Connect

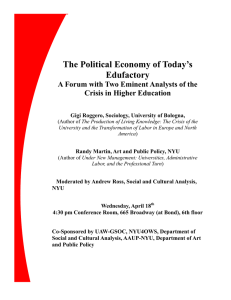

advertisement