Brief for Respondents

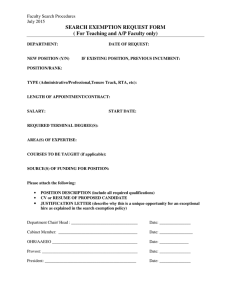

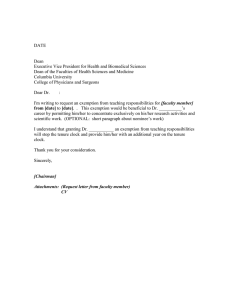

advertisement