Enhancing facilitation skills through a practice development

SCHOLARLY PAPER

Enhancing facilitation skills through a practice development Masterclass: the other side of the rainbow

AUTHORS

Sally Hardy

Professor of Mental Health and Practice Innovation, City

University London; Adjunct Professor, Monash University

Melbourne Australia; Visiting Professor, Canterbury and

Christchurch University England; Honorary Professor of

Nursing, University College Hospital, London.

Sally.Hardy.1@city.ac.uk

Danielle Bolster

Director of Nursing Workforce Development, The Alfred

Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Teresa Kelly

Formally at the Centre of Psychiatric Nursing, Melbourne

University, Victoria, Australia.

Joan Yalden

Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

With significant contributions from

Jackie Williams, Katrina Lewis, Heidi Bulda, Shirley

Burke, Gwenda Peters, Sally Hicks, Stephen Abbott and

Professor Brendan McCormack.

KEY WORDS

Facilitation, practice development, co‑operative inquiry, (individual, team and organisational) transformation

ABSTRACT

Objective

Professional impact and practice based outcomes of an inaugural Practice Development Facilitation Masterclass, for facilitators of Practice Development activity in Victoria, Australia, is presented. The Masterclass educational program format is designed to incorporate experiential learning strategies with individual transformation as an explicit goal. The program structure is underpinned by critical social science and delivered through a co‑ operative inquiry approach. Evidence of personal and professional transformation, identified as a consequence of participation in the Masterclass is reviewed, as we aim to share the ‘other side of the rainbow’, as a symbol of participant’s transformation during the Practice Development Facilitation Masterclass experience.

Primary argument

Skilled facilitation is a key requirement in modern health care, as practitioners are expected to innovate within a changing and complex workplace environment.

Conclusion

Using a Practice Development facilitation Masterclass program format as outlined, provides a structured experiential educational program that could enhance and enable many professional teams to understand and facilitate effective health care practice. Engaging in a co‑operative inquiry process provides a supportive yet challenging learning culture for sustaining individual and team’s professional development.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

36

SCHOLARLY PAPER

INTRODUCTION

Global health care is continually being challenged to implement change strategies that can embed new technologies, deliver outstanding, high quality, safe and effective care delivery from a workforce that remains fit for purpose. Such high level demand can lead to a direct confrontation for health care practitioners, who are continuously faced with a myriad of competing demands on their knowledge, skill and practice expertise.

Bevan (2010) asks what skills are required in order to sustain the healthcare workforce’s energy for such a rapid pace of change, enabling them to deal with work place complexity, whilst at the same time promoting and maintaining effective service delivery alongside economic sustainability? According to Pierce, et al

(2000) it is the more progressive organisations that look to a participatory approach for long term solutions for sustainable organisational advancement. The aim of this paper is to consider how transformational intent, delivered through a Practice Development facilitation Masterclass programme’, was able to provide a platform for improved facilitation of effective workforce development. Insight into participants’ expressed personal and professional advancement are revealed through an evaluation of the Masterclass experience.

Transformation is seen to be achieved through an increased ability for facilitators to work with confidence to sustain and lead practice based health care innovations.

Transforming individuals and groups has been a fascination within many fields of study (e.g. psychology, sociology, and politics), each producing theories to further understand and apply their field of learning to particular practice improvements. Yet information, whether theoretical frameworks or implementation models and change management tools, all require expert navigation to enable busy clinicians to effectively apply learning into practice improvements rather than continue to follow established practices encountered within daily workplace (Kitson et al 1998). Providing effective education for skilled facilitators, (i.e. those expert navigators who can enable practitioners to implement health care modernisation) is in itself a commitment that some would argue, represents an unnecessary additional level of training expense. Yet, we propose it is these skilled facilitators that are potentially the key to achieving organisational goals and sustainable widespread cultural reform.

