Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

www.elsevier.com/locate/buildenv

Diagonal air-distribution system for operating rooms:

experiment and modeling

Monika Woloszyna;∗ , Joseph Virgonea , St1ephane M1elenb

a Centre

de Thermique de Lyon:UCBL, CNRS UMR 5008, INSA de Lyon, bat. 307 20, av. A. Einstein, 69621 Villeurbanne Cedex, France

b Air Liquide, Centre de Recherche Claude Delorme, Jouy-en-Josas, France

Received 19 March 2003; received in revised form 17 March 2004; accepted 24 March 2004

Abstract

The air5ow patterns and the di6usion of contaminants in an operating room with a diagonal air-distribution system were subjected

to both experimental measurements and numerical modeling. The experiments were carried out in MINIBAT test cell equipped with

an operating table, a medical lamp and a manikin representing the surgeon. Air velocity and tracer-gas concentration were measured

automatically at more than 700 points. The numerical simulations were performed using EXP AIR software developed by Air Liquide for

analyzing air quality in operating rooms. Only isothermal conditions were investigated in this comparison with the numerical software.

The results showed that the contaminant distribution depended strongly on the presence of obstacles such as medical equipment and sta6.

? 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Air quality; Air distribution; Contaminant; CFD; Experiment; Numerical simulation; Operating room; Tracer gas; Validation

1. Introduction

The purpose of ventilation systems in health-care facilities

is not only to maximize conditions of comfort, but also to

remove airborne contaminants. The latter task becomes vital

when such contaminants are dangerous for human health, as

is the case for certain bacteria in operating rooms. During

surgery, the patient is at risk of contamination from several sources such as his own body, the surgical team, or

medical instruments. The main way of reducing the risk of

post-operative infection is the strict application of aseptic

procedures, regardless of the ventilation system. In practice,

however, it is impossible to achieve zero contamination in

an operating room. For example, a detailed survey carried

out in 1996 showed that in France 10.5% of nosocomial infections are contracted in an operating room [1].

In order to ensure the most sterile conditions possible

during surgery, and to protect the patient from the contaminants that are present in the air, the air-distribution system in the operating room needs to be carefully designed.

CFD (computational 5uid dynamics) provides a useful way

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +33-4-72-43-6269; fax: +33-4-7243-8522.

E-mail address: monika.woloszyn@insa-lyon.fr (M. Woloszyn).

0360-1323/$ - see front matter ? 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.03.013

of studying air5ows and contaminant distribution patterns

in operating-room applications [2–5]. However, experimental data obtained from model studies of buildings are still

indispensable to the design of air-distribution systems [6].

Therefore a computer program, before being used in predictive calculations, needs to be validated using experimental

results. The analysis of operating rooms is quite a speciJc

problem, due to the presence of obstacles (equipments and

sta6), and the fact that the zone of interest is small. In order

to minimize the risk of infection, a detailed analysis of the

contaminant 5ow close to the patient is more helpful than

the data regarding the overall air5ow pattern.

This study consists of a detailed analysis of the air5ow

patterns and of the contaminant distribution in an operating

room, using both experimental and numerical methods. In

this Jrst investigation only isothermal conditions are of interest, so the thermal buoyancy e6ects are not taken into account. The objective was to develop a reliable predictive numerical tool for operating-room applications. The Jrst part

of the project consisted of an experimental study of contaminant distribution. Such experiments being diKcult to perform in situ, mainly because of the sterility requirements and

the presence of complex medical apparatus, we decided to

set up a life-size experimental model of an operating room,

using an existing test cell, the MINIBAT. The numerical

1172

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

simulations in the second part of the project were performed

using EXP AIR software developed by Air Liquide [7] for

the analysis of air quality in operating rooms.

