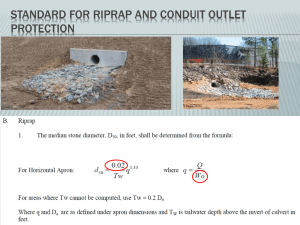

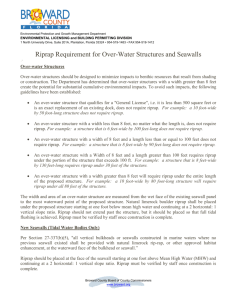

Riprap Design and Construction Guide

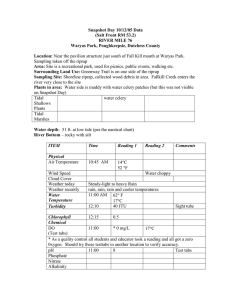

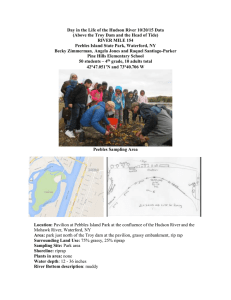

advertisement