FACILITATION OF PRACTICE IMPROVEMENT

Practice Development (PD), as a term relating to health care practice improvements, is utilised within the published literature and in practice settings in a variety of ways. PD’s aim is to facilitate the achievement of person‑centred and effective care delivery, achieved through collaborative and inclusive processes that enable all participants to develop their full potential. PD takes into consideration attributes and enabling factors of the workplace environment, alongside consideration of the very practical issues around how daily clinical service delivery can be enhanced, in order to provide safe, effective health care. In reality some PD projects are often time‑limited, involve and depend upon a number of committed clinical staff who led the work within a small localised section of an organisation. However, more recent PD project outcomes have shown how to maximise the impact of working with PD approaches at strategic organisational level, developing transformational workplace cultures in and across whole organisations (Manley 2004; Manley et al 2009;

Manley et al 2011; Crisp and Wilson 2011). In order to achieve a level of sustainability requires highly skilled and effective facilitators (Gerrish 2004; RCN 2006). The development of a Practice Development Facilitation

Masterclass was therefore devised in order to support and prepare PD project facilitators, and their colleagues, with the skills required to deliver on the transformational improvement strategic agenda.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

37

SCHOLARLY PAPER

A working definition of transformational PD

Th e following definition of PD has been developed by the International Practice Development Collaborative, specifically to capture contemporary understanding of PD, gathered through identifying theoretical influences, collective practical experiences of working with PD and strengthening methodological advancement. For example, contemporary understanding of PD includes consideration and explicit reference to the transformative processes that characterises PD’s emancipatory intent (cf. Titchen and Manley 2006) including the notion of critical creativity (McCormack and Titchen 2006). A working definition for PD was used to provide context for the PD Facilitation Master class (PDFM).

“Practice development is a continuous process of developing person‑centred cultures. It is enabled by facilitators who authentically engage with individuals and teams to blend personal qualities and creative imagination with practice skills and practice wisdom. The learning that occurs brings about transformations of individual and team practices. This is sustained by embedding both processes and outcomes in corporate strategy.” (Manley et al 2008:9)

This paper has been developed from experiences and evaluation data emergent from an inaugural PDFM held in Victoria and South Australia (Hardy & Bolster, 2008). Prior participants of PD Masterclasses of this kind (held in England, Northern Ireland and New South Wales, Australia), all confirm the learning experience of the PDFM program as transformational. This paper aims to discover how this transformation takes place, through consideration of the PDFM objectives and the impact of associated theoretical influences used to inform transformational PD methods.

PDFM: program objectives

The PDFM curricula was originally devised by Professor Brendan McCormack and aims to further enhance and support facilitation skills of health care practitioners, particularly those working within identified PD roles. PD roles first started to appear within health care organisations in England during the late 1980’s.

These roles then spread through Europe, reaching New South Wales, Australia in the 1990’s and continues to have precedence in international organisations that identify a need to transform organisational culture and influence practitioners’ ongoing clinical skill development in order to improve patient experience and health care outcomes (cf. Essence of Care Programme, NSW).

The PDFM outlined here was the first in Victoria, prepared and delivered in response to increasing demand for skilled PD facilitators able to lead and support individual practitioners and their clinical teams through organisational wide strategic modernisation programs, being implemented through the use of PD processes and methods. The implementation of the PDFM was therefore in response to several health care organisations’ interest in the development of effective workplace cultures; for example, in areas of clinical practice development, targeted workforce education programs, evidence based practice and increased practitioner led research participation.

The ultimate aim of any PDFM is to expand participants’ knowledge and skills within a cooperative, critical creative and reflexive educational space that can further enable and maximise individual and group learning.

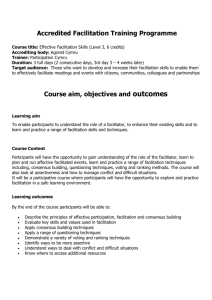

Using a cooperative inquiry approach (outlined in more detail below), the program was tailored to meet the identified learning needs of all participants to promote the development of advanced facilitation skills, enhanced theoretical understanding and professional practice knowledge. PDFM course objectives were finalised with participants in a preliminary example of modelling how to work within a cooperative inquiry approach. Course objectives are displayed in box 1 below.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

38

SCHOLARLY PAPER

Box 1: PDFM 2008 objectives

1. Engage in activities that extend the scope of facilitation practice;

2. Critically engage with facilitation theory and approaches, and distinguish significant differences between models of facilitation and their translation into activities such as clinical supervision, action learning, work based learning, and PD; and

