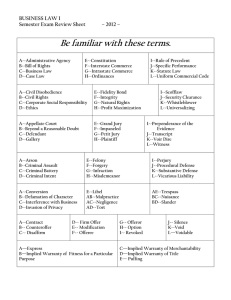

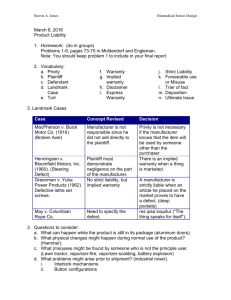

Products Warranty Law in Florida -

advertisement