2. The experiment

2.1. The MINIBAT test cell

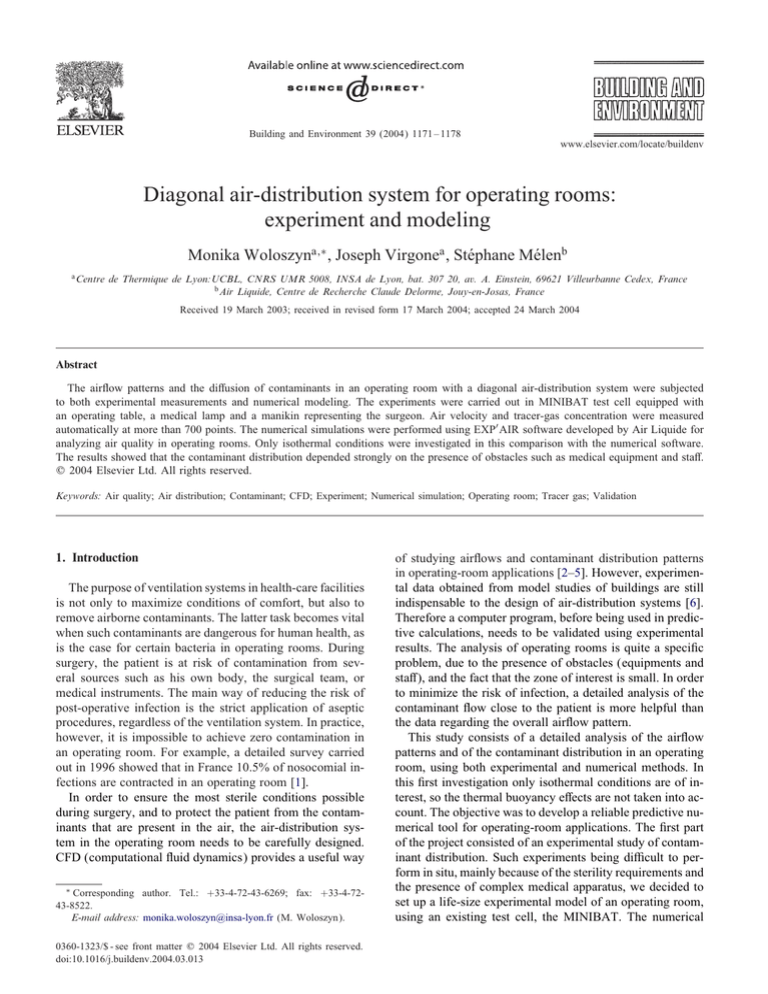

The Centre de Thermique de Lyon (CETHIL) owns a

full-size test cell, the MINIBAT, which was speciJcally designed for the detailed measurement of air5ows in Jxed conditions. This facility comprises two identical cells (Cell 1

and Cell 2) which measure each 3:10 × 3:10 × 2:50 m3 (see

Fig. 1). Cell 1 is separated by a glass wall from the climatic

chamber, whose air-treatment system can produce temperatures of between −10◦ C and +30◦ C. The thermal guard is

maintained at a uniform temperature of 20◦ C to represent

adjacent spaces.

The MINIBAT is equipped with sensors for measuring

surface and air temperatures, air velocities and tracer-gas

concentrations. Relative air humidity and operative temperature are measured near the center of each cell. Both cells

are also equipped with an automatic device that moves the

sensors over di6erent vertical planes. This device consists of

3 motors which actuate a metal arm on which is mounted an

array of 6 sensors: 2 K-type thermocouples for air temperatures, 2 omnidirectional hot-wire probes for air speeds, and

2 measuring points for gas concentrations. Tracer-gas concentrations are measured using a BrNuel and Kjaer analyzer

[8]. The precision of the results obtained in the MINIBAT

was ±0:3◦ C for air temperatures, 3% for air velocities higher

than 5 cm=s, and 4% for tracer-gas concentrations [9].

Fig. 2. Diagonal air-distribution system in the Hôtel Dieu hospital, Lyon,

France.

The air5ow can be either turbulent or laminar (i.e. unidirectional), and additional devices, such as air curtains or partitions, can also be used. Some examples of existing systems

are discussed in detail by Pfost [11], Horworth [12,13] and

Lewis [14].