3. Engage in evaluation of individual effectiveness as a facilitator.

PDFM methodology: embedded learning through cooperative inquiry

Cooperative inquiry is a model of action research conceptualised in the work of Heron (1996). Located within critical social sciences, cooperative inquiry shares core values with PD, which embraces holistic, critical, creative, developmental, emancipatory and adult learning approaches that promote and enable a transformation of thought, language patterns and practices that occur at an individual level, moving out into wider social influences

(Friere 1972; Fay 1982; McCormack and Titchen 2006). Cooperative inquiry values individual intellect and practical capacity to participate in the co‑generation of knowledge and skill enhancement, through insights gained by working alongside others, drawing on multiple sources of knowledge, including (within the PDFM context) embodied knowledge of health care practitioners (Reason and Bradbury 2001; Greenwood and Levin

2007). Consistent with emancipation, cooperative inquiry uses methods that openly engage individuals in critical reflection on their learning through practical experience, use of interactive and creative modes of learning, all used in equal measure with emphasis on ‘whole person’ learning (Dewing 2008).

Using a cooperative inquiry approach to program delivery offered the PDFM a framework for identifying and working closely with participants’ shared values and beliefs about how clinical practice is delivered. Participants were invited to engage emotionally, cognitively and practically in determining the direction, structure, evaluation and decision‑making processes of the PDFM program content. Heron and Reason (2001) state cooperative inquiry is about working with people, to help them make sense of their world, using creative ways of looking at things differently; learning how to act to change things a person wants to change and to explore how to do things better. The PDFM was established to maximise potential for participants to achieve personal and professional developmental objectives in harmony with achieving demands arising from strategic organisational goals for improved workplace practices and cultures of effectiveness.

PDFM: evaluation approach

In an attempt to capture and further articulate the process of transformation, participants were engaged in a process of collaborative evaluation using PRAXIS evaluation (Wilson et al 2008). PRAXIS evaluation is an approach that aims to ensure evaluation is undertaken in a manner that reflects and incorporates the principles of transformational PD (i.e. participation, collaboration and inclusion). The six core components of PRAXIS are; p urpose, r eflexivity, a pproaches, conte x t, i ntent and s takeholders. These six elements work together in a ‘praxis spiral’, interlinking evidence with experience, and knowledge development with practical impact; utilising all strands of evidence for evaluation data as they arise and, as a result of, critical reflexion. Reflecting and reframing each element of the PDFM became an integral element for mapping and critically exploring the extent of individual’s learning, without which this deep level of scrutiny was at risk of being hidden, overlooked and not articulated. Participants were able to adapt to the challenge of engaging in regularly offering critically constructive feedback to each other; challenging each step of the program and each other’s participation within it, through discussing and seeking how individuals and the group as a collective contributions were aiding or inhibiting knowledge development, utilisation and transfer (Hardy et al 2011).

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

39

SCHOLARLY PAPER

Using PRAXIS evaluation in this way further helped the group to recognise; a) an inherent ability to evaluate; not only evaluating each other’s level of participation but also how to further scrutinise the impact and outcomes of individual and collective activity. b) consideration of the relational aspects of learning; through critical observation and constructive feedback on all aspects of the program, processes and its impact on group dynamics (cf. Bion 1961). In addition, participants were able to consider how they might wish to use the PRAXIS evaluation framework as a tool to guide, develop and strengthen collaborative PD activities taking place outside of the PDFM sessions, back in their own places of work.

PDFM (2008) participants

Twelve participants attended the PDFM (2008), representing a range of health and education organisational establishments across Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Participants all worked with the concepts and tools of

PD, either in clinical settings or in educational roles. A small number of participants were working in strategic organisational PD roles as well as actively engaging in PD activities external to their organisation. Differing levels of participant knowledge, skill and experience in relation to facilitation and PD theory, was openly discussed and explored as participants began to learn more about each other.

Participants were required to meet for a full day, once a month over six months. All obtained organisational support prior to attending which provided opportunity to ensure PDFM activities were then linked back into strategic organisational goals plus an acknowledged requirement to report back learning and experience, through for example sharing practices taking place in each other’s organisations.

