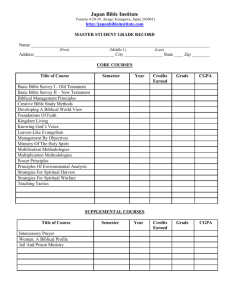

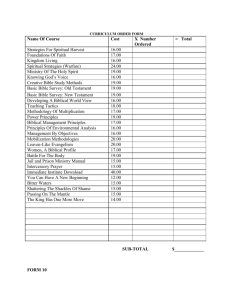

Faculty Guide - USA / Canada Region

advertisement