The eKciency of an air-distribution system in preventing nosocomial infections depends on factors such as the

position of the air inlet and outlet, the air-inlet velocity or

air-change rate, the presence of air5ow-perturbing elements

(equipment, sta6) and the type of operation being performed.

In order to construct a realistic model of an operating

room, some measurements were taken in the Hôtel Dieu hospital in Lyon, France, whose operating room was equipped

with a diagonal-type ventilation system, with two air inlets in the ceiling, though not directly above the operating

table ([15], see also Fig. 2). The outlet was situated in the

lower part of the wall. The inlet air velocities were 3.9 and

2:15 m=s. The air velocities close to the operating table were

too low to measure (¡ 0:1 m=s). The air temperature varied

according to the surgeon and the type of operation, but the

most common values were in the range 19–20◦ C.

During the in situ visit, in addition to the air-distribution

system, and as already reported in the literature, 3 other

elements were found to a6ect the air5ow patterns.

2.2. Experimental model of an operating room

2.2.1. Key components

Air-distribution systems for operating rooms are of several di6erent types. According to [10] it would seem that

the delivery of air to the upper part of the room, with the

exhaust located on the opposite wall, is probably the system

that gives the lowest concentration of contaminant. The air

inlet can be situated either right above the patient (central

air distribution) or to one side (diagonal air distribution).

• The operating table.

• A lighting system speciJcally designed for operating

rooms, which concentrates light on a small area (up

to 100,000 lux on an area of 100 cm2 ) with a color

Thermal guard

Glass wall

Median

Air Inlet

Z

Sensors

Y

cell 1

Climatic chamber

cell 2

Door

X

Concentration

Air Velocity

Air Temperature

Vertical Displacement

Horizontal Displacement

Lateral Displacement

Fig. 1. The MINIBAT test cell.

cell 1

Air Exhaust

Pollutant

injection

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

A

B

C

A

air

inlet

table

manikin

1173

lamp

air

outlet

air

inlet

C

B

table

M

M

air

outlet

lamp

contaminant

injection

point

manikin

A

B

C

A

B

contaminant

injection

point

C

Fig. 3. The experimental set-up. (a) Horizontal view and (b) cross section at MM.

temperature above 3000 K, but with limited heat emission

in the illuminated zone. The lamps are in general placed

between the clean-air inlet and the patient.

• The medical personnel, who act as mobile obstacles

between the air inlet and the patient, and are a source

of contaminant. Their shapes and movements are impossible to represent accurately, but other parameters can be taken into account in the experimental

model.

2.2.2. Main features of the experimental model

Cell 1 of the MINIBAT was used to model operating-room

conditions.

The air exhaust was positioned in such a way as to produce diagonal air distribution. The ventilation air 5ow was

set at around 100 m3 =h so as to obtain an air velocity close

to 2:5 m=s at the air inlet, in order to represent real situation. Real velocity values were used rather than air-change

rate, because though both parameters had an impact on air5ow patterns, it was found that at higher values, air-change

rates had little in5uence on the eKciency of the ventilation

system [16].

The inside of the cell was equipped with:

• a wooden table measuring 2:00 × 0:47 × 0:14 m3 , with a

parallelepiped support 1:40×0:70×0:27 m3 , both painted

matt white;

• a manikin, i.e. a metal parallelepiped 0:20 × 0:30 ×

1:70 m3 , with its external surface painted black, representing a surgeon;

• a low-temperature lamp (PrismAlix 4003 S, obtained from

Air Liquide Healthcare), situated 1:12 m above the center

of the table.

The contaminant was represented by a stream of tracer gas

coming from the manikin’s “mouth”, at a height of 1:52 m.

The tracer-gas 5ow rate was 15 ml=min. Sulfur hexa5uoride

(SF6 ) was used because it is detectable at low concentrations

and does not react chemically with air. It is also heavier than

Fig. 4. The test cell.

air, and in this respect behaves in a similar way to the most

common air pollutants [17].

The experimental conJguration is shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

During the experiment, in order to ensure isothermal conditions, the temperatures of the thermal guard, the inlet air

and the climatic chamber were maintained at 20◦ C, and there

was no active heat source in the test cell.

