Babbling Brook Issue 2

advertisement

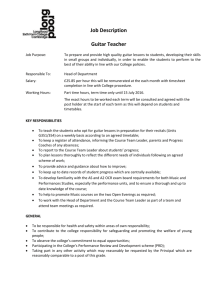

news. music. players. instruments. Babbling issue 2 spring 2013 The guitar Jack built... Brook takes its custom building to ‘nouveau’heights, with this very special model (left). To find out more about the project – and the Easterbrook Art of Inlay – see page 2... Welcome... ...to the second edition of ‘Babbling Brook’, our online magazine for all things ‘Brook Guitars’. Hard to believe that almost a year has gone by since the first issue was launched – but there’s been lots going on at our workshops since then... wonderful singer-songwriter Phil Bird – and much more. As always, we value your opinion and would love to hear from you, so call or email to tell us what you think of ‘Babbling Brook’ – and who knows, we could even discuss your ‘next guitar’! Cheers... ...not least of which is the stunning custom Taw you can see here! Also featured in this issue are two longtime friends of ours – Steve Yates, a stunningly original and award-winning fingerstyle composer/guitarist, and the Simon and Andy Founders, Brook Guitars page 2 www.brookguitars.com Brook Taw It is, quite simply, the most stunningly ornate custom Brook guitar ever built at the Easterbrook workshop. Here, its creator Jack Smidmore describes how he found inspiration in the work of Czech Art Nouveau painter and decorative artist Alphonse Mucha – and reveals a few secrets about the fine art of inlay... continued on page 3 www.brookguitars.com page 3 I ’D been thinking about making a really special one-off guitar for six or seven months. I knew at the outset that I wanted to cover it with my inlay work, but I also wanted the design of the inlays and guitar to work together as a whole. The headstock and back inlays were based on a painting called ‘Dance’ (see page 4) and luckily, Mucha’s work is in the public domain! After working on the main inlays I designed the rosette, loosely basing it on another Mucha ‘nouveau’ border, then the heel cap and finally, the position markers. Originally, my plan was to make a Creedy, as I thought that a traditional parlour size guitar would suit the whole Art Nouveau idea, but the back inlay really didn’t suit the Creedy shape, and by this point I had decided I wanted to repeat the ‘Dance’ inlay on our standard flat headstock. I really like the shape of the Taw – I have one myself at home – with its tight waist and wider lower bout I felt the inlays worked the best with continued on page 4 “ The project was very much a one-off, but I really do hope that the guitar as a whole is appreciated not just as something to be looked at in a glass case, but also played... “ I started to think about Art Deco or Art Nouveau as the style or theme and began to research the Internet for some inspiration. I stumbled across Alphonse Mucha’s work and basically fell in love with it: fantastic, stylish, colourful painting and design, and I could also see that there was a lot of potential to adapt his work to make some beautiful inlays. page 4 www.brookguitars.com Brook Taw Inspiration behind the instrument from page 3 ALPHONSE Maria Mucha (above) was born in the town of Ivanãice, Moravia (the present Czech Republic) in 1860. this model. As for the sound, the Taw isn’t one of our larger models, but it produces a great sound that suits different styles of playing. I’m quietly confident that this one will too. Drawing had been his main hobby from childhood, and following high school he worked at decorative painting jobs in Moravia, mostly painting theatrical scenery, before taking up freelance decorative and portraiture. I had to make a decision about what woods to use for the back and sides before I started the rest of the inlay work, because I’d decided that whatever wood I chose would be used for the inlays too. Again, the idea was that although the guitar would be covered in inlays, I wanted the design to work as a whole, to be beautiful but subtle at the same time. We had recently cut up 11 sets of bubinga, which just seemed to arrive at the right time and perfectly fitted the bill. Bubinga is quite a hard, stiff wood with a rich dark orange/red colour; it’s nicely flamed and worked really well with the black ebony that we used for the bindings, fingerboard and bridge. So, apart from the back and headstock inlay, the repeated use of bubinga and ebony would provide the red and black theme that appealed to me; the front is a beautiful, highly-figured set of Alpine spruce that is perfectly book-matched; and the laminate neck is flamed sycamore with a bubinga and ebony centre stripe, along with a stacked decorative heel. The approach I took with the bracing was to try to do as little different from standard as possible, to be honest. We’ve made over 1,000 guitars now Moving to Paris in 1887, Mucha produced magazine and advertising illustrations. Around Christmas 1894, he happened to go into a print shop where there was a sudden and unexpected need for a new poster advertising a play featuring the famous actress Sarah Bernhardt. Mucha volunteered to create a lithographed poster, and Bernhardt was so impressed with the result that she began a six-year contract with Mucha. and know what works, so apart from one extra back brace to add a little support under the large back inlay, all the internal bracing, blocks, linings etc. are all as standard. The back’s only slightly thicker than normal, but since the bubinga is quite stiff and the back is pressed into a curve, I'm confident that the inlay won’t adversely affect the structural integrity or tone of the instrument. In total, there are 16 individual inlays on this guitar; the back inlay alone consists of 83 individual pieces and the headstock has 62. Unfortunately, there wasn't enough room to use the Brook logo in its usual position on the head veneer inlay so I incorporated ‘Brook’ into the 12th continued on page 5 Mucha went on to produce a flurry of paintings, posters, advertisements, and book illustrations, as well as designs for jewellery, carpets, wallpaper, and theatre sets in what was termed initially ‘The Mucha Style’, but became known as Art Nouveau (French for ‘new art’). His works frequently featured beautiful young women in flowing, vaguely Neo-classical-looking robes, often surrounded by lush flowers which sometimes formed halos behind their heads. Mucha’s work has continued to experience periodic revivals of interest for illustrators and artists. Interest in Mucha’s distinctive style was strong during the 1960s (with a general interest in Art Nouveau) and is particularly evident in many psychedelic posters. More recently, Japanese manga artists Naoko Takeuchi and Masakazu Katsura have mimicked his style several times, while former Marvel Comics Editor in Chief Joe Quesada also borrowed from Mucha’s techniques for a series of covers, posters, and prints. (Right) ‘Dance’, the original Mucha painting which inspired Jack’s stunning Brook Taw Nouveau www.brookguitars.com page 5 Brook Taw from page 4 fret position marker inlay. The inlay work alone took around 100 hours over about three months, on top of the 80 hours that we estimate goes into the construction of one standard instrument. The guitar is now on display at Ivor Mairants in London, and is for sale at £5,500, if anyone fancies taking a closer look and trying it out! That’s obviously a lot of money, but it is a very special guitar – I certainly wish it was mine. The project was very much a one-off, but I really do hope that the guitar as a whole is appreciated not just as something to be looked at in a glass case, but also played. I must admit that I haven’t given her a name, I’ve just been calling her ’Taw Nouveau, style 020’ – or perhaps it’s just that I don’t want to get too attached to her! (Above) Jack strums the first few chords on his one-of-a-kind custom Taw The guitar Jack built... z Bear-claw Engelmann top z Figured bubinga back and sides z Figured maple, bubinga and ebony laminated neck z Ebony fingerboard, bridge and head veneer z Ebony binding with bubinga purfling z Waverly tuners z Bone nut and saddle z Elixir Polyweb Light strings I must admit that I haven’t given her a name – or perhaps it’s just that I don’t want to get too attached to her... page 6 www.brookguitars.com A selection of some of the inlay work carried out by Jack over the last 12 years... Custom builds are the lifeblood of Brook Guitars. From a slight variation on a ‘standard’model’s spec to the choice of timbers used, there are many ways to make a guitar uniquely your own. But when it comes to personalising your instrument through its inlay, that’s where Jack Smidmore, Brook’s resident expert, comes in... Interview: Martin Bell. HERE was a time when simple dots on the fingerboard and the occasional headstock logo were the extent of the ‘decoration’ to be found on the average guitar. Notable exceptions were, of course, Gibsons – reknowned for the slabs of abalone and ‘signature’ trapezoid inlays on many of their instruments – whilst the level of inlay on a Martin has always been traditionally increased proportionate to the price tag of the model concerned! The fine art of consigned to a glass case, or – worse still – a hermetically-sealed vault, locked away as a valuable collector’s item. Then there are those for whom an inlay design affords them the opportunity to personalise an instrument in a completely unique way, whether through something Today, however, the ‘art of inlay’ has reached new heights, developing as it has in close parallel to the increasingly high standards that many modern luthiers continue to set in their work. At one end of the scale are the elaborate designs that span the entire surface of a fingerboard, front and/or back of a guitar; arguably, such instruments are rightly considered works of art in themselves, though – sadly – seldom destined to be played, heard and enjoyed in public. Instead, they are more likely to be Raw materials: some of Brook’s stock of abalone and mother-ofpearl, in its natural state as simple as their initials at the 12th fret – or a more poignant motif/illustration. At Brook, Jack Smidmore has carved out his own niche as ‘inlayer-in-chief’ during the past 12 years, initially beginning with... continued on page 7 www.brookguitars.com page 7 The fine art of from page 6 initials (!), and working towards the stunning Brook Taw Nouveau featured in this issue. I started by asking Jack whether he had undergone any formal/informal art training, before or since joining the Brook team... JS: Apart from a GCSE in graphic design I have had no formal training, I have always been artistic and spent many years drawing before I started doing the inlay and marquetry work. I’m proud of all my work, whether it’s a really complex piece, some fine lettering or a fantastic combination of woods... Left (from top): Bullrushes and dragonfly design, from an original concept by customer Steve, from South Devon; Tranors/cranes inlaid into the rear of the headstock of a custom ‘Tidan’ for Daniel in Sweden; Rocky Mountains High – a recreation of the Colorado range for John Denver fan/Midlands singersongwriter Mark Robinson Tiger, tiger: Jack has earned his ‘stripes’ at Brook with work such as this... Bottom: The Larry Robinson book that first inspired Jack’s work MB: How did you first get into the inlay work? JS: The inlaying came about solely through work; I think the first inlay I attempted was maybe a customer’s initials on the 12th fret, probably about 12 years ago now. From there, it would just be small things like that, a logo here, a name there, a flower, a Celtic knot. At first I found the whole process quite stressful, and I was basically learning as I went along. After spending years drawing as much detail into my pictures as I could with depth and shadow, drawing every hair etc., moving onto inlays with solid lines, edges and a limited area to work with was frustrating. Over the years I’ve realised that inlay/marquetry work is just a totally different craft. I’m now much more confident with my design, cutting and use of materials. MB: What is the most unusual/bizarre request you’ve had to personalise a guitar with inlay? And is there anything you’ve ever been asked to do that’s not been possible, or that you’ve refused? JS: There have been things that customers have wanted that I just couldn’t do and I must say that I do prefer to work on my own designs. But if I can work out a design based on a customer’s suggestion and it’s what they want, then I’ll do it. I’ve worked on all kinds of different designs over the years: birds, dragons, gargoyles, mountain ranges, skulls, dolphins, trees, wolves, leaves, flowers, tigers, cats, horses, knots, names, faces – and even a complex copy of a customer’s tattoo. continued on page 8 page 8 www.brookguitars.com The fine art of from page 7 MB: ...and what about the simplest? JS: Not sure I’ve done one of those yet! MB: What are the challenges – technical or otherwise – in producing fine inlay work such as yours? JS: There are three parts to my inlay work; the design, the selection of materials & the cutting. As long you get those things right it’s easy! No, it all starts with the design. An inlay is essentially just a complex little jigsaw puzzle, pieces have solid edges that don’t blend and as I don’t do any engraving on my work all the lines of detail are cut in using a saw. Over the years, I’ve worked out what level of detail is possible, how to use shadow and create depth. Material selection is important for creating depth and detail too, how a particular piece of abalone reflects the light from the viewing angle or how the grain or flame in a piece of wood can add texture or detail to a design. The thing I most like about my finished inlay work as opposed to my Some of my latest work is based from source photos. After printing out a picture, I’ll lightly trace then re-draw it, dividing it up into sections... drawing is the addition of colour, wood is beautiful and my preference for inlay work. As for things going wrong, I try to design an inlay that I will be able to cut but the cutting is the really hard bit, it’s a case of having to get it right – or being prepared to start that bit again. MB: What sort of depths/thicknesses of materials are you working with? And does an intricate fingerboard inlay create any problems when it comes to re-fretting, or adjusting the relief on a neck? Does it have to be able to ‘bend’ with the wood, for example? JS: I thickness my wood veneers to 2.2mm but after sanding they end up just under 2mm. The abalone and Mother of Pearl comes in smaller pieces and tends to be thinner, around 1.5mm. When the guitar goes together, the neck is glued on and left to settle for a couple of days. We’ll then level the fingerboard and take out any humps or dips, before routing out the cavity for the inlay. As I initially leave my inlays loose, they take on the camber of the fingerboard before we glue and fill around them, prior to the frets going in. That does mean that when we eventually come to do a re-fret it’s less likely we’ll sand through the inlay. Pencil-drawn examples of the artistic skills and attention to detail Jack puts into his inlay work MB:To create a design such as, for example, the tiger, the tranors/cranes or the ‘nouveau’ guitar, where do you start? Do you trace over an continued on page 9 www.brookguitars.com page 9 The fine art of (Right) Jack uses a jeweller’s saw to cut out the intricate pieces of an inlay design, and early alternative headstock designs for the ‘Brook Taw Nouveau’ from page 8 original ‘source’ picture and work from there, or is everything done completely ‘by eye’? JS: I draw out my designs in both of those ways to be honest. All of the ‘nouveau’ guitar inlay work was drawn out freehand, trying to copy the Mucha ‘Dance’ design as closely as I could. The sound hole, V, position markers etc were drawn out with pencil until I was happy with the designs. The tiger inlays and some of my latest work is based more from source photos. After resizing, editing and printing out the picture, I’ll lightly trace the outline using a light box, then redraw the image dividing it up into sections and deciding what changes I want or need to make to the design as I go along. MB: Aside from your fabulous ‘Taw Nouveau’ project, what inlay work are you most proud of over the years? JS: I’m proud of all of my work, whether it’s a really complex piece, some fine lettering or a fantastic combination of woods….the truth is – I’m most proud of the last inlay that I complete and hopefully the next one I finish will turn out to be the one that I am most proud of! MB: Are you hoping that the ‘art nouveau’ guitar will be a ‘player’s instrument’, or do you see it more of a ‘collector’s item’? It’s definitely not the sort of guitar I’d feel comfortable handing around in the pub, for example! JS: I know what you mean, the guitar is very much a one-off but I do hope that the guitar as a whole is appreciated as not just as something to be looked at but also played. MB: Have you been inspired by any other makers’ inlay work (eg Larrivee, William ‘Grit’ Laskin etc)? (From top) The work of William ‘Grit’ Laskin, Jimmi Wingert and CF Martin JS: Larry Robinson’s work is great, he’s been doing inlay work for longer than I have been alive and it was his ‘The Art of Inlay’ book that first inspired me and showed me the sort of thing that could be done. I also like Jimmi Wingert’s work, but as for whose work I really admire, it would have to be ‘Grit’ Laskin’s stuff, which is absolutely incredible. MB: I’m asking you to play ‘devil’s advocate’ slightly now – there are some stunning examples of the ‘art of inlay’ to be found on so many instruments – the millioneth Martin guitar, for example, and some of the Grit Laskin guitars, where there’s so much inlay involved, no wood is even visible. But is there a ‘good taste’ line that’s sometimes crossed – albeit in the name of creating a true collector’s instrument? What are your thoughts? JS: After making the ‘Taw Nouveau’ this might sound a bit of a contradictory answer but, yes, I DO think there is a ‘good taste’ line that is often crossed! I’m personally not very keen on guitars with A LOT of abalone inlay work; I can certainly appreciate the craftsmanship and work that has gone into these ‘shiny’ guitars, but I do often wonder what an instrument with as much pearl inlaid directly into the wood sounds like. I love the way Grit Laskin uses the head veneer and fingerboard as a canvas for work that is interesting, well-designed and incredibly executed, but there is something about how abalone & Mother of pearl sits with any wood other than ebony that I’m not so keen on... MB: And finally, what project is next on the cards? JS: One of my Harris Hawk headstock inlays is going to be used on a stock Taw that’s making its way through the workshop now. Other than that, I’m usually either working on a customer’s inlay at work, a possible future customer’s inlay at home or a new design. At the moment, I have a selection of designs ready to go and it’s just a case of choosing which one to start next... page 10 www.brookguitars.com Stories in the Strings “ It would be great to sit back in the audience and watch others perform my works without having to worry about whether my hands were warmed up or if my memory was on the ball... “ West Country musician/composer Stephen Yates is one of select group of Brook customers to have won ‘Guitarist’ magazine’s ‘Acoustic Guitarist of the Year’ title. Steve’s challenging solo guitar pieces are showcased on the 2010 CD ‘Stories in the Strings’, and here, in a wide-ranging interview, he talked to Martin Bell about his music, composing on an ancient Atari computer – and his electric alter-ego, Fieldmarshal Gorsefinger... Photos: Melissa Till MB: When and how did you first start playing? SY: When I was 13, my mother was helping to look after a boy with severe learning difficulties who also owned a cheap plywood guitar, which ended up lying around our house. I would sit with it and mess around, playing bits of music I’d heard here and there, whether it was erstwhile pop songs or attempts at flamenco or ‘Three Blind Mice’. I didn't regard it as ‘learning an instrument’, I was just messing about. After a while, I was allowed to have a go on a Spanish guitar my mother owned. That’s how it all started... loved the sound of the flamenco guitar and my mum picked up a copy of ‘Flamenco Virtuoso’ by Philip John Lee (who sadly died recently), which I listened to incessantly and which gave me my first experience of working stuff out off records. I was also interested in the electric guitar as the older kids in school had bands who’d perform occasionally playing contemporary hits. I remember reading somewhere that in terms of sheer physical complexity, the guitar was the hardest instrument in the world and that was another spur. Who could resist that challenge! MB: Was music always your primary career goal? MB: Who/what were your earliest influences? SY: That year (1973) I do recall hearing Segovia on the radio a couple of times and being very taken by the sound of the classical guitar. On top of that, I’d always SY: In school I flatly refused to study music as I knew it would ruin my enjoyment of the subject just as it had done to every other, but I did after about 18 months continued on page 11 www.brookguitars.com page 11 Stories in the Strings from page 10 submit to my mother’s demands to get a private teacher as I had to admit that by that time my playing had reached quite an advanced level, ( I was already learning classical concert pieces) armed as I was with fullsized photos of Segovia’s hands and ancient tomes by such luminaries as Aguado etc. So I studied with David Stanley in Exeter and subsequently with Douglas Rogers at the London College of Music. Obviously I never had lessons on electric guitar, or in blues playing or banjo, or any of my other stuff, as there were no teachers of those styles then. Sometime around age 16 I guess I started to realise that I wanted to be a full-time guitarist, but I still had to go through the pointless ritual of A levels in subjects I had no interest in by then and couldn’t really give the guitar my undivided attention till I was 18. MB: How do you make your living today? SY: Most of my income is derived from teaching but due to times being as hard as they are I'm actually forced to put on concerts just to earn a little more money. Never let it be said that hardships don't have their benefits. MB: You reached a point in 2005, when – by your own admission –you were ‘forced to accept that classical guitar and me were doomed to part company’. Yet recently, you seem to have returned to it again, rerecording compositions originally composed/performed on the steel-string guitar. Why is that? SY: When I said I had parted company with classical guitar I was thinking primarily about the whole clasiscal repertoire thing. I have no intention of going back to playing programmes entirely made up of other people’s works, although I always throw in a few when playing to ‘non-specialist’ audiences. My main aim was to be a composer performer and I didn’t seem to be able to compose on a Spanish guitar for some reason. Its particular sonority did not inspire ideas. The issue of the instrument is also important, inasmuch as I don’t see why a steel strung guitar cannot be used in this way (i.e. for through-composed pieces). Barrios used steel strings and not always out of necessity either, because when Eclectic electric... FOR all his virtuosity on the acoustic/classical guitar, Steve is equally well-known for his prowess on the electric guitar. He holds regular electric workshops near his Devon home, and has produced an electric guitar ensemble repertoire under the pseudonym ‘FieldMarshall GorseFinger’... the opportunity to switch to gut came he turned it down. It’s true I had no initial intention of performing my works on a nylon string instrument but it became apparent that many of them would actually sound better this way, and ultimately it’s the music that matters. I enjoy the projection and dynamic of a good Spanish guitar and the fact that I don’t need to amplify. I’m not, however, abandoning steel string in any way. It’s just taken me the last nine months to get my pieces to work properly on a Spanish, and all my latest Youtube uploads have been on such an instrument. I must admit, they seem to work well on it! MB: There are few, if any, other guitarists playing such complex music on the steel-string acoustic; did you have to make any technical ‘concessions’ to playing these pieces on the steel-string guitar, or were they originally conceived for the instrument? SY: To date, all my pieces were written on a steel-strung instrument except those that were written on a computer, with no specific sound in mind (eg ‘Mr Hyde's Hop’ and ‘Elegy for a Forgotten Story’). ‘The Girl Who Touched The Sky’ was written on an electric guitar originally, although I perform it on acoustic. I have up to now made few if any concessions to difficulty. I never ever thought I’d perform ‘Mr Hyde's Hop’ because I assumed it to be unplayable on a single guitar. The piece was just written as an abstract piece, and a lot of work went into finding fingerings that would render it playable without altering the notes. My new year’s resolution, however, is to write slightly easier pieces, as the amount of preparation some of my stuff requires is something of a nuisance. Obviously, these pieces are even harder on a nylon string (Spanish) guitar as the neck is a lot thicker and high fret access severely limited. I’ll never be able to play ‘The Girl Who Touched the Sky’ on one, because the high passages can’t be made to sound smooth – at least not by me. MB: Do you usually compose with guitar in hand or do you adopt the view that it's better that technique should expand in order to play new music? SY: Composing on the instrument has two big continued on page 12 MB: Did your electric guitar playing develop in parallel to your classical/acoustic studies? SY: It’s worth remembering that the early 1970s were a period of tremendous musical eclecticism. Electric guitarists such as Jan Akkerman, for instance, thought nothing of including a few renaissance lute solos on their albums, and John Williams was seen playing a Les Paul! As a result, I played both classical and rock and saw nothing odd in so doing. I was also playing bluegrass banjo and masses of blues. In fact, for a while those two areas were where I spent most of my time. I still think I’m a better banjo player than guitarist. MB: Do you regard electric and acoustic as two separate ‘identities’or two halves of the same whole? SY: This is a really interesting question and I could go on all day but I’ll try not to! I’ve always