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

In order to provide and expose participants to a rich variety of experiential learning opportunities, sessions were not formally ‘taught’, but led by different participants; each taking it in turn to prepare and test their personal facilitation skill development through leading sessions. The content and teaching approaches for each session were influenced by individual lead facilitator’s teaching styles and consideration of what would suit participants’ learning requirements. For example, when new information was being shared more formal presentation styles were used, whilst other more creative means of exploring participants’ propositional knowledge base were widely employed. Visualisation (cf. Eppler 2006), creative artwork (cf. Bartol 1986) and dramatisation (cf. Yaffe 1989) were used within sessions to embrace the groups learning needs, and to further challenge all aspects of an individual’s person (Heron 2002). This willingness to embrace unstructured activity meant lead facilitators needed to timetable in adequate space for each participant to engage in critical reflection and then to verbalise their considered critical analysis of activities through constructive feedback; experiences and insights (cf. Johns and Freshwater 2005) were articulated at certain key points in sessions, with participants also encouraged to maintain reflective journals outside of sessions.

Attention was paid to identifying and recognising how to integrate key theoretical influences into practical and experiential work being undertaken, to further verify or challenge each aspect of the session for evidence of impact and transformational outcome. As a result, each facilitator individualised their session approach, each choosing different teaching methods and learning tools. This in turn allowed for personalised constructive feedback offered directly from session participants to those individuals leading the session. Each session was therefore constructed as consistent with a cooperative inquiry approach. Active inclusion of participants in their learning was emphasised, through engaging in receiving direct feedback on their contribution, whether they were the lead facilitator or as a session participant.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

40

SCHOLARLY PAPER

Experiential elements included heated debate and lively discussion, alongside quieter times spent in personal critical reflection. The use of role play and creative methods, to promote an environment of exploration and enlightenment, were used throughout the six sessions. None of these processes were entered into by participants easily, or without element of hesitation. Many participants expressed feeling more comfortable with traditional notions of classroom based learning (i.e. pedagogy as a form of instruction giving). The first

PDFM session was undertaken by the PDFM lead, with the intention of providing a role modelling process for the potential scope of a session format. At the request of participants, the second session was again conducted by the PDFM lead for the purpose of specifically clarifying participant’s expectations and ground rules for enabling an open forum of critical pedagogy, that enabled participants to become accepting of each other’s values (i.e. to challenge within a framework of high support and an explicit intention for individual development and increased self‑awareness) (cf. Daloz 1999; McLaren and Leonard 2001). Table 1 below summarises the PDFM six session’s content theme, focus and goals.

Table 1: The PDFM sessions: theme and focus

Session Theme

1 Establishing collaborative principles, program relationships, cooperative inquiry

2

3

Facilitation methodologies – a person‑centred approach

Working collaboratively

4

5

6

Developing cultures of effectiveness

Learning strategies in PD

Evaluation

Focus

Co‑operative inquiry, terms of engagement, data for evaluation, underpinning values, RCN facilitation standards

Exploration of different facilitation models. Exploration of key roles, skills and styles. Evaluation.

Agreeing ethical processes. Stakeholder analysis and involvement. Values clarification. Developing a shared vision. Developing a shared ownership. Celebrating success.

Evaluation.

Workplace cultural analysis. Facilitating cultural development.

Evaluation.

Giving space for ideas. High challenge/high support.

Feedback. Critical reflexivity. Evaluation.

Evaluation approaches. Tools for evaluation. Final program evaluation.

EVALUATION DATA

At the start of the program (i.e. session 1), in order to clarify expectation and approaches to data gathering, in addition to an opportunity for participants to become more familiar with using PRAXIS Evaluation, three evaluation questions were devised.

How has the PDF Masterclass been able to provide: i) an opportunity to learn more about: own facilitation style, develop and practice new skills, gain insights based on different styles and opportunities for learning, and a sound theoretical basis? ii) a safe and trusting environment where new ways of working can be explored and avenues for personal growth/capacity as a PD facilitator? iii) opportunity for sharing and using different methods and approaches, materials and resources to enhance learning and improve confidence to work with PD through to attaining the vision?

In the final (sixth) session, these questions were reviewed again using PRAXIS evaluation. Participants identified a missing element within the original evaluation questions regarding the broader influence of the

PDFM for themselves, their organisations and for other PD activity taking place across Victoria. The following three questions were added to guide and inform the closing phase of the evaluation:

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

41

SCHOLARLY PAPER

1. How has the Masterclass prepared participants to create opportunities for sustainable and strategic directions for PD in Victoria?

