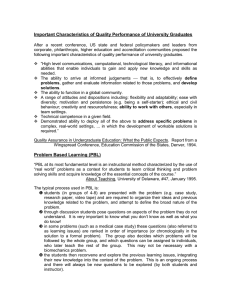

annexure a - University of the Witwatersrand

advertisement