noticed that I can’t practice electric in the morning and classical in the afternoon as when I am enthused with either one I am consumed by it and have no interest in the other. Everything about electric guitar seems almost anathema to a classical sensibility and vice versa. I’d even go as far as to say that my whole personality alters depending on which one I’m immersed in so, yes, they ARE separate identities but it’s not electric which is the odd one out but classical. I’d lump my electric playing self in with my steel string, blues and banjo-playing self, but when I play classical everything alters and was one reason why I have always been uncomfortable as a straight classical player and contributed to why I gave it up. When I play electric, there’s not a whiff of the classical or acoustic about it. I play a bluesy fusion style these days, although I was a hard rock player in my youth. I like plenty of caustic overdrive a la Frank Zappa, although these days I use a Strat. I suppose the player I most admire at present is Guthrie Govan and I tend in that direction but a little less jazzy. www.myspace.com/ fieldmarshallgorsefinger page 12 www.brookguitars.com Stories in the Strings your pieces appear to be very much centred on harmonic/theoretic/ technical concepts – others (particularly a tune like ‘Summers Spent’) possess more melodic romanticism about them, and tell more of a story. Discuss! from page 11 advantages. Firstly, you are able to work directly on the sonorities and textures that will make the music attractive. Music written away from the instrument can often feel awkward in this respect. Much classical guitar repertoire of the last century was written by non guitarists and can suffer in this way. Creating a consistent sonority is vital to guitar music, hence the reason so many players these days use DADGAD. Look at the marvelous sound flamenco players get – they write on the instrument. Secondly, the music is, as a result of these factors, usually a lot easier to perform. On the other hand, writing away from the instrument is a lot quicker. Put a guitar in my hands and the fingers will immediately suggest myriad alternatives to any given phrase resulting in a severe ‘bogging down’ of the creative process. Personally, I can write three or four pieces using my computer to hold each idea as it comes in the time it would take me to get one piece together on the instrument, with all the repetitive faffing that goes with doing it that way. MB: Speaking of computers, I know that you have an old machine to assist you while composing. How does this work? SY: I use a truly antedeluvian Atari 1040 running a programme called Notator, which brings the basic score on the screen and you click your crotchets and quavers on with the mouse. The whole thing is only 2MB and dates from about 1988. I run it into an old Roland JV1080 synth which can, if I want it to, sound like a crude orchestra. My current method of composition is a cunning combination of on the instrument and off with me sitting at the computer with a guitar on my lap. I think of what I want to hear and put the notes in. I then check the phrase on the guitar for playability and sound and make what adjustments are necessary to create a guitaristic effect. This way I don’t have to make modifications once the piece is finished. I’ll then write it out by hand on manuscript and learn it as I would any piece. MB: How do you approach composition? Some of SY: Ultimately, it’s all about having a piece of music in my head that I want to make concrete and doing so, but the process can take several forms. A piece like ‘Io Pan’ has a structural concept that I decided I would stick to come what may and use as a backbone for the melodies, which could then be made to echo each other as a result of this common rhythmic relationship. On the other hand, ‘Elegy for a Forgotten Story’ was an attempt to create a certain sonic effect of slow floating melodies over a rather expansive backdrop. As a rule I find the most important factor is some sort of cohesive structure. Above all the music must feel balanced otherwise no amount of pretty tunes and harmonies will redeem it from sounding awful. I’ve found exceptional delicacy and lightness of tone in Brook guitars – very bright but also sweet and ideally suited to fingerstyle playing... There are times when I may map out whole sections so that I know how long melodic phrases are going to need to be. This is one area where working on the Atari is very helpful. The overall structure is much easier to monitor. I do have concepts in terms of melody and harmony. My first completed solo piece was ‘The Girl Who Touched the Sky’ and that is an exploration of the hexatonic scale using pentatonic in the melody but referring to a sixth note in the bass or internal voices. This inspired me to use this system rather a lot and people might be forgiven for thinking that that is my compositional style but in fact it was just a phase I was going through. My more typical style would be exemplified by either ‘Mr Hyde’s Hop’ or ‘March For A Free Man’, especially the latter with its ambiguous tonality. If you look on Myspace under ‘Music’, for ‘FieldMarshall GorseFinger’ you will hear some of my compositions for electric guitar ensemble. One, entitled ‘Return To the Sky’, is an attempt to use ‘The Girl Who Touched...’ style but enriched by the larger number of notes happening at any one time. ‘Gorilla Tango’ and ‘Zooch Thrust Sprool, Caroline Thrust Zooch’ are highly chromatic and ‘Man Stacks Stone’ was where I first turned on to the hexatonic thing and was actually where I derived many of the chord shapes and ideas for ‘The Girl Who Touched The Sky’. MB: Do you think of yourself as a guitarist who composes your own music - or a composer who just so happens to play guitar? SY: I think if I had more outlet for my non guitar stuff I might start feeling like more of a composer. It would be great to sit back in the audience and watch others perform my works, without having to worry about whether my hands were warmed up or if my memory was on the ball. Hell, I could even have a drink BEFORE the gig! As it happens though I must confess to feeling more of a guitarist who now performs his own stuff although it does make a sizeable difference to how I view performing. When I played standard repertoire it was all about how well I go down as a player.( compared to all the names who have played those works in the past) Now it's also how well the pieces go down. I don't feel I’m being compared to others so much, which is a relief, but on the other hand I have to dish up music no-one’s ever heard before and make them like it. MB: What music do you listen to and what inspires you? My standard answer is that I never listen to music – but that’s not strictly true. I enjoy the folk music of all parts of the world, particularly in its unmodernised forms; the more ‘primitive’ the better. I’m developing a Radio 3 habit at present and I’ve always enjoyed the Russian nationalists, such as Mussorgsky, as well as great quantities of early 20th century stuff like Ravel or Scriabin. I still like the old blues men and recently wrote a number of songs in the style of Charlie Patton, as it’s hard to find continued on page 13 www.brookguitars.com Stories in the Strings page 13 beautiful guitar to look at as well. I used to own a Torridge, but sadly had to part with it some years ago. At that time I wasn’t playing steelstring acoustic and I also wanted a Strat, so it had to go. Shame, as it was a very fine instrument. from page 12 musicians with any commitment down here these have never been performed. I adore Flamenco and keep telling myself to make time to actually play it as it was my first love on the guitar. I do like some popular forms. A lot of 70s prog still inspires me, or a band like Little Feat, and there’s masses of new stuff I enjoy too. I really like electronic music if it’s done well; Aphex Twin, for example, is an artist I’ve been very impressed by. I still enjoy much reggae, especially some of the older stuff like Prince Far I or Augustus Pablo. It has a haunting quality that’s really unique. Two artists in particular have had an impact on me. One is Don Vliet, aka Captain Beefheart, who has inspired me in much of the electric guitar compositions that I’ve done, even if they aren’t actually using similar ideas as such. The other – much more importantly for me, since he’s greatly influenced my compositions – is a man who, strangely enough, was a school friend of Vliet’s, and that is, of course, the late, great Mr Frank Zappa. It was hearing his piece ‘G-Spot Tornado’ that made me realise I could compose as I was able to notate it in my mind whilst hearing it due to the musical language corresponding to the one I had become familiar with through my study of the electric guitar. This served as a window into wider musical systems becoming available to me in the same way as