wastes when reused as a substitute for commercial products, i.e., glass for new CRTs or a fluxing agent in a secondary lead smelter. Florida’s approach seems to be more palatable to US EPA. While continuing discussions on CRT regulation with Massachusetts, EPA Region I has rejected Massachusetts’ deregulation rule because it “is not equivalent to, and is less stringent than” RCRA (64 FR 9110, February 24, 1999). In contrast, Region IV has given tacit approval for Florida to move forward with its interpretation. Florida is using this interpretation in its pilot end-of-life CRT management project being done at a Florida secondary lead smelter under RCRA’s treatability study provisions at 40 CFR 261.4(e) and (f). Upon successful completion of the treatability study, Florida will ask EPA Region IV to formally accept this interpretation of RCRA with respect to CRT management. Note that EPA has already issued regulations exempting from RCRA reuse as glass for new CRTs as recommended by its Common Sense Initiative Committee on Computers and Electronics. To clarify how and where Florida’s regulatory interpretation applies to end-of-life CRTs, it is helpful to distinguish between what happens before and after the CRT reaches the CRT specialist (Figure 4). The CRT specialist may also be a demanufacturer but is depicted as a separate block here for clarity. Until an unbroken CRT reaches the CRT specialist, it is still a “product” in that it is either functioning or can be repaired to a functioning state and offered for resale. Given the complexity of the routes which CRTs may travel on the way to the CRT specialist, regulation of the CRT as a hazardous waste between the households or businesses and the CRT specialist would significantly inhibit their movement to beneficial reuse or proper disposal. If businesses were to discard their CRTs instead of sending them to a CRT specialist, they would be subject to full hazardous waste regulations. If discarded in regulated quantities, the CRTs would need to be transported to a hazardous waste landfill by a licensed hazardous waste transporter with all the associated manifesting, record keeping and reporting. The CRT specialist makes the determination whether to repair the CRT based upon cost and demand for resale. Thus, the CRT specialist becomes the “generator” of the waste CRT. If not repaired, the CRT will either be recycled (into new CRTs or used as a fluxing agent in a secondary lead smelter) or disposed. The CRT specialist is the facility that determines that a CRT will not be repaired. All CRTs that are not physically broken can be repaired: the question is the cost effectiveness of repairing the CRT. Listed from most to least desirable from an environmental perspective, the four options available for the CRT specialist are resale, use to make new CRTs, use as a fluxing agent in a secondary lead smelter, and disposal. Of the four options available for the CRT specialist, only disposal would trigger management as hazardous wastes under Florida’s regulatory strategy. There are domestic and foreign resale markets for both computer monitors and TVs, even black and white TVs. The extent and location of these markets are not well known as they are closely guarded commercial information of critical competitive value to TV and computer repair companies. For the CRT glass to be reused for manufacture of new CRTs, the face glass must be separated from the neck and funnel glass and lead frit bonding compound. This separation is due to the differing lead contents of face v. neck/funnel glass (much less lead in face glass). This separation is currently done by sawing the CRT just forward of the lead frit bonding compound. One Florida electronics demanufacturer currently does such sawing. For CRT glass to be reused as a fluxing agent in a secondary lead smelter (recycler of vehicular lead acid batteries), there is no need to separate the two types of glass. The glass functions as a fluxing agent in the lead smelter. Secondarily, most of the lead in the glass is recovered as well. Infrastructure Development Florida and Massachusetts are taking similar steps to build the collection and recycling infrastructure for electronics and CRT recycling. These steps include financial assistance to local governments, state grant funding and a statewide recycling contract. The goal is to push more electronics through the existing recycling infrastructure and “grow” it to the point that economies of scale will drive down the costs of recycling CRTs. Currently, the component and scrap value of computers and telecommunications equipment make their recycling reasonably attractive and in some cases even result in a positive value to the generator, i.e., the recycler pays for the unwanted equipment. CRTs have a negative value, i.e., cost, to the generator of ~$9 (monitors, small TVs) to ~$35 (console TVs). FL’s intent is to provide time limited funding to encourage local government programs until the cost of recycling decreases and local funding of such programs can be established. The state contract should eliminate the need for local governments to bid their own contracts as well as establish a lowest cost benchmark. The benchmark can also be used by private business generators as they negotiate contracts with electronics recyclers: “If you charge $5 under the state contract, why can’t you give me the same deal?” Florida is providing grants to Florida-based lead material recyclers to develop a local destination for CRTs that are recycled in lead smelters. Florida has one secondary lead smelter located in the state. Transportation costs are a large component of the CRT recycling cost. The use of a Florida smelter would cut transportation costs since almost all Florida CRTs currently being recycled in lead smelters are shipped out of state, commonly as far as Missouri. In its 1999 session the Florida Legislature passed SB 1434 and its House companion authorizing the appropriation of $400,000 in grants annually through FY 2004/2005 (5 years = $2 million total). According to Section 1 of SB 1434, the funds can be used for research and development; innovative technologies and equipment; and establishing a collection and transportation infrastructure for “the reuse, recycling and proper management of lead-containing materials” including CRTs. Florida’s grant priorities for Year 1 (FY 1999/2000) are $300,000 for innovative CRT recyclng technologies and equipment. This money will go “to FL based businesses that recycle lead-acid batteries and other lead-containing materials, including products such as televisions and computer monitors that utilize lead-containing cathode ray tubes” as specified in Section 2 of SB 1434. The remaining $100,000 will be used for collection infrastructure development. Other funding, especially for county programs, will be provided from Florida’s Household Hazardous Waste Collection Center Unique and Innovative Grant and its Recycling and Education Grant. A variety of pilot public and private management options and collection scenarios, described below, will be evaluated. 