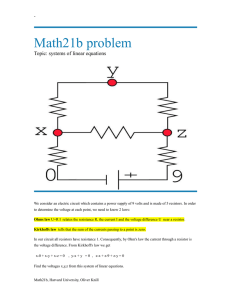

Lecture 3 - Batteries, conductors and resistors

advertisement

Batteries, conductors and resistors Lecture 3 1 How do we generate electric fields – where does the energy come from? The e.m.f. generator uses some physical principle to create an excess of electrons at one terminal and a deficit at the other. This requires energy conductor + terminal (electron deficit) e.m.f. generator + electric field energy Electrical conductors transfer the potential difference to the device (more later …!) potential difference - terminal (electron excess) When electrons move in the device electrons flow from the negative terminal to the positive terminal. Energy has been transferred from the e.m.f. generator to the K.E. of electrons Lecture 3 2 1 How can we generate e.m.f.? : 1 • Dynamo, generator – Rotary energy from a petrol engine, turbine etc. moves a conductor in a magnetic field – Mains power – we can use a POWER SUPPLY to create the e.m.f. we need • Solar cells – Ultraviolet photons from the sun create electrons directly in silicon • Thermo-electric generator – Temperature difference between junctions of different metals generates electron excess Lecture 3 3 How can we generate e.m.f.? : 2 • Fuel cell – Recombining H2 and O2 to make water releases extra electrons (energy is needed to separate H2 and O2 in the first place) • Chemical battery – Chemical reactions transfer electrons Lecture 3 4 2 Batteries • Store a fixed amount of charge (in the form of chemical energy) – So they run down • Cannot supply an unlimited current (more later) A battery with a stored charge Q can supply a current I for how long? Lecture 3 5 The ideal battery: 1 Voltage source • We will see that (for physicists!) it does not matter exactly how the e.m.f. is generated • We will represent our e.m.f. generator as an ideal battery – E.m.f. is constant independent of the current supplied – Capable of supplying any current indefinitely Circuit symbol Lecture 3 6 3 The ideal battery: 2 Current source • A device which provides a constant current INDEPENDENT OF THE VOLTAGE REQUIRED TO DO THIS Circuit symbol Lecture 3 7 Things you can’t do with ideal sources V1 V2 I1 Connect voltage sources in PARALLEL I2 Connect current sources in SERIES Lecture 3 8 4 Electrons in conductors:1 Two states of the outer electrons 1. Valence electrons These are responsible for holding the metal together – very tightly bound to the atoms 2. Conduction electrons “Left over” from chemical bonds Loosely bound to atoms and can drift through the lattice Lecture 3 9 Electrons in metals:2 • Drifting electrons have many collisions. • Electrons do not accelerate but reach a constant average “drift” velocity proportional to the applied field Electron velocity Free electron Electron in metal v = μE where μ is the electron mobility in the metal (units m2 V-1 s-1) Average velocity time Mobility depends on the chemical and physical form of the material and on temperature Lecture 3 10 5 Resistance Now we can calculate the current that passes through a block of material if you apply a potential difference across it Area A v Electrons / second: dn n= dt dn n= dt E ne A μ E ne A μV l Charge / sec (= current) l V i = ne μ e ⋅ A ⋅V l This is OHM’S LAW: Current is proportional to applied voltage Lecture 3 11 Georg Simon Ohm (1789 – 1854) Discovered Ohm’s law in 1829 (experimentally) at the University of Cologne. The Prussian Minister of Science thundered that “… any professor who preaches such heresy is unworthy to teach science!”. Ohm resigned his professorship, went into exile and eventually settled in Bavaria Lecture 3 12 6 Resistance and Resistivity i = ne μ e ⋅ A ⋅V l V w here R ρl and R= A 1 ρ = ne e μ i= R is a property of the conductor called RESISTANCE [Symbol in equations r, R. Units OHMS, symbol Ω] Resistance depends on the shape of the conductor (cross section area, A, length, l) and the properties of the material, ρ ρ is the RESISTIVITY of the material [units OHM.METRE, Ω m] V Ohms law again: volts = amps x ohms I Lecture 3 R 13 Calculating resistance Material Resistivity (ohm.m) Silver 1.59 x 10-8 Copper 1.68 x 10-8 Aluminium 2.69 x 10-8 Iron 9.71 x 10-8 Platinum 10.6 x 10-8 Nichrome* Carbon (graphite) Glass Rubber Quartz 1.0 x 10-7 3 – 60 x 10-5 1 – 10000 x 109 1 – 100 x 1013 7.5 x 1017 A R= ρl l A Example: resistance of 1 m. of 1mm diameter Pt wire: A = π r 2 = π (0.5 × 10−3 ) 2 = 7.85 × 10−7 m 2 R= ρl A = 10.6 × 10−8 × 1.0 = 0.135 Ω 7.85 × 10−7 *Nichrome – an alloy of Ni, Fe and Cr used for making resistor wire Lecture 3 14 7 Resistors R Components designed to have a well defined value of resistance are called RESISTORS These can be made of carbon, metal film or metal wire R Circuit symbols The values of small resistors are often indicated by coloured rings (the colour code). http://www.dannyg.com/examples/res2/resistor.htm has a nice graphical calculator Lecture 3 15 Connectors, wires •We will assume that all the components we use are connected together by ideal conductors of ZERO resistance (so we can ignore them – not always true in real life!) • Real connectors are usually copper wire (low resistivity, comparatively cheap) or copper foil printed in a pattern onto an insulating sheet (printed circuit board, PCB) Lecture 3 16 8 Energy in resistors Each time an electron in a conductor collides with another electron in the material, it loses kinetic energy. This energy is eventually transferred to the lattice – HEAT! I The power dissipated in a resistor is equal to the energy drawn from the power source: W = VI watts watts = volts x amps V Conservation of energy: In any circuit the power dissipated in the resistors is ALWAYS equal to the power drawn from the Lecture 3 batteries 17 Summary of formulae so far … Q = It (for constant current) V = IR; I = V / R; R = V / I (Ohm's law) P = IV (Power in a resistor) P = I 2R P =V2 / R Lecture 3 18 9 Measuring devices I A An AMMETER is inserted into a circuit to measure current. Ideal ammeter has ZERO RESISTANCE (introduces no voltage drop) V V A VOLTMETER is used to measure the potential difference across a component. An ideal voltmeter has INFINITE RESISTANCE (draws no current) Lecture 3 19 I-V curves V V I A X We can learn a lot about a component by plotting its I-V curve I ideal resistor (low R) ideal resistor (high R) I-V curve is LINEAR (only two points required) I REAL resistor: R increases when resistor gets hot V V Lecture 3 NON-linear I-V curve – several points required 20 10 I-V curves - active and passive I 2 1 VI< 0 VI > 0 V VI > 0 VI< 0 3 4 In quadrants 1 and 3: • VI > 0 • Current flowing in the same direction as applied voltage • Energy is dissipated in the component • Passive (e.g. resistor) In quadrants 2 and 4: • VI < 0 • Current flowing against the applied voltage • Energy is supplied by the component • Active (e.g. battery or current source) Lecture 3 21 I-V curves - Sources I V I V Voltage source (battery) • Voltage is constant independent of current • When current has the same sign as voltage, battery is absorbing energy Current source • Current is constant independent of voltage • When voltage has the same sign as current, source is absorbing energy Lecture 3 22 11