all the myriad bizarre scales I used while improvising became tools for composition. In general I’m not sure if I’ve spoken much about my compositional influences, but I definitely feel an affinity with Ravel and Stravinsky, as well as Mussorgsky, Janacek, Scriabin, Kordaly and Zappa. Progressive rock is also something that permeates what I do, as well as world music and early music. Old Irish harp music, of which very little survives, is a good example of the type of thing I like to play with. MB: What guitarists/musicians do you like/ listen to? SY: I’ve probably had a phase of being ‘into’ pretty much every guitarist I’ve ever heard (well, maybe with a few exceptions). There’s always something to latch onto. One player, though, stands out a mile and that’s Paco de Lucia. He revolutionised flamenco guitar not once, or even twice, but three times! He has produced more crossover sub-genres, new ensemble line-ups and instrumental combinations and general internationalism MB: What qualities have I found in Brooks? than any other musician I can think of – and he’s a guitarist! There’s something we can all be proud of. Others who continue to inspire me include Kazuhito Yamashita; what he did in the 1980s is still unsurpassed and he is in my opinion the one true original thinker in classical guitar of the last 30 years. Guthrie Govan is also someone I am constantly in awe of. What he can’t do on electric isn’t worth doing. I could go on, but there are really too many. As for musicians who are not guitarists: all of them! All the leading classical soloists, singers, jazz saxophonists, Mongolian throat singers, Irish uilleann pipers. Dead or alive, they’re all great... MB: What musical projects do you currently have on the go? SY: At present I just want to build up a respectable body of solo guitar works. I have a mass of musical styles and ideas that I’ve yet to try on the guitar and I’m on the lookout for what might be the best way forward. Only by constant experimentation will I discover what I like to write and to perform, and what will make the most effective guitar music. There are other things I’d like to do as well, but I feel at present that I need to press on with my solo guitar project. I haven’t composed anything in 2012 as a way of refreshing my creative energies, so you can guess what my 2013 New Year’s resolution is... MB: Besides being a fellow Devonian, what led you to Brook guitars? SY: Well, I’ve known Simon (Smidmore) since 1976, so I suppose that is the main reason I knew about Brook – although I wouldn’t buy someone’s guitar if I didn't think it was good, no matter how close a friend they were! I currently play a custom Taw, with a cutaway and a slightly short (63cm) scale. It has a spruce top, Indian rosewood back and sides. It’s rather ‘aristocratic’ sounding, which is in my opinion one of the strengths of Brook’s instruments. Very bright and full of overtones. It’s also a SY: Exceptional delicacy and lightness of tone and feel. Very bright, but also sweet and ideally suited to fingerstyle playing. Bright and full of overtones with an almost porcelain quality, especially in the basses, which gives great clarity and definition. They also make a very wide variety of instruments which obviously increases the likelihood of finding something you like. MB: Do you have any other instruments ‘in the pipeline’? SY: If you refer to me getting another Brook then yes, I am thinking of getting a yew-backed guitar off them some time, as I’ve been exceptionally impressed with their use of yew in guitars and its tonal qualities. In particular, I love the response that a guitar with back and sides of yew gives. It’s so light and easy to play, with a lot of sustain. I feel it gives similar characteristics as found in cypress, which is used for flamenco guitars, but applied to a steel string i.e. lighter and more immediate. I nearly asked them to build me one when I was looking at my current model, but it would have taken time and so I did the ‘bird in the hand’ thing and bought the one I did, but I do still definitely lust somewhat over other people’s yew-backed Brooks – so I suspect it’s only a matter of time before I succumb! www.youtube.com/user/stephenyatesacoustic www.stephenyatesguitaristcomposer.co.uk page 14 www.brookguitars.com “ The ‘art’ is the inspirational bit; the ‘craft’ is the careful working of the initial melody idea, to bring it out and realise its full potential... “ I first met singer-songwriter Phil Bird and his lovely partner, Anna Georghiou, at the summer party at Brook’s workshop in July 2012. It was one of those amazing musical experiences that often strike one totally unexpectedly. I knew I was going to meet some lovely people that weekend, and take part in some wonderful music-making – but the moment I heard Phil’s distinctive voice singing one of his wonderfully authentic narratives, I knew I was hearing someone with a unique gift: the ability not only to weave truly mesmerising stories, but also someone who could pen the most gorgeous melodies and envelop them in a positively orchestral sound of the most intricately picked, harmonically rich textures, all backed up by a beautiful-sounding yew cutaway Tamar. I bought two of Phil’s self-released CDs, and knew that I had to find out more about this fine musician, and share it with fellow readers. Rob Jessep Like the Brook guitars he uses to accompany them, modern-day troubador Phil Bird’s songs are meticulously hand-crafted in the West Country. Here, he discusses with Rob Jessep the art of songwriting, his inspiration and influences – and the general ‘quality’of listening at open mic nights. Photos: Anna Georghiou Bird songs RJ: Phil, how would you describe your music and what you do? PB: I am an independent singer songwriter. My songs often have a narrative quality, inspired by our relationship to history, folklore, mythology, the natural environment and each other, and probably 1,001 crazy experiences that defy rational explanation! continued on page 15 www.brookguitars.com page 15 Bird songs from page 14 RJ: Hearing your guitar style for the first time I was astonished by its intricacy and the orchestral sound you get from your Tamar – who were your influences? PB: I first played guitar in the late 60s. I loved the playing of musicians as diverse as John Fahey, Bert Jansch, The Incredible String Band, Martin Carthy and a whole host of influences from that time. I don’t remember learning much from tablature books, but I can still see myself in my angst ridden teenage bedroom slowing down the speed on the latest 33rpm vinyl to learn the and patterns licks. RJ: Do you still play any tunes by those great players? PB: I remember learning John Fahey’s ‘Sunflower River Blues’ note by note, and many of Bert Jansch’s beautiful songs. Bert was a massive influence on a whole generation of guitarists. You could learn the licks but you couldn’t imitate him; there was very individual soul at work in his playing, and very different to Davey Graham, who was a major influence on him. Stuff that I learned then has influenced me immensely and has become part of what I do, but no, I don’t play any specific tunes from that formative time. Phil with his Brook custom Tamar It’s best to write ideas down as you have them, even if it has to be on a beer mat or a bus ticket. I’ve lost a lot of stuff by being lazy and thinking ‘oh, I’ll write it down later...’ RJ: Do you think that with the immediacy of the internet, and other digital technologies, we are beginning to lose valuable skills such as the ability to learn songs from actually listening to records? PB: Today we are immersed in the digital sea of music and muzac, we are saturated with it and musical culture has become very mix and match. The problem as I see it is that many of the younger players can acquire quite phenomenal technical skills and seem to see this as an end in itself, but sometimes the technical skills seem to hide an emotional vacuity. I had relatively few role models, but what I loved to learn was as much of the heart as the head, immersed inside the music and learning to play it from the inside. Guitarists as musical gunslingers is not what it’s about for me. Some of the most beautiful songs I have heard are pared down; the most technically sophisticated music is not necessarily the most accomplished. Some songs are moving because they have a pared down simplicity, heartfelt, with a transparency of technique. RJ: Your songs seem so perfectly structured and the lyrics so easy and free flowing. What comes first, the words or the music? PB: As a songwriter who runs song-writing workshops I often get to discuss this question. There are as many ways to write a song as there are songwriters. When doodling around on guitar a melody may suggest a mood and words may enter into that; or a particular place, memory, or incident may trigger the wish to write and I bring it to the guitar later. I always keep a