1. Local/State Agency Pilot: The DEP was directed in SB 1434, Section 3, to “implement a pilot program to collect lead-containing products, including end-of-life computers and other electronics from state and local agencies.” The DEP has begun discussions with various state agencies about such a pilot. 2. Municipal Collections: The DEP funded the ongoing dropoff program in Pasco County and a targeted collection program in Alachua County during FY 1998/1999. Pinellas County will likely collect at their HHW centers during FY 1999/2000. Another municipal collection strategy which should be tried is an ongoing curbside collection program. 3 TV Repair Shops: Since televisions tend to be the most common item received at both ongoing and targeted collections, it is apparent that TV repair shops play a vital role in endof-life TV management. To date, the DEP has been unable to make contact with this business sector as a group. The MA DEP has found out that TV repair shops have their own aftermarkets for repaired and discarded TVs which are relatively unknown to the Florida DEP and which tend to be different from the aftermarkets of computer repair shops (of which much more is known by the DEP). Recently, the DEP has found a trade group in Florida which represents electronics repair businesses. Investigation of this management route ought to be a priority for the DEP and its public and private partners. The Southern Waste Information Exchange (SWIX) targeted study, funded by the legislature, will be directed towards the TV repair industry. 4 Computer Repair Shops: These businesses and nonprofits repair computers for resale and remove operational and valuable components (e.g., memory, chips, drives) for resale at the highest level of reuse. These operations require at least some highly skilled staff who know what to fix (and how to fix it), what to keep and what to scrap. The DEP knows of at least two vocational school programs that teach computer repair and operations using discarded computers. Recently, it appears that the City of Tampa and the Hillsborough Education Foundation may be gearing up for a similar program. Large quantities of unrepairable or unusable (e.g., 286’s) computers, maybe as many as 2 for every 3 received, are generated by these operations. The unrepairable or unusable computers may proceed to electronics demanufacturers. It is important that these operations, especially the nonprofits, realize that they will have a significant waste stream to deal with. 5. Electronics Demanufacturers: These businesses demanufacture electronics for reusable and operational components and for scrap value. They landfill the rest (usually a very small fraction of the material stream). They may also test and repair computers (but rarely other electronics) for resale. Demanufacturing operations seem to be very attractive to nonprofit organizations since many of the tasks can be done by unskilled or semiskilled labor such as prisoners, former welfare recipients, or mentally disabled individuals. Training for these tasks is usually straightforward. The DEP has been working with Florida based electronics demanufacturers and gathering information from U.S. based operations at national conferences for over two years. As a consequence, the DEP has a good working knowledge of what actions are needed to encourage this part of the infrastructure, i.e., regulatory relief and increased throughput to bring down costs. The DEP believes that the necessary demanufacturing infrastructure currently exists in Florida. The three existing demanufacturers can easily open “satellite” operations which could service the entire state as the demand for service warrants. 6. Computer Leasing Businesses: These businesses lease computers to users for a fixed period of time after which the computer is returned. If the returned computer is obsolete, it may enter the used sale/export market or proceed to electronics demanufacturers or be discarded. The DEP has just begun to investigate how leasing operations fit into end-of-life computer management. Computer leasing will likely become more popular as the life spans of succeeding generations of computers shortens and business computer users, especially, wish to avoid or minimize end-of-life management costs or storage of obsolete equipment. 7. Thrift Shops/Charities - Used Goods: Thrift shops and other charities such as Goodwill and the Salvation Army often receive usable computers, TVs and other electronics as donations. However, much of the received equipment is either obsolete or inoperable and must proceed to demanufacturing and recycling or disposal. These locations may be able to serve as collection points for end-of-life electronics as well. 8. Moving Companies: There may be a significant electronics waste stream, especially TVs, from people who are moving out of the area. It is not known how much or what types of electronics tend to be left behind during a move but large, console TVs seem to be a likely candidate. Movers may be able to serve as collection points by directing “left behind” electronics to the appropriate point of the demanufacturing and recycling infrastructure. 