PHYS 536 DC Circuits Introduction Voltage Source

advertisement

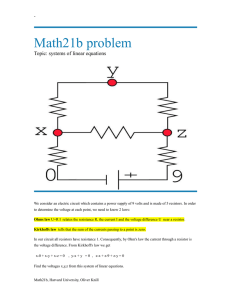

PHYS 536 DC Circuits Introduction The measurements in this experiment are simple, but the concepts illustrated are fundamental. Proper understanding of these concepts is essential for later work. A summary of the concepts and equations that are needed for this particular experiment is presented herein. Refer to Sections 1,2,3, and 7 in the General Instructions for Laboratory, hereafter referred to as GIL, for additional background information. Voltage Source Figure 1: Voltage Source diagram A perfect voltage source provides constant voltage regardless of how much current is drawn; this is not the case for real sources. The source voltage, VL , decreases as the source current, IL , increases. Using Kirchoff’s loop rule, the voltage across the load can be expressed as VL = V0 − IL r0 (1) V0 is the voltage of the source when there is no external lead, i.e. IL = 0, and r0 is the equivalent resistance of the voltage source. Recalling that eq. 1 can be rewritten as VL = V0 RL r0 + RL 1 (2) Figure 2: Current source diagram Current Source A perfect current source provides constant current, regardless of the voltage, VL , across it. However, the current, IL , from a real source is slightly dependent on the voltage, VL , across the source. Using Kirchoff’s branch rule the current through the load can be written as IL = I0 − VL r0 (3) where I0 is the source current when VL is zero. Combining Resistors The equivalent resistance of a series of n resistors is given by Req = n Ri (4) i The equivalent resistance of a n resistors in parallel is given by n 1 1 = Req Ri i (5) Voltage Dividers The voltage, VL , across several series resistors is distributed proportionally according to the size of each resistor. Referring to Fig. 3, Kirchoff’s loop rule states that 2 Figure 3: Voltage divider V0 = V1 + V2 + V3 (6) The current through the loop is given by I0 = V0 R1 + R2 + R3 (7) The voltage across resistor j, Vj , is Vj = V0 Rj R1 + R2 + R3 Current Dividers Figure 4: Current divider 3 (8) The current emanating from the voltage source is given by I0 = V0 Req (9) Where 1 1 1 1 = + + Req R1 R2 R3 The current flowing through resistor Rj is Ij = V0 I0 Req = Rj Rj If, for instance, there are only two resistors, the currents are given by I1 = I0 R2 R1 + R2 (10) I2 = I0 R1 R1 + R2 (11) and The current flowing through two parallel resistors is inversely proportional to the resistance. Notice that I1 is proportional to R2 , not R1 , and vice versa. Thevenin’s Theorem Any linear circuit can be represented by an equivalent voltage source, VT h , and resistance, rT h , in series. VT h is the voltage with no external load. RT h is the combination of resistors obtained with inactive sources: short circuit for voltage source and open circuit for current source. Norton’s Theorem Any linear circuit can be represented by an equivalent current source, IN , and a resistance, rN , in parallel. IN is the current that flows through a short circuit, which replaces the load. rN is the same for Thevenin’s and Norton’s theorem. 4 1 Effective Resistance of a Voltage Source Figure 5: Effective resistance circuit A D-cell will be used to demonstrate the general principle that the voltage from a source decreases when it delivers current to a load. The bread board provides a convenient place to add resistors for the measurement. Connect the D-cell and the digital meter to two different power bars on the bread board. Load resistors, RL , will be inserted to change the current, Is , supplied by the battery. The load should be connected into terminals only as long as necessary to measure Vs . If too much charge is drawn from the battery, the no load voltage will change. 1. Assuming a battery voltage of 1.5 V, i.e. V0 = 1.5 V, and an internal resistance, r0 , of 0.5 Ω , calculate Vs for Is = 0, 0.1, and 1 A. Include the results of these calculations in your lab report. 2. Measure V0 of a D-cell battery. 