applying nuisance law to internet obscenity

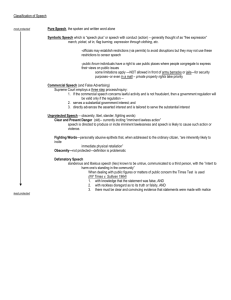

advertisement