The climate in the test cell (tracer-gas concentrations, air

velocities and temperatures) was measured at several points

on 4 vertical planes, as shown in Fig. 3:

• a longitudinal plane MM, between the air inlet and

outlet;

• three lateral planes:

◦ AA: between the manikin and the operating table;

◦ BB: between the operating table and the lamp;

◦ CC: between the operating table and the air outlet.

For these 4 planes the measurements were carried out on a

15 × 15 cm2 grid, except close to the manikin and the table,

where a 7:5 × 15 cm2 grid was used in order to achieve

1174

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

greater precision near the perturbing elements. The grid sizes

were chosen on the basis of previous work carried out in the

MINIBAT [9]. Finally, more than 700 measurement points

were used to characterize 3-dimensional (3D) Jelds of air

velocity and tracer-gas concentration.

2.5

air

inlet

1

1.72

1,

1,4

1,6

1.19

1,5

1,3

1,1

0.9

0.8

0.6

0.5 0.4

0.2

0.3

2

lamp

0

manikin

Z (m)

1.5

3. Numerical model

0.7

0.1

table

1

3.1. EXP AIR software

The EXP AIR is a CFD program based on a Jnite-volume

discretization of Navier Stokes equations [18] adapted to

3D simulations of indoor climate. EXP AIR is dedicated

to clean room applications; it is a reworked version of the

general CFD program ATHENA [19,20,21] developed by

Air Liquide. The simulated domain is Jnely discretized using an orthogonal mesh system, in order to reduce computational time. The coupling between velocity and pressure

is ensured by the well-known SIMPLE algorithm. The numerical results from EXP AIR have already been successfully compared with experimental measurements for natural

convection in a 2D case, and for forced convection in an

empty 3D enclosure with a low ventilation rate [21], and

the program has also some post-treatment features, such as

easy visualization of air or contaminant paths, which make

of it a valuable tool for the precise analysis and design of

air-distribution systems.

3.2. Numerical model

EXP AIR was used to model MINIBAT’s Cell 1,

equipped with diagonal ventilation, operating table, manikin

and lamp (see Section 2).

The turbulence model used here was the 2-equation standard k– model, which is well suited to the simulation of

indoor environments. The 5ows near the boundaries were

represented by using the standard logarithmic law [22].

SF6 concentrations were calculated using the conservation equation adapted to heavy gases. The model used

in EXP AIR for the description of contaminant 5ows

came from the DISPAL program, which was designed for

use in the simulation of contaminant distribution in open

spaces [23].

4. Case study: experiment and modeling

4.1. Experiment

The wall and the thermal-guard temperatures, as well as

the inlet and outlet rates, were kept steady for the duration of

the experiment (which lasted several days). In the occupancy

zone, the measured temperatures were between 20:3◦ C and

20:5◦ C. It can therefore, be considered that the cell was

isothermal.

air

outlet

0.5

0

0.5

0.75

1

1.25

1.5

1.75

2

2.25

2.5

2.75

Y (m)

Fig. 5. Iso-velocities measured in the MM plane (m/s).

2.5

60

40

air inlet

2

80

manikin

lamp

1.5

X (m)

100

contaminant

source

table

1

160

200

260

240

180

140

air outlet

0.5

120

0

0.5

220

0.95

1.4

1.85

2.3

2.75

Y (m)

Fig. 6. Iso-concentrations measured in the MM plane (mg=m3 ).

The most interesting results were those for air velocities

and tracer-gas concentrations. The iso-value plots presented

in this section were produced using EES software [24].

Fig. 5 shows the air velocities in the cell. The ventilation

jet at ceiling level can be clearly seen. In front of the manikin,

between the table and the lamp, the air velocity was very

low (¡ 10 cm=s).

The tracer-gas concentrations in the cell are shown in

Fig. 6. Two important pockets of SF6 can be seen in front of

the manikin: one close to the table, the other at 5oor level.

This illustrates the downward di6usion of SF6 , and conJrms

the existence of an almost-immobile air zone, as detected

by air-velocity measurements.