2. How has participation in the Masterclass enabled participants to share learning, utilise facilitation and apply new skills in and beyond daily practice?

3. How are the Masterclass participants working together?

The last session utilised a process of guided visualisation, described and outlined as a journey of discovery.

This process aimed to help participants re‑engage with evaluation data collected throughout the program and collated at the close of each session. Each participant responded individually to the six co‑constructed evaluation questions. The group then agreed to further collate these individual responses to form overarching themes, generated using a thematic analysis approach (cf. Wilson and Hutchinson 1991).

In total, fourteen themes were identified, further clustered into three concept domains of attributes, enabling factors and outcomes.

The domains (identified in box 2 below) are represented in bold type and themes are underlined. In addition some of the participants’ individual responses are reproduced (as exemplars to theme identification) and identified in italics. As a point of clarification, from the representative material provided in box 2, ‘enabling factor’ appears as a theme in the domain of the same title. This was explained as enabling factors being both a an important process as well as being considered a core facilitation skill.

Box 2: Evaluation data PDFM (2008)

Attributes

Personal and group attributes.

Person‑centeredness (as a lived way of thinking). Trust. Respect. Holistic.

Enabling Factors

Feedback. Critique – high levels of critique and support.

High challenge/high support. Willingness to take risks and receive support.

Open to feedback and personal challenge.

Collaboration/connectedness. Sharing tools, approaches, using Masterclass as a testing ground. Collaboration with one another outside of the Masterclass. Establishing networks.

Reflection . Reflective practice – within and outside Master class.

Participation . Active participation. Engagement. Being part of planning and facilitating a session.

Commitment . Committing to the 6 months.

Adaptability.

The Masterclasses have been fluid and adapted to time constraints, likewise PD in practice needs to be fluid and adapt and become part of it all.

Creativity . Variety of approaches. Washing machines. Roller coasters.

Creativity in how sessions delivered.

Enabling factors. Ways of working – established early. Lived. Engagement with expertise.

Outcomes

Confidence . I came with a donkey and left with a unicorn. By believing in myself.

Application of learning/opportunities created. Created opportunities in a safe environment. Applying and linking theory.

Development of theory and skill related to PD. Knowledge development and transfer. Developing the skills to enable the support and development of others.

Consequences. Has allowed me to take risks in a supported environment – transferred to workplace.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

42

SCHOLARLY PAPER

EXPLORING OUTCOMES: DISCOVERING TRANSFORMATION

The first evaluation question identified by participants was; how had the Masterclass prepared participants to work with PD? In response to this, participants were able to identify a level of self‑improvement in their skill development and theoretical knowledge, both in relation to facilitation of PD and through application of this learning in complex clinical practice settings. The enabling factors (as described above in the evaluation data), identified the processes and structures within the facilitation program that were noted as directly contributing to positive outcomes for participants. These included experiencing the process of developing and sustaining a learning environment of high challenge, balanced with high support; giving and receiving of critical developmental feedback; use and engagement with creativity in a way that promoted critical reflexion and, new insight at individual and group level transformational learning.

Improved confidence

A large number of participants (75%) commented on how engaging in the PDFM had contributed to improvement in their personal confidence in relation to undertaking and leading on PD work. Participants spoke of knowledge enhancement to building and understanding the theoretical basis of PD that further assisted their ability to synthesise new knowledge that, in turn, could then be more readily articulated and shared with others. Importantly a number of participants also commented on how their knowledge and skill development was becoming ‘embodied’ as a recognised change observed in their daily practice. Change was evidenced through undertaking new critically informed ways of working, not just an espoused improved understanding that did not impact directly on actions, but in practical, action and behavioural changes. The application of new learning ranged from participants’ engaging in activity outside of the PDFM that they and colleagues could recognise as ‘enhanced’. For example, seen through an internally felt gestalt and externally observed increased level of confidence when working with groups. Examples of these practice changes were facilitating action learning in the workplace; developing and implementing locally delivered facilitation development programs and in leading and facilitating team based seminars. Perhaps most surprising to participants was recognition within their organisation of the need for PD to be included at a strategic planning level, rather than used as a means to trouble shoot in problematic areas, which had been participants’ previous experience of their PD role from senior managers. One outcome that signified participants increased self‑confidence was that six (50%) participants took up lead facilitator roles in the International Practice Development five day

School, (held biannually in Melbourne), which brought together a variety of practitioners and educators from across New South Wales, Adelaide and Tasmania, all interested in developing an understanding of Practice

Development.

