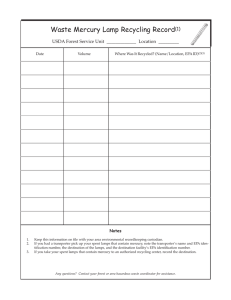

A Project for Recovering Mercury from Fluorescent Tubes from

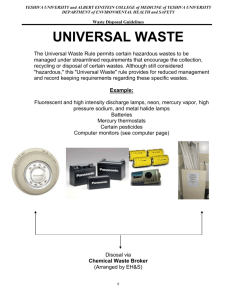

advertisement