Child Cohort - Growing Up in Ireland

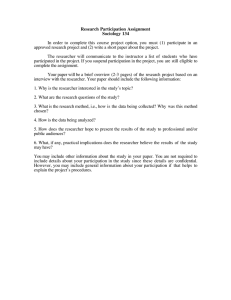

advertisement