song writing diary, I also sketch out musical ideas with tablature and record them on the digi studio, so that I remember them and work on them later. It’s best to write ideas down as soon as you have them, even if it has to be on a beer mat or a bus ticket, I have lost a lot of stuff by being lazy and thinking, “oh, I’ll write it down later.” RJ: So do you have studio at home? PB: Yes, I have a Korg Digital Studio. I use two Sampson large diaphragm mics, one at the lower bout and one at the 12th fret to record the guitar, and I also use a Shure vocal mike. I am having to re-think this, however, as I like to record live with no overdubs and the condensers give a lot of bleed-through from the vocals. I’m not very technically-minded, so I am seeking advice on this at the moment. RJ: Do your melodies come fully formed, or do they require a bit of ‘crafting’? PB: My melodies may have their roots in a love of folk balladry contemporary and traditional, but I guess influences come from everywhere; we are saturated with music and muzak. When I’m playing with chord progressions, a melody comes along and weaves around that. Initially, a melody motif may be a spontaneous expression of mood. Whatever comes as inspiration needs to be shaped into a vessel which supports and carries the song’s narrative and essence. Beautiful melodies come like a gift from who knows where! But song-writing is a craft as well as an art. The art is the inspirational bit, the craft is the careful working of the initial melody idea, to bring it out and realise its full potential. It may be a bit of a cliché but sometimes the really beautiful melodies almost write themselves. RJ: I know when I come up with an idea I like, but isn’t quite fully formed, sometimes the pressure is on to try to make something of it – the ‘crafting’ bit is where the real hard work comes isn’t it? PB: Yes, that’s right. I hope I’m getting better at honing down and editing songs back to their essence. I’ve always been a word hoarder, so editing is hard work. continued on page 16 page 16 www.brookguitars.com Bird songs Phil with two of his Brooks, a custom Tamar and a custom Bovey made from local woods from page 15 timbers; a rosewood Tavy, and a beautiful custom cutaway Tamar with a yew body and extra wide fretboard, which I use as my main gigging instrument. A painter once said something to me which I feel applies equally to music: ‘If you have a precious jewel – your painting – you might find the whole painting gets blocked if you just try to fit all your composing decisions around it. Sometimes, we have to let go of the darling bits, and then the painting breathes again.’ It’s like that with songs: each part is there to support the whole, not just to shine on its own. I have a song box where I put all the lines I like but can’t use in a particular song. At song-writing workshops, I offer them out – if anyone is stuck for an idea, they can use them. It’s a fun exercise and it works well, and gets interesting results. RJ: I’m interested in the Bovey being built of local timbers. Do you feel it is important for luthiers to explore using materials nearer to home? Andy Manson, who is also known for using timbers such as cherry, yew, English walnut, pear and other fruit woods, once wrote about how lute makers would always use home grown local woods. As clichéd as this might sound, do you think this produces a more ‘English-sounding’ guitar? PB: I’m not sure; all tone woods have different qualities, and I guess where they are grown must play a part, so it’s very possible. I wonder what Simon and Andy think about this? RJ: What tunings do you play in and what do you feel about alternate tunings in general? PB: I use what may now be seen as the ‘standard’ alternative standard tuning – DADGAD – also variants of open C and G tunings in, both major and minor modes. On one or two pieces I have come across an interesting tuning by the ‘what happens if...’ method, ‘let’s see how it sounds when I drop the B down a half-tone...’, or stuff like that. I’m not very scientific or methodical about it. I would urge people to check out Woody Mann’s ‘Gig Bag Book of Alternate Tunings’ (Amsco Publications, 1997). I want to find out what it is I don’t know, and what a tuning can teach me... There’s enough there for a lifetime. But I don’t want to become an alt tuning anorak. If the mood or idea you are exploring suggests a tuning then you should use it, but to explore the possibilities of any tuning takes time and effort and lots of listening. Avoid the flash and gimmickry, I say – but I don’t always take my own advice! RJ: As someone who has been exploring Csus2 (CGCGCD) for about 12 months now, I would agree it takes time to fully explore a particular tuning, but when you do, it opens up so many creative possibilities. Is there something you do in particular to explore a new tuning? For example, do you find out where common chords and intervals are, or do you simply allow the tuning to unfold its magic gradually? PB: Yes, I like your idea of gradually unfolding the magic of a tuning. I try to let the unexpected have a voice. I don’t want to superimpose what I already know on a new tuning – I want to find out what it is I don’t know, and what the tuning can teach me. continued on page 17 Tools of the trade RJ: What is it about Brook guitars that draws you towards them as your instrument of choice? PB: I first visited Andy and Simon’s wonderful workshop when I took a Martin HD28 for repair around 1997. What musicians look for in a guitar is very subjective, so all I can say is that I fell in love with the clarity of Brooks’ tone quality across the range of instruments and their astounding level of craftsmanship and design. The elegance, lightness of touch, playability and overall aesthetic feel of the instruments just resonated with me deeply. I had been trying out a number of other makers’ guitars, including Lowdens and Fyldes, and although I had found several good prospective instruments, the Brooks had an extra indefinable sound quality and presence. These are handmade, home-grown guitars with a well-deserved international reputation. So, in the end I sold the Martin, and over the years I’ve come to own several fine Brook instruments. RJ: How many Brooks do you own? PB: The Taw, my first purchase, is a really early instrument that has matured in tone quality over the years, and kept its structural integrity despite the tough time it has probably had with me as an owner! I also have a custom Bovey completely built of local RJ: I know that Brook seem to be making a constant stream of instruments with cherry, yew and English walnut, even recently chestnut from someone’s own garden. To me at least a Brook will always sound like a Brook, no matter what the tonewood, and I remember having a recent conversation with Simon where he was of the opinion that the top has far more influence on the sound than the back and side woods. So, what would be your ultimate Brook (if you don’t already own it)? PB: I guess the simple answer would be ‘the next one’! A while back Simon and Andy invited me to play on a small-bodied 12 string, The Little Silver. I have owned several 12-strings over the years and always ended up selling them, as being too heavy, cumbersome and grim to tune. The Little Silver is different: incredibly light yet robust and it plays with an ease approaching that of a six-string regarding string tension and action. I would definitely like to own one...’deep inside my heart I carry the dream’. Ha ha! RJ: I know of another Brook owner who has written a number of pieces for a 12-string Little Silver, which he described as ‘Sounds like little angels tap-dancing on crystals’. It would certainly make a great songwriting tool. PB: Yes, without a doubt it would be great, I‘ve always found that when I play an unfamiliar instrument, new songs come out. The unfamiliar tends to enchant and stimulate the imagination. Sometimes, no matter how good the instrument, I can fall into a rut with it. New sonorities wake me up – or maybe that’s just an excuse for me to obtain yet another guitar! www.brookguitars.com page 17 Bird songs from page 16 I try all sorts of shapes and fingerings out, the major and minor progressions tend to sort themselves out naturally in the process. But I don’t start deliberately imprinting them. I have doodled around with that wonderful Csus2 tuning you showed me. It’s sheer delight and I hope I will find a song in there sometime. RJ: As someone who has all but convinced himself that he cannot write lyrics how would you approach working with someone like me? Do you actual think anyone can write a song? PB: Yes, I believe that anyone who really wants to can write songs. I have run workshops where really powerful lyrics have emerged from people who thought they couldn’t write. Once we get beyond trying to write how a song should sound, and dig into our own real interests and life experiences, and