Collaborative networking

Another theme of PDFM transformative impact was identified as relating to ‘connection and collaboration’, best seen in the established connection formed between participants of the PDFM (and in response to initial evaluation questions 2 and 3). This level of connection also extended into their home organisations, as role and contribution potential began to reveal itself. For example, participants emphasised the supportive value gained from forming established and legitimate networks within and amongst each other, all working in similar roles. This supportive network was further emphasised through the ability to share problematic workplace experiences and use different developmental tools to work through solutions. A shared sense of purpose was also evidence through participants experiencing the impact and effect of being exposing to non‑conventional and varied approaches to learning that they could then use in practice knowing exactly how being introduced to new situations and approaches might make others react and respond. This supportive network was further enhanced through participants knowing they could have the opportunity to call upon each other in various ways outside the PDFM to undertake collaborative work in the future.

Broadening the influence of PD work, identified in the second set of evaluation questions, was fulfilled through the PDFM participants being asked to present their experiences at a national conference. Participants chose to undertake an oral presentation using an image that emerged frequently during the PDFM. This image

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

43

SCHOLARLY PAPER first came to the surface during the creation of a ‘facilitation collage’ in session 4. The poem captured in box 3 below was developed by participants to build upon the repetitive use of a waterfall, as visual imagery, representing and helping to explain the turbulent process of facilitation and a transformational journey of discovery.

Box 3: A waterfall: experience of the Victoria based PD Masterclass 2008

A WATERFALL

“Still waters representing where we all were at the start.

Leaping off… into the unknown – taking risks, jumping in.

The journey down… hitting rocks, energy, and rush of adrenaline still there.

Trying out tools and approaches... falling still.

More tools for the journey, seeing the effect on self and others... sharing, nourishing, challenging.

Tears, reality, clinical chaos, PD calm creativity...

Evaluation rainbow, pulling all the particles together.

Basking at the calm waters at the base.

Where next along the river?

Embracing creativity

The process of engaging with creativity within the PDFM was identified as a shared theme in the evaluation data. This was further explored in evaluation descriptors of a ‘washing machine’ and ‘roller coaster’. Both provide for strong imagery that gives expression to and captures the group’s experiences of emotional highs and lows, thoughts spinning, energetic turbulence and the exhilaration of new insights. Imagery is further used to explore the relationship of the three identified domains to each other and represented in the conceptual image of a waterfall and refracted rainbow.

The imagery of a waterfall and rainbow represent for the participants the dynamic and colourful nature of both a collective and individual process of experiential learning that had taken place during the PDFM.

The process of transformation, as experienced by participants, was accepted and celebrated. Evidence of a recognised alteration in knowledge and skills was able to be clearly related back to the evaluation data; captured in themes of attributes, enabling factors, and outcomes. The attributes of a skilled facilitator was described as ‘someone who can enable others to take a ‘leap into the water’ towards workplace and personal transformation’. This was recognised as a significant starting point to commencing a ‘turbulent journey of discovery’. The group identified how individuals need to be adequately prepared and enabled to ‘navigate the raging waters of workplace transformation’, and not be afraid to ‘bump against rocks’, or undertake some

‘frantic splashing about’, as this activity in itself could further promote expected and unexpected outcomes of transformation. More specifically, outcome was seen and expressed in the formation of a rainbow; a representation of both process and outcome of transformation.

DISCUSSION

Shaw et al (2008) discuss how facilitation is in itself multifaceted and remains largely unexplored in terms of how specialised PD facilitation needs to be over and above any other means of enabling best practice performance. The PDFM approach appears to provide a robust engaging and enlightening process that pulls together both individual and collective contributions, via expressed, experienced and articulated evaluation evidence, of how effective a participatory/cooperative inquiry, critical creative process can be in enabling transformation to occur for individuals and groups.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

44

SCHOLARLY PAPER

What enabled transformation?

