Assessment Handbook

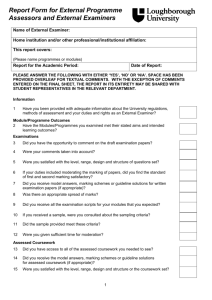

advertisement