stuff we really care about, then clichés dissolve and authentic writing begins. One thing that makes workshops so exciting is getting to the end of a session and thinking Woah! I wish I could have thought of that line. Some people on workshops write really great stuff – it keeps me on my mettle. RJ: You recently performed some new, and as yet unrecorded songs at last year’s Brook summer party. They told poignant stories of characters such as tin miners and witches. Are they going to be on your next album? PB: Spirit of place has always been an influence in my work. Here in Okehampton on the edge of Dartmoor I have written several new songs. ‘The Tinner’ came about after several visits to tin workings and mediaeval sites around the awesome vast, sparse moorland of Scorhill. This song is a fictional portrait of a miner working during the times of the harsh stannary laws and iniquitous Lydford jail. ‘The Salmon’ is another recent song inspired by the two Ockment streams which rise on the deep moor, flow through the lush oak wood valleys and join in the heart of the town. Atlantic salmon still return here after many years at sea to breed in the very stream they were born in. In the song I wanted to contrast the seemingly ageless cyclical return of the salmon, with the more fleeting aspects of our human condition. By the salmon run is an old kissing gate leading to what was once a Victorian workhouse, so the song also explores the joy of youth contrasted with the frailties and cruelties of old age. ‘The Witch of Litchfield’ came about after visiting the cathedral city of Lichfield, which has the dubious honour of being the last town in England to burn a heretic at the stake in 1566. The song’s harrowing theme is about hysteria, superstition, and religious persecution during the era of Europe’s infamous witch trials. It’s a tale told through the eyes of the husband of a young wise woman, who is accused of witchcraft and cruelly put to death. All three of these songs will be on the new CD, ‘Gleeman’s Tales’. There are surprisingly very few opportunities for acoustic players to play out to sympathetic, listening audiences... and some folk club singarounds have all the expectant atmosphere of a dentist’s waiting room..! RJ: Can you tell us about the acoustic sessions you run in Okehampton – what sort of turnout do you get? How are they run? PB: We wanted to open an acoustic club, rather than an open mike, of which there are so many; some are very good, but others are more like musicians’ cattle markets, where players are shunted on and off and the music treated as if it were auditory wallpaper – just a background to banter. There are so many good musicians around and they deserve more than that. RJ: This rings very true for me – I recently went to my local folk club, which was having a ‘singaround’ , where we all sat round in a circle and dutifully played our little piece, before moving straight on to the next item. It felt more like a conveyor belt! PB: There are surprisingly very few opportunities for acoustic players to play out to sympathetic, listening audiences. It’s all got very silly. I have sat in open mics where really fine and original acoustic players have had to put up with a constant barrage of banter. Maybe it’s stuffy of me, but I find that so disrespectful, dumbed down and ignorant. Why can’t people just stop babbling and enjoy the wonderful experience of listening? I must be careful not to get on my high horse here, as there are quality open mics, but the general level does make me angry when I see fine music being ignored and some folk club singarounds do have all the expectant atmosphere of a dentists waiting room! It was in response to such dissatisfaction that we decided to start up our own acoustic club, in a community centre rather than pub. We have a cafe style atmosphere with candlelight, people can bring their own drinks- alcohol or non- and we provide a performance platform for 4-5 different acts each monthly session. Each set is about 25 minutes, so performers have a chance to settle in and give a mini concert, and the audience of around 30 to 40 people do come to listen when people are performing. RJ: As an independent musician, what is involved in trying to promote your own work and get your name out there? PB: It is difficult for independent artists to get their work out. Making CDs has been a bit of a home-grown industry for me since the mid-1990s and I’ve produced several albums – ‘Storm Gold’, ‘Little Vessel’, ‘The Famous Flying Bedstead’, Shape the Clay’ – and a poem and narrative album called ‘Snapshot Horizon’. Websites are important, and my partner Anna has just continued on page 20 page 18 www.brookguitars.com The mere thought of going anywhere near a truss rod strikes fear into the hearts of most guitarists. But maintaining your Brook Guitars’Simon Smidmore explains in this simple ‘how to’guide to guitar set-ups... instrument’s playability is a lot easier than you might think – as That’s a relief... EVERY Brook guitar that leaves our workshop at Easterbrook does so having been set up for what we consider to be optimum ‘playability’ – that is to say, it should be possible to play in any position on the fretboard without having to exert an uncomfortable amount of pressure. In general terms, a guitar with a low action is easier to play than one with a high action. A very low action, however, can also reduce the volume of your guitar and, in some cases, affect the intonation. And if the action is too low, the strings may also rattle against the frets, causing that annoying ‘fret buzz’ we’ve all experienced from time to time. This ‘playability’ is down to what is known as the ‘action’ of your guitar – the distance between the top of the frets and the bottom of the strings. Conversely, a guitar with an action that is too high will almost certainly be difficult to play beyond the first few frets – and pretty impossible the higher up the neck you venture. Fine for slide guitarists, perhaps, but a nightmare for the rest of us! We’re all as different as our guitars, with different playing styles, different string gauge preferences etc. Add to that the fact that the wood your guitar is made from is a ‘living’ medium, susceptible to changes in temperature, humidity and a host of other factors, and it’s easy to understand why your guitar’s action/set-up will need periodic/regular maintenance. Think of it as a ’100,000 note’ service and oil change for your guitar… Whilst it’s always best to entrust these set-ups to the skills of an experienced repairperson – or, preferably, the luthiers who made your instrument! – we can appreciate that this won’t always be practical or possible. But with a little practical knowhow, the right tools and a little confidence (!), anyone can make the sort of small, ‘fine tuning’ adjustments to their guitar that can make all the difference to its playability, without fear of causing any irreparable damage. Three necks take shape, two with the channel routed out ready for the truss rod It’s a common misconception to simply think that adjusting the action on your guitar is a case At Brook, we build fine ‘controllability’ into our necks, which allows plenty of scope for adjustment as and when necessary... of EITHER raising/lowering the height of the saddle (the bit slotted into the bridge that the strings rest on!) OR cranking the truss rod in one direction or another. Very often, the correct set-up on your guitar will be achieved by a subtle combination of the two, in greater or lesser degrees – and, in more extreme cases, other remedial action best left to the professionals. But before we get into the ‘how to’ part of the article then, it’s perhaps first best to understand the ‘mechanics’ of what we’re dealing with, and how it all works within the context of your guitar’s set-up’. Sometimes, looking down the neck of your guitar can give the alarming impression of a ‘bow’ or a dip in the neck, when in reality there isn’t really any more than there should be. Neck bow is often talked about in hushed tones, as though it’s one of the worst things that can happen to a guitar. Certain companies, such as Martin, have always built in a certain amount of intentional bow into their necks – although that was in the days when a non-adjustable reinforcing metal bar was embedded inside Martins’ necks. At Brook, we build fine ‘controllability’ into our necks, allowing plenty of scope for adjustment as and when necessary. As part of this short article on setting up your Brook, we thought it might be helpful to show a few photos of the stages of the building process we use at the workshop by way of an explanation. We initially cut the neck blanks from large boards and store them until they’re at the same humidity as the rest of the woods we’ll be using on the guitars. When we’re satisfied the neck blanks are stable we’ll square the top edge along with the top of the headstock and face the headstock with an ebony head veneer (see left). The next stage is to rout a curved channel centrally continued on page 19 www.brookguitars.com page 19 1 That’s a relief... from page 18 along the neck blank and cut and chisel out a housing for the adjustment nut one end. When the body end of the neck has been dovetailed another housing is chiselled out to trap the locked nut which stops the rod turning. 