The process of utilising experiential adult learning principles, participation and exploration within a safe but challenging learning environment, produced both high level anxiety ( roller coaster ) counterbalanced with exhilaration arising from achieved new insights (both theoretical and practical) and resultant improved confidence; evidenced through externally confirmed changes in individuals critically informed practice (i.e. praxis). One PDFM participant stated; ‘ I came with a donkey but left with a unicorn’. This phrase provides an example of the creative, descriptive imagery participants were beginning to use to expose and explore the subtlety of internal learning taking place for an individual, seen further in how the group changed how they talked and behaved with each other over time, as in itself a process of transformation. Perhaps participants did not see or recognise fully how they themselves had altered but they achieved a greater level of appreciation and understanding of how the different learning tools and approaches, made available to them during the

PDFM, had enabled them to more clearly recognise and articulate how meaningful learning had been at first quite a clumsy activity (i.e donkey), but moved to become more sophisticated and elegant (i.e. unicorn).

According to Barnhart (1988) the word facilitation comes from middle French, ‘ facile ’ and the Latin ‘ facilis ’ which means ‘to make easy to do: of a person courteous’. However, from the emergent data of the PDFM, facilitation of PD is not something that comes easily to ‘persons courteous’; rather the development of facilitation skills requires considerable effort, commitment and a willingness to take risks. Risks associated in establishing personal attributes and amassing the enabling factors needed to produce desired transformational outcomes are largely debated as attempting to achieve a state of utopia that can never be fully attained. Davies et al,

(2000) warns that any organisation aiming to transform its practices requires transparent goals that provide a clear pathway to achievement. The risk is that the destination is never fully attained due to an ongoing state of flux health care organisations find themselves having to manage. A final word of warning is to consider that engaging in a process of transformation does require a level of disruption and disturbance to normative cultures, which can increase individual and collective sense of turbulence and entering unsettled waters.

As Hogan (2002) identified, facilitators work to help staff come together and make sense of their complex, turbulent worlds. Skilled facilitators are able to draw from and effectively use a variety of applied processes, choosing which is more pertinent to localised need and requirements. This ability was replicated in the PDFM delivery mode, where participants agreed to engage in the planning of sessions, then lead these sessions drawing on a variety of tools and approaches, identified by taking into consideration how best to tailor activities to suit participants’ learning needs. Through the gathering of evaluation data and constructive feedback on process and impact of these choices was considered in a hermeneutic cyclical process of critical review and refinement. Participants were not only exposed to their own learning needs, but engaged and reviewed how to best adapt and apply different learning styles and modes of delivery to address other participants needs. Shaw et al (2006) conclude that ‘enabling’ is in itself, a form of expert facilitation, and can only be fully acquired and synthesised through a continuous commitment to achieving transformation of others.

What enabled transformation then to occur in the PDFM, was perhaps the opportunity participants had to experience processes that enabled an exposing, critiquing and testing of individual and collective understanding.

Embracing a model of skill development (such as the PDFM) provided an unprecedented opportunity to test ideas, make new discoveries and further refine these in a supportive collective approach; all leading towards a transformational intent for improved understanding and validation of knowledge, action and resultant outcomes. We recognise however, this is a small and select sample of PD facilitators, undertaking a specialist educational program, and that transferability of findings requires additional investigation on a broader more inclusive sample.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

45

SCHOLARLY PAPER

CONCLUSION

The PDFM aimed to provide an environment that could enable participants to achieve personal and professional outcomes in harmony with strategic organisational goals of improved workplace practices and cultures of effectiveness. Cooperative inquiry offered the PDFM a transformational framework, through working with explicit shared values and beliefs amongst those who participated. Each participant, through a process of PRAXIS evaluation, recognised an increased level in their personal knowledge base from starting the program to its closure. Individuals gathered evidence of their personal skill development and began to recognise altered practices. This was also reported by external colleagues who saw changes in participants facilitation skills, attitude and confidence levels back in the workplace. All of this evidence, gathered from within and outside the PDFM group itself, had helped expose an inherent process of transformation.

Participants expressed the emotional highs and lows of working experientially, yet recognised the impact the experience of exploration, critical reflexion and constructive feedback had on their personal and professional identity.