9. Private Asset Recovery Operations: These companies specialize in providing the highest dollar return on discarded computer equipment from usually large scale business information system users such as banks and Fortune 500 type companies. These companies may also be electronics demanufacturers (e.g., SEER based in Tampa; Creative Recycling Systems based in Brandon) or may be a cost center for a MSW management company (e.g., Waste Management Asset Recovery Group). The DEP may be able to establish a public/private partnership with, for example, Waste Management Asset Recovery Group and an electronics manufacturer, such as Sony. The MN Office of Environmental Assistance (compliance assistance sister office of the MN Pollution Control Agency) has conducted a pilot with Waste Management and Sony during 1999. One consideration in such a pilot is that the private partners may want to direct the recovered assets to their own outlets as opposed to using Florida based electronics demanufacturers. Disposal Restrictions Both Florida and Massachusetts believe that any disposal restrictions or ban should be preceded by the development of a cost effective alternative to disposal, i.e., recycling at a reasonable cost. To that end, both states are adjusting the regulatory status, providing timelimited infrastructure funding and developing a state-wide contract for recycling of CRTs and other end-of-life electronics. Massachusetts has proposed a disposal ban for CRTs effective at a date certain as part of its CRT strategy. The date upon which this disposal ban is to become effective has been rescheduled to account for changes in the rate at which the infrastructure has developed to provide such a reasonable alternative to disposal. Florida recognizes that a disposal ban on regulated quantities of CRTs is currently in effect. Businesses that are Small Quantity or Large Quantity Generators under RCRA and that discard CRTs must manage those CRTs as hazardous wastes. In Florida, that means that these CRTs cannot be disposed in municipal solid waste landfills or municipal waste combustors. Florida will consider a disposal ban on CRTs from non-regulated businesses (including Conditionally Exempt Small Quantity Generators) and perhaps residential users at some future time as the infrastructure is deemed “adequate” and the recycling costs are deemed “reasonable.” While disposal bans in Florida have been effective, i.e., yard trash, white goods and tires, the imposition of such bans is not considered lightly. The Florida DEP would rather encourage proper management by all means possible prior to, or at least in conjunction with, a disposal ban. Whether Florida will impose disposal restrictions on non-regulated businesses and residential users is an open question at this time. CONCLUSION The disposition of end-of-life CRTs, computers and other electronic equipment is an emerging environmental issue on which Florida, like Massachusetts and a few other states, has taken action. Florida’s strategy is summarized in Appendix I. Florida has focused upon CRTs as the most problematic material in the electronics waste stream due to their lead content. CRTs are the second largest source of lead in Florida’s municipal solid waste stream just behind lead acid batteries. Like Massachusetts, Florida’s strategy includes regulatory streamlining, electronics recycling infrastructure development, time-limited state funding and possibly disposal restrictions to encourage the recycling of end-of-life electronics and especially CRTs. The major difference between Florida’s and Massachusetts’ strategies is the regulatory interpretation. Florida’s interpretation may be a better fit for some states since U.S. EPA Region IV has given preliminary approval to its interpretation of how RCRA applies to CRT management while U.S. EPA Region I has not accepted the Massachusetts approach of exempting unbroken CRTs from RCRA by state rule. The lessons learned from both Florida’s and Massachusetts’ strategies and programs for managing end-of-life electronics can be helpful as other states begin to deal with this emerging environmental issue. APPENDIX I Summary of Florida’s Strategy for Management of End-of-Life Cathode Ray Tubes (CRTs), Computers and Other Electronic Equipment September 2, 1999 Discussion Paper Action Item Summary 1. Specify the Regulatory Framework • Discourage landfilling and encourage recycling of CRTs • Intact CRTs not waste until CRT specialist decides not to repair • Intact CRTs (and even broken/crushed CRTs) from CRT specialist not hazardous wastes when “used or reused as effective substitutes for commercial products” [per 40 CFR 261.2(e)(1)(ii)] in both manufacture of new CRTs (glass-to-glass) or as fluxing agent in secondary lead smelters 2. Promote Recycling Infrastructure: Provide Time Limited Funding • Specific programs funded by $400,000 from SB 1434 • Household Hazardous Waste Collection Center Unique and Innovative Grants • Encourage use of Recycling and Education Grants for CRT/electronics recycling 3. Pilot Programs to Evaluate Various Management Options: Public & Private Partners 3.1. Local/state agency pilot per SB 1434 3.2. Municipal collections • Ongoing dropoff (Pasco County) • One day collections (Alachua County) • Ongoing curbside 3.3. TV repair shops (in cooperation with SWIX) 3.4. Computer repair shops (including schools) 3.5. Electronics demanufacturers 3.6. Computer leasing businesses 3.7. Thrift shops/charities (Goodwill; Salvation Army) 3.8. Moving companies 3.9. Private asset recovery operations 4. Execute State Recycling Contract: Department of Management Services Partner • Available to counties, municipalities and other governmental agencies REFERENCES Environmental Protection Agency, Federal Register: February 24, 1999 (Volume 64, Number 36), Page 9110-9114. Lowry, Jeff, Techneglas, Inc. “Color Television Glass Industry,” presented at Demanufacturing of Electronic Equipment Seminar, October 31, 1998, Deerfield Beach, Florida. Mathews, H.S., C.T. Hendrickson and D.J. Hart, “Disposition of End-of-Life Options for Personal Computers,” July 7, 1997, Carnegie Mellon University, Green Design Initiative Technical Report #97-10. National Safety Council, “Electronics Products Recovery and Recycling (EPR2) Baseline Report: Recycling of Selected Electronic Products in the U.S.,” May, 1999.