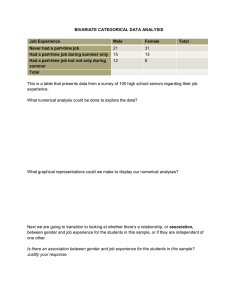

women and flexible working

advertisement