Further work is needed to capture long term change, as a result of Practice Development facilitation. Greater exploration of what constitutes particular skills and enabling factors required to enable PD facilitation expertise is also required; particularly as quality improvement programs and modernisation of health care facilities continues apace on a global scale. This paper has identified a mere drop in the ocean of what potential can be found in the collation of evidence a transformational Practice Development approach is having on health care practice. We believe PD offers an effective mechanism for navigating the turbulent waters of workplace culture. If expertly navigated the health care workforce can be supported to continue to transform to meet the changing and challenging needs of global health.

REFERENCES

Barnhart, R.K. 1988. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. HM Wilson: Company New York

Bartol, G.M. 1986. Using the humanities in nurse education. Nurse Educator, 11(1):21‑23.

Crisp, J. and Wilson, V. 2011. How do facilitators of practice development gain the expertise required to support vital transformation of practice and workplace cultures? Nurse Education Practice, 11(3):173‑8

Daloz, L.A. 1999. Mentor: guiding the journey of adult learners.

Jossey‑Bass: San Francisco.

Dewing, J. 2008. Becoming and being active learners and creating active learning workplaces: the value of active learning in practice development. In Manley, K., McCormack, B., Wilson, V. (Eds.). International Practice Development in Nursing and Healthcare. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing.

Eppler, M.J. 2006. A comparison between concept maps, mind maps, conceptual diagrams, and visual metaphors as complementary tools for knowledge construction and sharing.

Information Visualisation, (5):202‑210.

Friere, P. 1972. Pedagogy of the oppressed.

Herder and Herder: New York.

Fay, B. 1987. Critical social science, Liberation and its limits. Polity: Cambridge.

Gerrish, K. 2004. Promoting evidence based practice: an organisational approach. Journal of Nursing Management, 12(2):114‑123.

Greenwood, D., and Levin, M. 2007. Introduction to Action Research.

(2 nd Ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Hardy,S. Wilson, V. and Brown, B. 2011. Exploring the utility of PRAXIS evaluation: a tool for all seasons?

International Practice

Development Journal , 1(2):2.

Heron, J. 1996. Co‑operative Inquiry: Research into the human condition. London: Sage.

Heron, J. and Reason, P. 2001. The Practice of co‑operative inquiry: research with people rather than on people.

Chapter 16 in Reason,

P and Bradbury H (eds) Handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. Sage: London.

Kitson, A. Harvey, G. and McCormack, B. 1998. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework.

Quality Health Care, 7:149‑158

Kolb, D.A. 1986. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development.

Prentice Hall: NJ.

Manley, K. 2004. Transformational Culture. A culture of effectiveness. In: McCormack B, Manley K, Garbett R (eds.) Practice Development in Nursing. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

46

SCHOLARLY PAPER

Manley, K., McCormack, B., and Wilson, V. 2008. International Practice Development in Nursing and Healthcare.

Oxford: Blackwell

Publishing.

Manley, K. McCormack, B. 2004. Practice development. Purpose, Methodology, Facilitation and Evaluation. In: McCormack B, Manley

K, Garbett R (eds.) Practice Development in Nursing. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

McCormack, B. and Titchen, A. 2006. Critical creativity: melding, exploding, blending. Educational Action Research: An international journal, 14(2):239‑266.

McLaren, P. and Leonard, P. 2001. Paulo Friere: a critical encounter. Routledge: London

Pierce, V., Cheesebrow, D and Braun, L.M. 2000. ‘Facilitator Competencies’. Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal,

2(2):24–31.

Reason, P., and. Bradbury, H. 2001. Handbook of Action Research.

London: Sage.

Titchen, A. and Manley, M. 2006. Spiralling towards transformational action research: philosophical and practical journeys.

Chapter 6

In Higgs, J, Titchen A, Byrne Armstrong, and Horsfall D (Eds) Being Critical and Creative in Qualitative Research) Hampden: Sydney.

Wilson, V., Hardy, S., and Brown, B. 2008.

An exploration of Practice Development Evaluation: Unearthing Praxis. In Manley, K., McCormack,

B., Wilson, V. (Eds.). International Practice Development in Nursing and Healthcare. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Wilson, H.S. and Hutchinson, S.A. 1991. Triangulation of qualitative methods: Heideggarian Hermeneutics and Ground theory. Qualitative

Health Research, 1(2):263‑276

Yaffe, S.H. 1989. Drama as a teaching tool.

Educational Leadership, 46(6):29‑32.

AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF ADVANCED NURSING Volume 29 Number 2

47