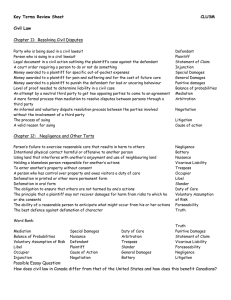

VINDICATING REPUTATION: AN ALTERNATIVE TO DAMAGES AS

advertisement