3. Set up the circuit as shown is Fig. 5. Measure Vs for RL = 10 Ω, 4.7 Ω, 2.2 Ω, and 1 Ω. Recheck V0 at the end. If the value has changed calculate the mean. 4. Calculate the current through the load using the formula Is = Vs RL (12) 5. Plot Vs (vertical) versus Is and determine r0 from the slope. This r0 could be used to calculate Vs for any RL . Include in your lab report example calculations for RL = 10 Ω and RL = 1 Ω . For both the calculations and measurements enter your data into a spreadsheet program and plot the 5 data. How close are the data to linear? Use the spreadsheet program to fit a line to the data. How good is the fit? Include these results in your lab report. 2 Voltage Divider Figure 6: Voltage Divider 1. Set up the circuit shown in Fig. 6 on the bread board. Connect the 12 V output of the DC power supply to the two different power bars. Use resistance values shown in the figure. 2. Measure the voltage across each resistor. Use both meters, noting differences in your lab report. The meters read the voltage on the input lead relative to the “common” lead. The common side of the meter may be labeled as“low” or “-”. In this circuit the voltage of A relative to D should be positive and D relative to A should be negative. Try several variations until you understand the polarity conventions of the meters. 3. Do the measurements made in this part of the experiment confirm Kirchoff’s first rule? Repeat the measurements several times, noting all voltages. Do the measurements always agree? Based on these measurements, what is the reproducibility of the voltmeters? 3 Combining Resistors 1. Consider the circuit shown in Fig. 7. Using equivalent resistances, and Kirchoff’s rules if needed, predict VAB , VAC , I1 , and I2 . 2. Set up the circuit in Fig. 7 on the bread board and connect it to the power supply. Do not insert the meter probes into circuit sockets because the probe tips damage the sockets, use wires instead. Measure VAB , VAC , 6 Figure 7: Combining Resistors I1 , and I2 . Compare these measurements with your calculations; make a table comparing the two. 4 Thevinin’s Theorem Figure 8: Thevinin’s Theorem 1. Set up the circuit shown in Fig. 8 and measure VAB with R = 2 kΩ, 9.1 kΩ, and without R (open circuit). 2. Comment on the results in light of Thevenin’s theorem. 3. Calculate the Thevenin equivalent voltage and resistance, and draw the Thevenin equivalent circuit. 7 5 Accuracy of Voltmeters Figure 9: Voltmeter circuit An ideal voltmeter has infinite resistance. Real voltmeters, however, have a large, finite resistance, typically of the order of megaohms. In this section, you will measure the resistance of your multimeter operating in voltmeter mode. 1. Build the circuit shown in Fig. 9 using a 10 MΩ resistor for R1 and a voltage of 15 V. 2. Place the multimeter in voltmeter mode. 3. Record the voltage measured by the voltmeter. 4. The voltmeter in this configuration can be thought of as a resistor with resistance equal to the resistance of the multimeter in parallel with an ideal voltmeter with infinite resistance. What is the multimeter’s resistance? 6 Transistor with Fixed Resistance 1. Build the circuit shown in Fig. 10 using the provided MPF 102 transistor which already has resistor R1 = 1 kΩ soldered across two of the leads of the transistor. For this part and the next part, be sure to use the more precise Fluke multimeter. 2. With the multimeter, measure the current flowing with the power supply set to 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 V. 3. Plot the current as a function of voltage. 4. Did the current change much when you changed the voltage applied? 8 Figure 10: Transistor circuit with fixed resistance 7 Transistor with Fixed Voltage 1. Build the circuit shown in Fig. 11, again using the provided transistor. 2. Set the voltage at 15 V. 3. Measure the current for R2 = 1 kΩ, 2 kΩ, and 10 kΩ. 4. Plot the current as a function of resistance. 5. Does the current change much despite the large differences in the values of the resistors used? 6. What do the results of this section and the previous section imply about the nature of the transistor? 9 Figure 11: Transistor circuit with variable resistance 10