2 Andy cuts to size and threads each end of the stainless steel rod. He makes up a brass nut and washer on his lathe for the adjustment end. We wax the bar to allow it to move in the slot then glue and press wooden fillets tightly over it so the rod follows the curve of the channel. There is a strip of ebony at each end of the fillet to give the nuts and washers something solid to draw up to. 3 After the excess wood from the fillet is removed and the top edge is squared off we fit the dovetail to the body and position the fingerboard with pins before gluing and clamping it. Now we have the truss rod under tension – as you tighten the nut the rod tries to straighten out and we have an ideal means to control the neck when the 150lbs tension of a normal set of guitar strings at pitch is added to the equation. It’s important to understand the truss rod is NOT there to adjust the action – it’s there simply to set the neck relief. The action is adjusted by raising or lowering the saddle... essential that the fingerboard has a small forward bow. Firstly, with the strings tuned to pitch, we check the relief on the neck. An easy way to do this is to put the guitar into the playing position and put one finger behind the first fret and another behind the 12th (see picture, below). Roll the clock on and we have the new guitar on the bench with its first set of strings on and we now want to set the guitar up for optimum playability using the same sequence of processes that you or your luthier will carry out setting up the guitar in the future. The important thing to understand is that the truss rod is NOT there to adjust the action – it’s there simply to set the neck relief. The action is adjusted by raising or lowering the saddle. 4 Checking the relief on the neck is simple and straightforward If the fingerboard is set flat when you fret the guitar, you’ll find you have a lot of unwanted fret rattle behind the point of contact, so it’s We’re looking for a small gap, perhaps the thickness of a business card, between the underside of the sixth string and the top of the sixth fret. Left, from top: 1 – Andy makes up the hexagonal brass nut 2 – He threads both ends of the stainless steel truss rod 3 – Here’s the fixed end of the rod and the housing on a standard neck 4 – Pressing and gluing the fillets on to the rod before the fingerboard goes on If the gap is larger it’s time to tension the truss rod – give it a small clockwise turn with a 1/4” ring spanner. If the fingerboard is too flat and the strings touch the frets, knock the tension off a touch by turning the nut anticlockwise. When the relief is set correctly the action (height of the strings off the frets) can be optimised by raising or lowering the saddle by adding or removing shims. continued on page 20 page 20 www.brookguitars.com Bird songs from page 17 produced a wonderful site for the work we do together now as Troubadour’s Garden. This year, festivals have included Croisant Neuf in Wales, Buddhafield Living Arts gathering, and fringe events, gigs on the acoustic circuit and benefits. Independent and regional TV/radio are very useful when you can get a slot. We also do music and visual arts workshops, often connecting them to our performances in some way. RJ: What music inspires you? I sometimes sense quite a range of subtle influences on your songs – maybe elements of jazz and world music creeping in? PB: Roots, classical, jazz, folk and world, I listen to a wide range of music, often instrumental stuff more than song based work, I try not to be too self conscious about analysing what influences me. If something sounds moving, compelling, beautiful, crazy, mood driven, magical or whatever, it may find its way into what I do consciously or otherwise. RJ: ‘Carry the Dream’ is one of my favourite songs on your latest album ‘Shape the Clay’, with a strikingly beautiful melody, and poignant, thought-provoking lyrics – tell us how you came to write this song. PB: Thank you for liking that song. I wrote it in Cyprus as a sort of positive defiance to all the negativity that assails us, and that we absorb from world events. If, in our personal situations, we allow the large issues to break us down and we lose our dreams of how life could or should be, then we score a home goal. RJ: You work with various other musicians on your albums, including your partner, Anna, on woodwind. It must have been extremely satisfying to have had Steeleye Span bass player Tim Harries play on your ‘Little Vessel For A Long Journey’. Tim gave generously of his time and musical wisdom in playing on the ‘Little Vessel’ album and producing ‘The Famous Flying Bedstead’. He’s a very gracious man. I began a musical learning curve (which I’m still on) by listening to what he had to say and more than anything else by hearing the sheer beauty and economy of his playing. I have always loved the flute playing of Anna Georghiou, who is an international painter as well as a self-taught flute player. She has contributed immeasurably to the musical landscape of my songs. Tim Averik, the Swedish classical violinist, enabled my work to express more emotional depth, on ‘Shape the Clay’. We recorded that CD in Larnaca and played several concerts before he had to return to Sweden. RJ: The title track from ‘Little Vessel’ is unusual in that your are accompanied by just mandolin. Do you play any other instruments? PB: Guitar is my main instrument, I play a little Neapolitan mandolin and a bouzuoki made by John Hathaway. I also have a love of Northern Indian and Carnatic music, especially sitar and sarod. I have played sitar during performances including an Asian world music festival in Nicosia, where Anna and I played with the master tabla player Ravi Sandanker. It blew me away that he asked, as my sitar playing is both elementary and eccentric! I have never played sarod in public; it’s such a difficult instrument, but I love its concise elegant, rich and hypnotic sound. And to hear the work of masters such as Ali Akba Khan and a whole generation of younger players is as good as it gets. RJ: Can you explain what a sarod is? PB: The sarod is a medium-necked lute with a metal fretless fingerboard, with four main strings and 18 sympathetic strings. I think it evolved in the 19th century from an earlier instrument, the rebab, which had wooden neck. It has become a ‘royal’ classical Indian instrument, on a par with the sitar, and it’s really difficult for a guitarist to play, as it requires long nails on the fretting hand to press the strings down. If you play it with short nails it makes a very unsatisfying ‘plinky plonky’ sound. Mohan Bhat plays an adapted guitar with sympathetic strings in a slide-like fashion, which to me has some of the beautiful qualities of the sarod. Listen to ‘Meeting by the River’, a very beautiful improvised musical encounter between Mohan Bhat and Ry Cooder, or any of the sitar/sarod duets between Ravi Shankar and Akba Khan, or the younger generation of players on the Sense World Music label. RJ: Where can we hear you play, and how can we buy your CDs? PB: As Troubadour’s Garden, we’re in process of organising touring dates, and also look out for us on the acoustic circuit, festivals, village halls and Art Centres, etc. Each month we play a set at our own club, Okehampton Acoustic. Check us out on www.troubadoursgarden.wix.com/music and www.okehamptonacousticclub.moonfruit.com And thank you, Rob, and Brook Guitars for giving me the chance to stretch my few remaining brain cells to attempt to answer these questions... A small turn clockwise or anticlockwise with the 1/4” spanner will adjust the tension on your guitar’s truss rod That’s a relief... from page 19 The only other item for consideration in the nut height – well, the height at which the strings leave the nut slots. The slots have to be cut as low as possible to avoid having to stretch the strings in the lower positions; however, if these are too low the strings will rattle on the frets. We cut these slots very carefully before the guitar leaves the workshop so it shouldn’t be a problem. But if work needs doing to the nut, it’s really a job for the professional and you should let either us or another competent luthier look at it. And that’s pretty much it for a simplified instruction on the set-up! There are, of course, an awful lot of subtleties that it’s not necessary to go into at this stage, but for the moment all you have to remember is the simple rule: use the truss rod to set the relief, then adjust the action by raising or lowering the saddle.