4.2. Modeling

The air5ow and the contaminant distribution in the MINIBAT were simulated using the EXP AIR software. In order

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

1175

idates (or even renders impossible) numerical simulations.

In the present case, however, a numerical convergence was

reached, and the computed values were in good agreement

with the experimental measurements (see Section 4.3 for

more details).

4.3. Experimental and numerical results: discussion

Fig. 7. SF6 concentration cartography in the MM plane simulated with

EXP AIR (mg=m3 ).

to produce a realistic description of the air5ow, a good definition of the boundary conditions was very important. The

representation of the air inlet was the focus of our interest due to its essential impact on the overall air-distribution

pattern. Several methods are to be found in the literature

for representing correctly the boundary conditions at the air

inlet [25]. The best results have been obtained using a detailed description of air-inlet geometry, representing accurately the grid [26]. However, the Jneness of mesh needed to

perform these calculations and therefore the computational

time make this approach impractical. Other methods have

been suggested, generally based on a simpliJed model of

the air inlet, without the grid, but with the same essential

characteristics (5ow, e6ective area and aspect ratio). This

model was compared with more sophisticated approaches

by International Energy Agency Annex 20, with encouraging results [26,27]. Moreover, the e6ect of the turbulent intensity was found to be less signiJcant than the description

of dynamic conditions.

In the MINIBAT, an industrial air vent, equipped with

horizontal and vertical grids, is used as the air inlet. As a

detailed description of grid geometry was not possible in

the present case, the basic approach for the representation

of boundary conditions was used. In order to assess the

parameters of the simpliJed jet (neglecting the perturbing

impact of the grid), preliminary simulations were conducted

using the commercial CFD program Fluent [28]. The inlet

boundary conditions used as input parameters in EXP AIR

simulations were determined by comparing the measured

and 5uent-simulated shapes of the air jet.

The SF6 concentrations in the medium plane were calculated by EXP AIR, as shown in Fig. 7, and the strongest concentration found at the source was 22; 118 mg=m3 , while the

average value was around 100 mg=m3 , and close to the air

inlet the program computed a value of 0:27 mg=m3 . Such a

di6erence, i.e. some 6 orders of magnitude, in general inval-

Fig. 8 shows the measured and calculated air velocities in

the median MM plane. Except for the highest velocity values for the Jrst 2 proJles (at X = 0:53 m and at X = 0:6 m

from the wall and close to the air inlet), there was very

good agreement between experimental and numerical results. Clearly, the experimental air jet from the inlet, which

follows the ceiling to the opposite wall, is accurately represented. There is a small rise in the simulated velocity proJles

at medium height between the table and the air outlet (for

X ¿ 2 m), which illustrates the recirculation of the air and

is in keeping with the experimental conJguration. Slightly

higher air-velocity values close to the 5oor for X ¿ 2:1 m,

in both the numerical and experimental proJles, show the

in5uence of the air outlet.

The di6erence between the maximum air-velocity value

for the proJles at X = 0:53 and 0:6 m is due to the way

the model represents the air inlet. As mentioned in Section

4.2, a simpliJed model, neglecting the perturbing e6ect of

the grid, was used in this study. Allowing for some imprecision in the local description of the air jet, this basic

model gives a correct representation of the overall air5ow,

keeping the computational time within reasonable limits. A

more detailed representation of the air inlet would improve

the description of the jet at the air inlet, but would also require much more computational capacity and time. Despite

the imprecision in the local representation of the air jet, the

model was satisfactory for the purpose of our study. Indeed,

the overall air5ow pattern distribution in the cell, as simulated with EXP AIR, as well as the description of the zone

of main interest between the operating table, the manikin

and the lamp was in good agreement with experimental

measurements.

The comparison between the measured and simulated contaminant concentrations in the median MM plane is shown

in Fig. 9. There is quite good overall agreement between

the measured and the simulated values, but the di6erence is

a little higher for the concentration proJles than for the air

velocities, mainly due to numerical factors. The SF6 concentrations presented in Fig. 9 are between 50 and 300 mg=m3 ,

which is much less than the maximum concentration of

22; 118 mg=m3 registered close to the source (by a factor of

100), i.e. the degree of relative precision of numerical simulation is satisfactory. Moreover, the overall distribution of

the contaminant is well represented by EXP AIR (compare

Figs. 6 and 7).

From Figs. 6, 7 and 9, it can be seen that the contaminant concentration was at its highest just below the point of

1176

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

Fig. 8. Velocity proJles in the MM plane (m/s) for di6erent positions of X (between the air inlet and outlet), as calculated with EXP AIR (—) and

measured (•).

injection, between the manikin and the table. The gas followed its natural tendency to downward di6usion, indicating

that the air movements in this zone were too weak to ensure

e6ective mixing. The result was a high concentration of the

contaminant just above the table, which in real conditions

would be undesirable.

Such “pockets” of contaminant are clearly due to the presence of obstacles which perturb air5ows. This is conJrmed

by the fact that in previous work on diagonal ventilation in

the empty MINIBAT test cell, the contaminant was found

to be quite homogenously distributed [21].

5. Conclusions

The experimental and numerical results of the present

study clearly show that the distribution of the contaminant

in an operating room, and therefore the risk to patient, de-

pends on the geometrical parameters of the room, such as the

position of the air inlet and outlet, the contaminant source,

and objects that could perturb the air5ow. For a diagonal

air-distribution system, the results presented here show that

the obstacles in the occupancy zone had a signiJcant in5uence on the distribution of the contaminant. Indeed, even

when the air velocity at the inlet was high (around 2:5 m=s),

the air in the occupancy zone was almost immobile. It can

therefore be seen that, for a Jxed source, the distribution of

the contaminant depends on the position of obstacles (equipment and sta6).

A correct representation of the contaminant distribution

in the presence of obstacles is thus an essential characteristic of a numerical program, whose purpose is to simulate

air-distribution patterns in operating rooms. The results of

the EXP AIR simulations presented here are close to the

experimental measurements, showing that EXP AIR, which

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

1177

It will be interesting, in a future work, to analyze the

thermal buoyancy e6ect. It will be necessary to consider

the in5uence of the heating sources: the surgeon power, the

patient one, the lamp.

References

Fig. 9. SF6 concentration proJles in the MM plane (mg=m3 ) for di6erent

positions of X (between the air inlet and outlet), as calculated with

EXP AIR (—) and measured (•).

includes now a dispersion model adapted to heavy gases

and an adequate representation of the air inlet, is well suited

to detailed design and analysis of diagonal air-distribution

systems for operating rooms.

With such a diagonal ventilation system, the pollutant

goes down and the patient receives the possible contaminants coming from the medical sta6. A better solution would consist in an air inlet at the bottom of the

room and an exhaust near the ceiling: in such a case,

contaminants would be extracted without falling on the

patient.

We should also point out the diKculties involved in the

experimental study of air5ow patterns in operating rooms.

Even in laboratory conditions, detailed measurements using

traditional techniques are impossible, due to low air-velocity

values. If air-distribution patterns are to be studied in the

kind of situation dealt with in the present study, where there

is a zone in which air velocity is too low to be measured

by normal type of sensors (5 cm=s for hot-wire probes), an

alternative method must be used, e.g. based on tracer-gas

measurements or CFD simulations.

[1] CTIN. Enquête Nationale de Pr1evalence des Infections Nosocomiales,

Mai-Juin 1996 Comit1e Technique national des Infections

Nosocomiales—Secr1etariat d’Etat aU la Sant1e et aU la S1ecurit1e

Sociale. Direction G1en1erale de la Sant1e. Direction des Hôpitaux.

June 1997.

[2] Depecker P, Rusaouen G, Inard C. Study and comparison of two type

of air 5ow in operating rooms using a CFD code. In: Proceedings

of Building Simulation 95, IBPSA, Madison, USA.

[3] Tinker JA, Roberts D. Indoor air quality and infection problems in

operating theatres. Proceedings of EPIC 98:285–90.

[4] Chow T-T, Ward S, Liu J-P, Chan FC-K. Air5ow in hospital

operating theatre: the Hong Kong experience. In: Proceedings of

Healthy Buildings, vol. 2, 2000. p. 419–24.

[5] Air Liquide Sant1e. L’1ere de l’a1eraulique. HMH, June 2001.

[6] Awbi HB. Ventilation of buildings. London: E& FN Spon; 1991.

313pp.

[7] Air Liquide Sant1e. Dossier technique Exp Air. ed. ALS. 2001.

[8] Bruel & Kjaer. Multipoint Sampler and Doser Type 1303 Instructions

Manual. 1991.

[9] Laporthe S. Contribution aU la qualiJcation des systUemes de ventilation

des bâtiments: int1egration d’1el1ements perturbants. ThUese de doctorat,

INSA de Lyon, 2000. 237pp.

[10] ASHRAE Application Handbook ch 7: Health Care Facilities. 1999.

[11] Pfost JF. A Re-evaluation of laminar air 5ow in hospital operating

room. Ashrae Transactions 1981;87(2):729–39.

[12] Horworth FH. Prevention of airborne infection during surgery.

Ashrae Transactions 1985;91(1b):291–304.

[13] Horworth FH. Prevention of airborne infections in operating rooms.

Hospital Engineering 1986;40(8):17–23.

[14] Lewis JR. Operating room air distribution e6ectiveness. Ashrae

Transactions 1993;99(2):1191–200.

[15] Wecxsteen H, Kastally M, Woloszyn M, Virgone J, Laporthe S.

Travaux Exp1erimentaux en vue de Valider un Code de Description

des Ecoulements d’Air Int1erieur. Rapport Jnal, Convention Insavalor

- Air liquide, no 6715, 2000.

[16] Castanet S. Contribution a1 l’1etude de la ventilation et de la qualit1e de

l’air int1erieur des locaux. ThUese de doctorat, INSA de Lyon, 1998.

289pp.

[17] Laporthe S, Virgone J, Castanet S. Comparative study of two

Tracer Gas: SF6 and N2 O. Building and Environment 2001;36(3):

313–20.

[18] Patankar SV. Numerical heat transfer and 5uid 5ow. London:

McGraw-Hill; 1980.

[19] Champinot C, Till M, Philippe L, Perrin V. Numerical modeling as

a decision making tool. Verre 1999;5(2).

[20] Shamp D, Marin O, Champinot C, Jurcik B, Joshi M, Grosman R.

Oxy-fuel furnace design optimization using coupled combustion/glass

bath numerical simulation. Conference on Glass Problems, October

1998.

[21] Melen S. Validation du code EXP AIR v4.4. Air Liquide technical

repport, 2001.

[22] Launder BE, Spalding DB. Mathematical models of turbulence.

London: Academic Press; 1972.

[23] Melen S. Notice th1eorique DISPAL v4.0—logiciel de dispersion

tridimensionnelle. Air Liquide technical repport, 1997.

[24] Klein SA, Alvarado FL. EES: Engineering Equations Solver.

Copyright 1992–2001 [http://www.fchart.com].

1178

M. Woloszyn et al. / Building and Environment 39 (2004) 1171 – 1178

[25] Teodosiu, C. Mod1elisation des systUemes techniques dans le domaine

des e1 quipements de bâtiments aU l’aide des codes de type CFD. ThUese

de doctorat, INSA de Lyon, 2001. 355pp.

[26] Emvin P, Davidson L. A numerical comparison of three inlet

approximations of the di6user in case E1 annex 20. Proceedings

of the Fifth Roomvent Conference, vol. 1. Yokohama, Japan, 1996.

p. 219–37.

[27] Heikkinen J. Modeling of supply air terminal for room air 5ow

simulation. Proceedings of the 12th AIVC Conference, vol. 3.

Ottawa-Canada, 1991. p. 213–30.

[28] Fluent Inc, 5uent user’s guide, vol. 5.0. Lebanon—NH(USA): Fluent

Inc; 1998.